War may seem to favor those with a clear head and steady hand, but strategy is only half the battle. A sense of invincibility must be achieved in the combatants, at least until technology allows all the killing machines to be actual machines.

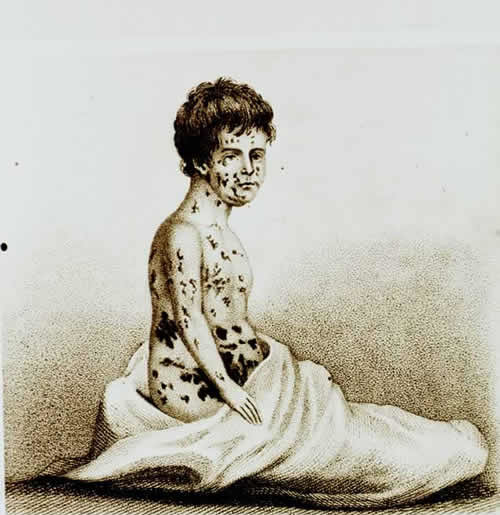

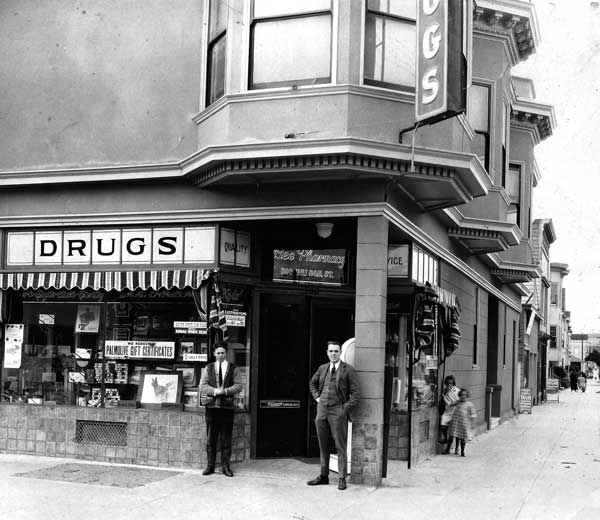

Human beings are no angels, but genocide and beheading, for instance, are not, thankfully, our default mode. Such heinous courses can be decided on by sober if sinister minds but their commission sometimes requires moods altered either by hysteria and brainwashing or, more simply, pharmaceuticals. The Nazis favored crystal meth and ISIS Captagon, these forms of amphetamine not only helpful with focus and energy but also able to disappear inhibitions.

Crimes against humanity can certainly occur without speed, but oftentimes you’ll find a pervasive drug culture in close proximity to such atrocities. It’s not the source of evil but a way to lubricate the war machine.

An excerpt from “Don’t Fight Sober,” Mike Jay’s London Review of Books piece on new volumes on the topic by Łukasz Kamieński and Norman Ohler:

The unreliable narratives that always build up around illicit drugs are compounded by the fog of war. Exaggeration, doubletalk and disinformation bend reality into mythic shapes. The image of the Captagon-crazed jihadi is reminiscent of the Assassins, whose story was imported to Europe by Marco Polo: they were said to have been brainwashed with a dose of hashish and persuaded by their fanatical leader that suicide missions would be rewarded with an eternity in paradise. Recent scholarship has established that ‘assassins’ (or ‘hashishin’) was a pejorative term applied to them by their enemies: in fact they were a strictly ascetic order whose adherents abstained from all drugs including alcohol. The appeal of the myth is obvious: if the drugs made them do it, their motives require no further investigation. Asked after the Bataclan attacks whether the killers had been on drugs, Montasser Alde’emeh, a Belgian-Palestinian expert on radicalisation, turned the question succinctly on its head: ‘Unfortunately, they don’t need it. Their ideology is their Captagon!’

In Shooting Up, a historical survey of drugs in warfare that grew out of his research into future military applications of biotechnology, Łukasz Kamieński lists some of the obstacles to getting the facts straight. State authorities tend to cloak drug use in secrecy, for tactical advantage and because it frequently conflicts with civilian norms and laws. Conversely it can be exaggerated to strike fear into the enemy, or the enemy’s success and morale can be imputed to it. When drugs are illegal, as they often are in modern irregular warfare, trafficking or consumption is routinely denied. The negative consequences of drug use are covered up or explained away as the result of injury or trauma, and longer-term sequels are buried within the complex of post-traumatic disorders. Soldiers aren’t fully informed of the properties and potency of the drugs they’re consuming. Different perceptions of their role circulate even among participants fighting side by side.

Kamieński confines the use of alcohol in war to his prologue and wisely so, or the rest of the book would risk becoming a footnote to it. A historical sweep from the Battle of Hastings to Waterloo or ancient Greece to Vietnam suggests that war has rarely been fought sober. This is unsurprising in view of the many different functions alcohol performs. It has always been an indispensable battlefield medicine and is still pressed into service today as antiseptic, analgesic, anaesthetic and post-trauma stimulant. It has a central role in boosting morale and small-group bonding; it can facilitate the private management of stress and injury; and it makes sleep possible where noise, discomfort or stress would otherwise prevent it. After the fighting is done, it becomes an aid to relaxation and recovery.

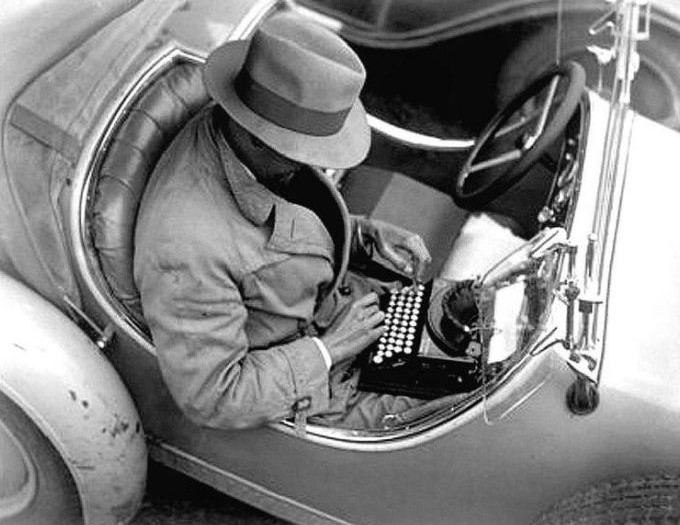

All these functions are subsidiary to its combat role and Kamieński’s particular interest, the extent to which drugs can transform soldiers into superhuman fighting machines.•