I read Sean Penn’s “El Chapo Speaks” at the beginning of 2016, and spent the rest of the year trying to absorb as many great articles as I could to erase from my mind the awful reporting and prose. “Espinoza is the owl who flies among falcons,” wrote the actor-director-poetaster. Yes, Sean, okay, but go fuck yourself.

The following 50 articles made me feel pretty good again. In time, I myself once more began to fly among the falcons.

Congratulations to all the wonderful writers who made the list. My apologies for not reading more small journals and sites, but the time and money of any one person, myself included, is limited.

1) “Latina Hotel Workers Harness Force of Labor and of Politics in Las Vegas” and 2) “A Fighter’s Hour of Need” (Dan Barry, New York Times).

As good as any newspaper writer–or whatever you call such people now–Barry reports and composes like a dream. The first piece has as good a kicker as anyone could come up with–even if life subsequently kicked back in a shocking way–and the second is a heartbreaker about the immediate aftermath of a 2013 boxing match in which Magomed Abdusalamov suffered severe brain damage.

Even when Barry shares a byline, I still feel sure I can pick out his sentences, so flawless and inviting they are. One example of that would be…

3) “An Alt-Right Makeover Shrouds the Swastikas” by Barry, Serge F. Kovaleski, Julie Turkewitz and Joseph Goldstein.

An angle used to dismiss the idea that the Make America Great White Again message resonated with a surprising, depressing number of citizens has been to point out that some Trump supporters also voted for Obama. That argument seems simplistic. Some bigots aren’t so far gone that they can’t vote for a person of a race they dislike if they feel it’s in their best interests financially or otherwise. That is to say, some racially prejudiced whites voted for President Obama. Trump appealed to them to find their worst selves. Many did.

Likewise the Trump campaign emboldened far worse elements, including white nationalists and separatists and anti-Semites. Thinking they’d been perhaps permanently marginalized, these hate groups are now updating their “brand,” hiding yesterday’s swastikas and burning crosses and other “bad optics,” and referring to themselves not as neo-Nazis but by more vaguely appealing monikers like “European-American advocates.” It’s the same monster wrapped in a different robe, the mainstreaming of malevolence, and they won’t again be easily relegated to the fringe regardless of Trump’s fate.

This group of NYT journalists explores a beast awakened and energized by Trump’s ugly campaign. It’s a great piece, though we should all probably stop calling these groups by their preferred KKK 2.0 alias of “alt-right.”

4) “No, Trump, We Can’t Just Get Along” (Charles Blow, New York Times)

In the hours after America elected, if barely, a Ku Klux Kardashian, most pundits and talk-show hosts encouraged all to support this demagogue, as if we could readily forget that he was a racist troll who demanded the first African-American President show his birth certificate, a deadbeat billionaire who didn’t pay taxes or many of his contracted workers, a draft-dodger who mocked our POWs while praising Putin, a sexual predator who boasted about his assaults, a xenophobe who blamed Mexicans and Muslims, a bigot who had a long history of targeting African-Americans with the zeal of a one-man lynching bee. In a most passionate and lucid shot across the bow, Blow said “no way,” penning an instant classic, speaking for many among the disenfranchised majority.

5) “Lunch with the FT: Burning Man’s Larry Harvey“ (Tim Bradshaw, Financial Times)

If self-appointed Libertarian overlord Grover Norquist, a Harvard graduate with a 13-year-old’s understanding of government and economics, ever had his policy preferences enacted fully, it would lead to worse lifestyles and shorter lifespans for the majority of Americans. In fact, we now get to see many of his idiotic ideas played out in real-life experiments. He’s so eager to Brownback the whole country he’s convinced himself, despite being married to a Muslim woman, there’s conservative bona fides in Trump’s Mussolini-esque stylings and suspicious math.

In 2014, Norquist made his way to the government-less wonderland known as Burning Man, free finally from those bullying U.S. regulations, the absence of which allows Chinese business titans to breathe more freely, if not literally. Norquist’s belief that the short-term settlement in the Nevada desert is representative of what the nation could be every day is no less silly than considering Spring Break a template for successful marriage. He was quote as saying: “Burning Man is a refutation of the argument that the state has a place in nature.” Holy fuck, who passed him the peyote?

In his interview piece, Bradshaw broke bread in San Francisco with Harvey, co-founder of Burning Man and its current “Chief Philosophic Officer,” who speaks fondly of rent control and the Bernie-led leftward shift of the Democratic Party. Norquist would not approve, even if Harvey is a contradictory character, insisting he has a “conservative sensibility” and lamenting the way many involved in social justice fixate on self-esteem.

6) “The World Wide Cage” and 7) “Humans Have Long Wished to Fly Like Birds: Maybe We Shall” (Nicholas Carr, Aeon)

One of the best critics of our technological society keeps getting better.

The former piece is the introduction to Carr’s essay collection Utopia Is Creepy. The writer argues (powerfully) that we’ve defined “progress as essentially technological,” even though the Digital Age quickly became corrupted by commercial interests, and the initial thrill of the Internet faded as it became “civilized” in the most derogatory, Twain-ish use of that word. To Carr, the something gained (access to an avalanche of information) is overwhelmed by what’s lost (withdrawal from reality). The critic applies John Kenneth Galbraith’s term “innocent fraud” to the Silicon Valley marketing of techno-utopianism.

You could extrapolate this thinking to much of our contemporary culture: binge-watching endless content, Pokémon Go, Comic-Con, fake Reality TV shows, reality-altering cable news, etc. Carr suggests we use the tools of Silicon Valley while refusing the ethos. Perhaps that’s possible, but I doubt you can separate such things.

The latter is a passage about biotechnology which wonders if science will soon move too fast not only for legislation but for ethics as well. The “philosophy is dead” assertion that’s persistently batted around in scientific circles drives me bonkers because we dearly need consideration about our likely commandeering of evolution. Carr doesn’t make that argument but instead rightly wonders if ethics is likely to be more than a “sideshow” when garages aren’t used to just hatch computer hardware or search engines but greatly altered or even new life forms. The tools will be cheap, the “creativity” decentralized, the “products” attractive. As Freeman Dyson wrote nearly a decade ago: “These games will be messy and possibly dangerous.”

8) “Calum Chace: Ask Me Anything” (Chace, Reddit)

The writer, an all-around interesting thinker, conducted an AMA based on his book, The Economic Singularity, which envisions a future–and not such a far-flung one–when human labor is a thing of the past. It’s certainly possible since constantly improving technology could make fleets of cars driverless and factories workerless. In fact, there’s no reason why they can’t also be ownerless.

What happens then? How do we reconcile a free-market society with an automated one? In the long run, it could be a great victory for humanity, but getting from here to there will be bumpy.

9) “England’s Post-Imperial Stress Disorder” (Andrew Brown, Boston Globe)

Not being intimately familiar with the nuances of the U.K.’s politics and culture, I’m wary of assigning support for Brexit to ugly nativist tendencies, but it does seem a self-harming act provoked by the growing pains of globalism. It’s not nearly as dumb a move as a President Trump, for instance, but some of the same forces are at play, particularly when it comes to the pro-Brexit, anti-immigration UKIP party.

It’s not shocking that Britain and the U.S. are trying to dodge the arrival of a new day and greater competition, a time when empires can’t merely strike back at will. We’re richer now, we have better things, but the distribution is very uneven and we feel poor inside. For some, maybe a surprising number, blame must be assigned to the “others.” As Randy Newman sang: “The end of an empire is messy at best.”

10) “My President Was Black” (Ta-Nahesi Coates, The Atlantic)

It wasn’t the color of President Obama’s suit that so bothered his critics but the color of his skin. Sure, Bill Clinton was impeached and John Kerry swiftboated, but there was something so deeply disqualifying about the antagonism that faced 44, something beyond mere partisanship, which boiled over into Birtherism, interruptions during the State of the Union, denial of his Christian faith and vicious insults hurled at his gorgeous wife.

The old adage that black people have to be twice as good at a job as white people proved to be mathematically refutable: The Obamas were a million times better, and it wasn’t nearly enough for their detractors. When Obama even mildly suggested that institutional racism still existed, something he rarely did, he was labeled a “jerk” by prominent Republicans. Worse yet, his most overtly bigoted tormentor will succeed him in the White House.

That raises an obvious question: If the perfect son isn’t good enough, then what kind of chance do his siblings have?

In a towering essay, Coates reflects on Obama’s history and the “fitful spasmodic years” of his White House tenure, which had pluses and minuses but were a gravity-defying time of true accomplishment which will never happen the same way again. In addition to macro ideas about race and identity, Coates’ writing on the Justice Department under this Administration is of particular importance.

11) “The Problem With Obama’s Faith in White America“ (Tressie McMillan Cottom, The Atlantic)

Hope is usually audacious but sometimes misplaced.

Without that feeling of expectation in a country founded on white supremacy that has never erased institutional racism, Barack Hussein Obama would certainly have never been elected President of the United States, not once, let alone twice. But his hope has also served as an escape hatch for white Americans who wanted to not only ignore the past but also the present. By stressing the best in us, Obama overlooked the worst of us, and that worst has never gone away.

It’s doubtful he behaved this way merely due to political opportunism: Obama seems a true believer in America and the ideals it espouses but has never lived up to. I love him and Michelle and think they’re wonderful people, but the nation has never been as good as they are, and even on a good day I’m unsure we even aspire to be. A painfully true Atlantic essay by Cottom meditates on these ideas.

12) “We’re Coming Close to the Point Where We Can Create People Who Are Superior to Others” (Hannah Devlin, The Guardian)

Devlin interviews novelist Kazuo Ishiguro, who wonders if liberal democracy will be doomed by a new type of wealth inequality, the biological kind, in which gene editing and other tools make enhancement and improved health available only to the haves. Ishiguro isn’t a fatalist on the topic, encouraging more public engagement.

Some believe exorbitantly priced technologies created for the moneyed few will rapidly decrease in price and make their way inside everyone’s pockets (and bodies and brains), the same distribution path blazed by consumer electronics. That’s possible but certainly not definite. Of course, as the chilling political winds of 2016 have demonstrated, liberal democracy may be too fragile to even survive to that point.

13) “The Privacy Wars Are About to Get a Whole Lot Worse” (Cory Doctorow, Locus Magazine)

Read the fine print. That’s always been good advice, but it’s never been taken seriously when it comes to the Internet, a fast-moving, seemingly ephemeral medium that doesn’t invite slowing down to contemplate. So companies attach a consent form to their sites and apps about cookies. No one reads it, and there’s no legal recourse from having your laptop or smartphone from being plundered for all your personal info. It quietly removes legal recourse from surveillance capitalism.

In an excellent piece, Doctorow explains how this oversight, which has already had serious consequences, will snake its way into every corner of our lives once the Internet of Things turns every item into a computer, cars and lamps and soda machines and TV screens. “Notice and consent is an absurd legal fiction,” he writes, acknowledging that it persists despite its ridiculous premise and invasive nature.

14) “The Green Universe: A Vision” (Freeman Dyson, New York Review of Books)

I’ve probably enjoyed Dyson’s “pure speculation” writings as much as anything I’ve read during my life, particularly the Imagined Worlds lecture and his NYRB essays and reviews. In this piece, the physicist goes far beyond his decades-old vision of an “Astrochicken” (a spacecraft that’s partly biological), conjuring a baseball-sized, biotech Noah’s Ark that can “seed” the Universe with millions of species of life. “Sometime in the next few hundred years, biotechnology will have advanced to the point where we can design and breed entire ecologies of living creatures adapted to survive in remote places away from Earth,” he writes. It’s a spectacular dream, though we may bury ourselves beneath water or ash long before it can come to fruition, especially with the threat of climate change.

15) “The Augmented Human Being: A Conversation With George Church” (Edge)

CRISPR’s surprising success has swept us into an age when it all seems possible: the manipulation of humans, animals and plants, even perhaps of extinct species. Which way forward?

The geneticist Church, who has long had visions of rejuvenated woolly mammoths and augmented humans, realizes some bristle at manipulation of the Homo sapiens germline because it calls into question all we are, but apart from metaphors, there are also very real practical concerns over the games getting messy and possibly dangerous. The good (diseases being edited out of existence, organs being tailored to transplantees, etc.) shouldn’t be dreams permanently deferred, but it is difficult to understand how bad applications will be contained. Of course, the negative will probably unfold regardless, so we owe it ourselves to pursue the positive, if carefully. Church himself is on board with a cautious approach but not one that’s unduly so.

16) “The Empty Brain” (Robert Epstein, Aeon)

Since the 16th century, the human brain has often been compared to a machine of one sort or another, with it being likened to a computer today. The idea that the brain is a machine seems true, though the part about gray matter operating in a similar way to the gadgets that currently sit atop our laps or in our palms is likely false.

In a wonderfully argumentative and provocative essay, psychologist Epstein says this reflexive labeling of human brains as information processors is a “story we tell to make sense of something we don’t actually understand.” He doesn’t think the brain is tabula rasa but asserts that it doesn’t store memories like an Apple would.

It’s a rich piece of writing full of ideas and examples, though I wish Epstein would have relied less on the word “never” (e.g., “we will never have to worry about a human mind going amok in cyberspace”), because while he’s almost certainly correct about the foreseeable future, given enough time no one knows how the machines in our heads and pockets will change.

17) “North Korea’s One-Percenters Savor Life in ‘Pyonghattan‘” (Anna Fifield, The Washington Post)

Even in Kim Jong-un’s totalitarian state there are haves and have-nots who experience wildly different lifestyles. In the midst of the politically driven arrests and murders, military parades and nuclear threats, there exists a class of super rich kids familiar with squash courts, high-end shopping and fine dining. “Pyonghattan,” it’s called, this sphere of Western-ish consumerist living, which is, of course, just a drop in the bucket when compared to the irresponsible splurges of the Rodman-wrangling “Outstanding Leader.” Still weird, though.

18) “Being Leonard Cohen’s Rabbi“ (Rabbi Mordecai Finley, Jewish Journal)

The poet of despair, who lived for a time in a monastery, spent some of his last decade discussing spirituality and more earthly matters with the Los Angeles-based rabbi, who explains how the Jewish tradition informed Cohen’s work. “We shared a common language, a common nightmare,” he writes. One remark the prophet of doom made to Finley hits especially hard with the demons awakened during this election season: “You won’t like what comes next after America.”

19) Five Books Interview: Ellen Wayland-Smith Discusses Utopias (Five Books)

In a smart Q&A, Wayland-Smith, author of Oneida, talks about a group of titles on the topic of Utopia. She surmises that attempts at such communities aren’t prevalent like they were in the 1840s or even the 1960s because most of us realize they don’t normally end well, whether we’re talking about the bitter financial and organizational failures of Fruitlands and Brook Farm or the utter madness of Jonestown. That’s true on a micro-community level, though I would argue that there have never been more people dreaming of large-scale Utopias–and corresponding dystopias–then there are right now. The visions have just grown significantly in scope.

In macro visions, Silicon Valley technologists speak today of an approaching post-scarcity society, an automated, quantified, work-free world in which all basic needs are met and drudgery has disappeared into a string of zeros and ones. These thoughts were once the talking points of those on the fringe, say, a teenage guru who believed he could levitate the Houston Astrodome, but now they (and Mars settlements, a-mortality and the computerization of every object) are on the tongues of the most important business people of our day, billionaires who hope to shape the Earth and beyond into a Shangri-La.

Perhaps much good will come from these goals, and maybe a few disasters will be enabled as well.

20) “Sam Altman’s Manifest Destiny” (Tad Friend, New Yorker)

Friend’s “Letter from California” articles in the New Yorker are probably the long-form journalism I most anticipate, because he’s so good at understanding distinct milieus and those who make them what they are, revealing the micro and macro of any situation or subject and sorting through psychological motivations that drive the behavior of individuals or groups. To put it concisely: He gets ecosystems.

The writer’s latest effort, a profile of Y Combinator President Sam Altman, a stripling yet a strongman, reveals someone who has almost no patience for or interest in most people yet wants to save the world–or something.

It’s not a hit job, as Altman really has no intent to offend or injure, but it vivisects Silicon Valley’s Venture Capital culture and the outrageous hubris of those insulated inside its wealth and privilege, the ones who nod approvingly while watching Steve Jobs use Mahatma Gandhi’s image to sell wildly marked-up electronics made by sweatshop labor, and believe they also can think different.

When envisioning the future, Altman sees perhaps a post-scarcity, automated future where a few grand a year of Universal Basic Income can buy the jobless a bare existence (certainly not the big patch of Big Sur he owns), or maybe there’ll be complete societal collapse. Either or. More or less. If the latter occurs, the VC wunderkind plans to flee the carnage by jetting to the safety of his New Zealand spread with Peter Thiel, who has a moral blind spot reminiscent of Hitler’s secretary. A grisly death seems preferable.

21) “The Secret Shame of Middle-Class Americans” (Neal Gabler, The Atlantic)

The term “middle class” was not always a nebulous one in America. It meant that you had arrived on solid ground and only the worst luck or behavior was likely to shake the earth beneath your feet. That’s become less and less true for four decades, as a number of factors (technology, globalization, tax codes, the decline of unions, the 2008 economic collapse, etc.) have conspired to hollow out this hallowed ground. You can’t arrive someplace that barely exists.

Middle class is now what you think you would be if you had any money. George Carlin’s great line that “the reason they call it the American Dream is because you have to be asleep to believe it” seems truer every day. It’s not so much a fear of falling anymore, but the fear of never getting up, at least not within the current financial arrangement. Those hardworking, decent people you see every day? They’re just as afraid as you are. They are you.

In the spirit of the great 1977 Atlantic article “The Gentle Art of Poverty” and William McPherson’s recent Hedgehog Review piece “Falling,” the excellent writer and film critic Gabler has penned an essay about his “secret shame” of being far poorer than appearances would indicate.

22) “Nate Parker and the Limits of Empathy” (Roxane Gay, The New York Times)

We have to separate the art and the artist or we’ll end up without a culture, but it’s not always so easy to do. There was likely no more creative person who ever walked the Earth than David Bowie, whose death kicked off an awful 2016, yet the guy did have sex with children. And Pablo Picasso beat women, Louis-Ferdinand Céline was an anti-Semite, Anne Sexton molested her daughter and so on. In Gay’s smart, humane op-ed, she looks at the controversy surrounding Birth of a Nation writer-director Parker, realizing she can’t compartmentalize her feelings about creators and creations. Agree with her or not, but it’s certainly a far more suitable response than Stephen Galloway’s shockingly amoral Hollywood Reporter piece on the firestorm.

23) “The Case Against Reality“ (Amanda Gefter, The Atlantic)

A world in which Virtual Reality is in wide use would present a different way to see things, but what if reality is already not what we think it is? It’s usually accepted that we don’t all see things exactly the same way–not just metaphorically–and that our individual interpretation of stimuli is more a rough cut than an exact science. It’s a guesstimate. But things may be even murkier than we believe. Gefter interviews cognitive scientist Donald D. Hoffman who thinks our perception isn’t even a reliable simulacra, that what we take in is nothing like what actually is. It requires just a few minutes to read and will provoke hours of thought.

24) “Autocracy: Rules for Survival” (Masha Gessen, New York Review of Books)

For many of us the idea of a tyrant in the White House is unthinkable, but for some that’s all they can think about. These aren’t genuinely struggling folks in the Rust Belt whose dreams have been foreclosed on by the death rattle of the Industrial Age and made a terrible decision that will only deepen their wounds, but a large number of citizens with fairly secure lifestyles who want to unleash their fury on a world not entirely their own anymore.

I’ve often wondered how Nazi Germany was possible, and I think this election has finally provided me with the answer. There has to be pervasive prejudice, sure, and it helps if there is a financially desperate populace, but I also think it’s the large-scale revenge of mediocrity, of people wanting to establish an order where might, not merit, will rule.

Gessen addresses the spooky parallels between Russia and this new U.S. as we begin what looks to be a Trump-Putin bromance. Her advice to those wondering if they’re being too paranoid about what may now occur: “Believe the autocrat.”

25) “The Future of Privacy” (William Gibson, New York Times)

What surprises me most about the new abnormal isn’t that surveillance has entered our lives but that we’ve invited it in.

For a coupon code or a “friend,” we’re willing to surrender privacy to a corporate state that wants to engage us, know us, follow us, all to better commodify us. In fact, we feel sort of left out if no one is watching.

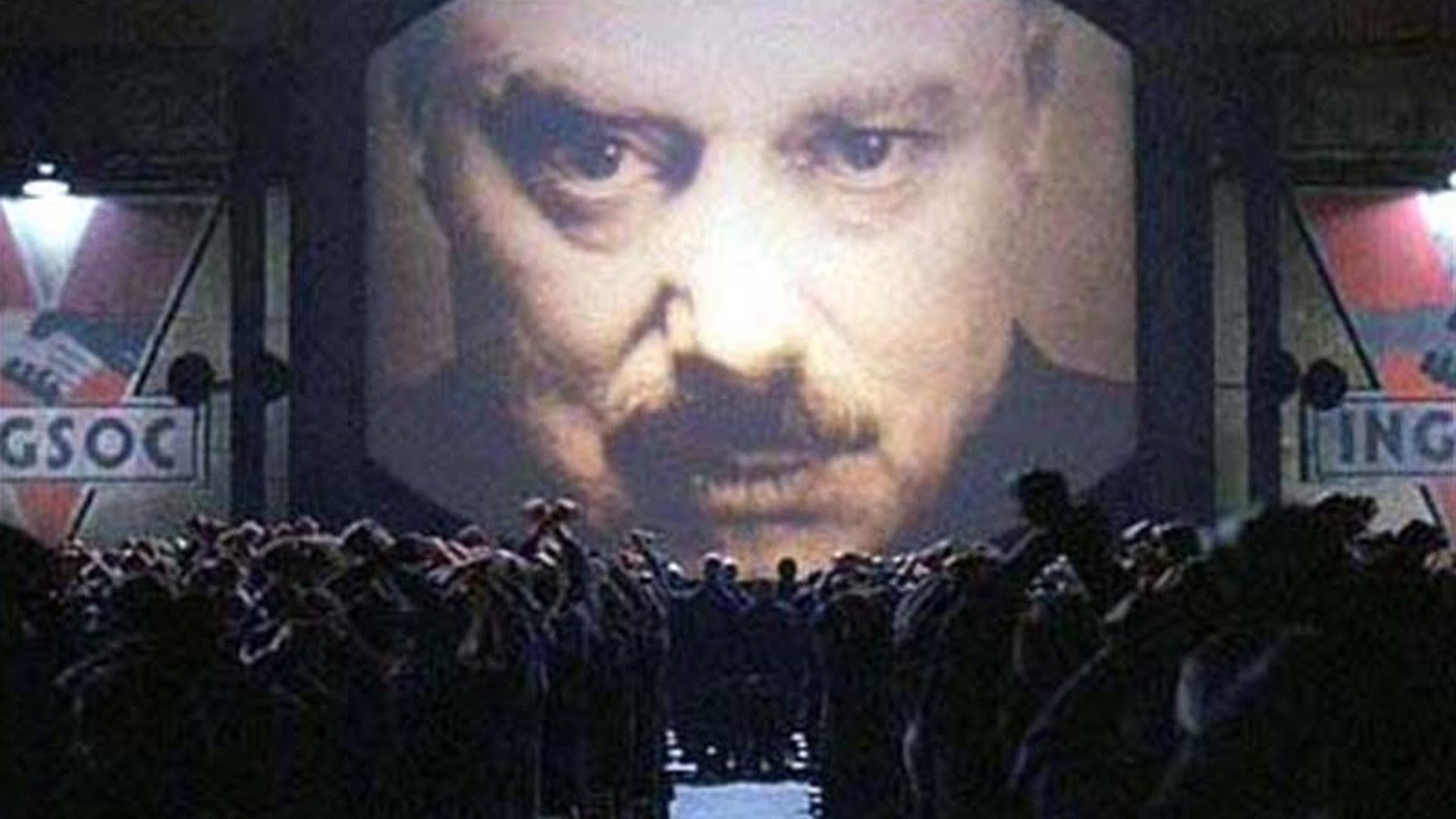

It may be that in a scary world we want a brother looking after us even if it’s Big Brother, so we’ve entered into an era of likes and leaks, one that will only grow more profoundly challenging when the Internet of Things becomes the thing.

In a wonderful essay, Gibson considers privacy, history and encryption, those thorny, interrelated topics.

26) “Why You Should Believe in the Digital Afterlife” (Michael Graziano, The Atlantic)

When Russian oligarch Dmitry Itskov vows that by 2045 we’ll be able to upload our consciousness into a computer and achieve a sort of immortality, I’m perplexed. Think about the unlikelihood: It’s not a promise to just create a general, computational brain–difficult enough–but to precisely simulate particular human minds. That ups the ante by a whole lot. While it seems theoretically possible, this process may take awhile.

The Princeton neuroscientist Graziano plots the steps required to encase human consciousness, to create a second life that sounds a bit like Second Life. He acknowledges opinions will differ over whether we’ve generated “another you” or some unsatisfactory simulacrum, a mere copy of an original. Graziano’s clearly excited, though, by the possibility that “biological life [may become] more like a larval stage.”

27) “Big Data, Google and the End of Free Will” (Yuval Noah Harari, The Financial Times)

First we slide machines into our pockets, and then we slide into theirs.

As long as humans have roamed the Earth, we’ve been part of a biological organism larger than ourselves. At first, we were barely connected parts, but gradually we became a Global Village. In order for that connectivity to become possible, the bio-organism gave way to a technological machine. As we stand now, we’re moving ourselves deeper and deeper into a computer, one with no OFF switch. We’ll be counted, whether we like it or not. Some of that will be great, and some not.

The Israeli historian examines this new normal, one that’s occurred without close study of what it will mean for the cogs in the machine–us. As he writes, “humanism is now facing an existential challenge and the idea of ‘free will’ is under threat.”

28) “How Howard Stern Owned Donald Trump” (Virginia Heffernan, Politico Magazine)

Whether it’s Howard Stern or that other shock jock Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump’s deep-seated need for praise has made him a mark for those who know how to push his buttons. In the 1990s, when the hideous hotelier was at a career nadir, he was a veritable Wack Packer, dropping by the Stern show to cruelly evaluate women and engage in all sorts of locker-room banter. Trump has dismissed these un-Presidential comments as “entertainment,” but his vulgarity off-air is likewise well-documented. He wasn’t out of his element when with the King of All Media but squarely in it. And it wasn’t just two decades ago. Up until 2014, Trump was still playing right along, allowing himself to be flattered into conversation he must have realized on some level was best avoided.

For Stern, who’s become somewhat less of an asshole as Trump has become far more of one, the joke was always that ugly men were sitting in judgement of attractive women. The future GOP nominee, however, was seemingly not aware he was a punchline. He’s a self-described teetotaler who somehow has beer goggles for himself. During this Baba Booey of an election season, Heffernan wrote knowingly of the dynamic between the two men.

29) “I’m Andrew Hessel: Ask Me Anything” (Hessel, Reddit)

If you like your human beings to come with fingers and toes, you may be disquieted by this undeniably heady AMA conducted by a futurist and a “biotechnology catalyst” at Autodesk. The researcher fields questions about a variety of flaws and illnesses plaguing people that biotech may be able to address, even eliminate. Of course, depending on your perspective, humanness itself can be seen as a failing, something to be “cured.”

30) “What If the Aliens We Are Looking For Are AI?” (Richard Hollingham, BBC Future)

If there are aliens out there, Sir Martin Rees feels fairly certain they’re conscious machines, not oxygen-hoarding humans. It’s just too inhospitable for carbon beings to travel beyond our solar system. He allows that perhaps cyborgs, a form of semi-organic post-humans, could possibly make a go of it. But that’s as close a reflection of ourselves we may be able to see in space. Hollingham explores this theory, wondering if a lack of contact can be explained by the limits we put on our search by expecting a familiar face in the final frontier.

31) “We Are Nowhere Close to the Limits of Athletic Performance” (Stephen Hsu, Nautilus)

If performance-enhancing drugs weren’t at all dangerous to the athletes using them, should they be banned?

I bet plenty of people would say they should, bowing before some notion of competitive purity which has never existed. It’s also a nod to “god-given ability,” a curious concept in an increasingly agnostic world. Why should those born with the best legs and lungs be the fastest? Why should the ones lucky enough to have the greatest gray matter at birth be our best thinkers? Why should those fortunate to initially get the healthiest organs live the longest? It doesn’t make much sense to hold back the rest of the world out of respect for a few winners of the genetics lottery.

Hsu relates how genetic engineering will supercharge athletes and the rest of us, making widely available the gifts of Usain Bolt, who gained his from hard work, sure, but also a twist of fate. In fact, extrapolating much further, he believes “speciation seems a definite possibility.”

32) “How Democracies Fall Apart” (Andrea Kendall-Taylor and Erica Frantz, Foreign Affairs)

If we are hollow men (and women), American liberty, that admittedly unevenly distributed thing, may be over after 240 years. And it could very well end not with a bang but a whimper.

Those waiting for the moment when autocracy topples the normal order of things are too late. Election Day was that time. It’s not guaranteed that the nation transforms into 1930s Europe or that we definitely descend into tyranny, but the conditions have never been more favorable in modern times for the U.S. to capitulate to autocracy. The creeps are in office, and the creeping will be a gradual process. Don’t wait for an explosion; we’re living in its wake.

Kendall-Taylor and Frantz analyze how quietly freedom can abandon us.

33) Khizr Khan’s Speech to the 2016 Democratic National Convention (Khan, DNC)

Ever since Apple’s “Think Different” ad in 1997, the one in which Steve jobs used Gandhi’s image to sell marked-up consumer electronics made by sweatshop labor, Silicon Valley business titans have been celebrated the way astronauts used to be. Jobs, who took credit for that advertising campaign which someone else created, specifically wondered why we put on a pedestal those who voyage into space when he and his clever friends were changing the world–or something–with their gadgets. He believed technologists were the best and brightest Americans. He was wrong.

Some of the Valley’s biggest names filed dourly into Trump Tower recently in a sort of reverse perp walk. It was the same, sad spectacle of Al Gore’s pilgrimage, which was answered with Scott Pruitt, climate-change denier, being chosen EPA Chief. Perhaps they made the trek on some sort of utilitarian impulse, but I would guess there was also some element of self-preservation, not an unheard of sense of compromise for those who see their corporations as if they were countries, not only because of their elephantine “GDPs,” but also because of how they view themselves. I don’t think they’re all Peter Thiel, an emotional leper and intellectual fraud who now gets to play out his remarkably stupid theories in a large-scale manner. I’ve joked that Thiel has a moral blind spot reminiscent of Hitler’s secretary, but the truth is probably far darker.

What would have been far more impressive would have been if Musk, Cook, Page, Sandberg, Bezos and the rest stopped downstairs in front of the building and read a statement saying that while they would love to aid any U.S. President, they could not in this case because the President-Elect has displayed vicious xenophobia, misogyny and callous disregard for non-white people throughout the campaign and in the election’s aftermath. He’s shown totalitarian impulses and has disdain for the checks and balances that make the U.S. a free country. In fact, with his bullying nastiness he continues to double down on his prejudices, which has been made very clear by not only his words but through his cabinet appointments. They could have stated their dream for the future doesn’t involve using Big Data to spy on Muslims and Mexicans or programming 3D printers to build internment camps on Mars. They might have noted that Steve Bannon, whom Trump chose as his Chef Strategist, just recently said that there were too many Asian CEOs in Silicon alley, revealing his white-nationalistic ugliness yet again. They could have refused to normalize Trump’s odious vision. They could have taken a stand.

They didn’t because they’re not our absolute finest citizens. Khizr and Ghazala Khan, who understand the essence of the nation in a way the tech billionaires do not, more truly represent us at our most excellent. They possess a wisdom and moral courage that’s as necessary as the Constitution itself. The Silicon Valley folks lack these essential qualities, and without them, you can’t be called our best and brightest.

And maybe Khan’s DNC speech is our ultimate Cassandra moment, when we didn’t listen, or maybe we did but when we looked deep inside for our better angels we came up empty. Regardless, he told the truth beautifully and passionately. When we went low, he went high.

34) “The Perfect Weapon: How Russian Cyberpower Invaded the U.S.” (Eric Lipton, David E. Sanger and Scott Shane)

It was thought that the Russian hacking of the U.S. Presidential election wasn’t met with an immediate response because no one thought Trump really had a chance to win, but the truth is the gravity of this virtual Watergate initially took even many veteran Washington insiders by surprise. This great piece of reportage provides deep and fascinating insight into one of the jaw-dropping scandals of an outrageous election season, which has its origins in the 1990s.

35) “Goodbye to Barack Obama’s World” (Edward Luce, The Financial Times)

“He must be taken seriously,” Luce wrote in the Financial Times in December 2015 of Donald Trump, as the anti-politician trolled the whole of America with his Penthouse-Apartment Pinochet routine, which seems to have been more genuine than many realized.

Like most, the columnist believed several months earlier that the Reality TV Torquemada was headed for a crash, though he rightly surmised the demons Trump had so gleefully and opportunistically awakened, the vengeful pangs of those who longed to Make America Great White Again, were not likely to dissipate.

But the dice were kind to the casino killer, and a string of accidents and incidents enabled Trump and the mob he riled to score enough Electoral College votes to turn the country, and world, upside down. It’s such an unforced error, one which makes Brexit seem a mere trifle, that it feels like we’ve permanently surrendered something essential about the U.S., that more than an era has ended.

In this post-election analysis, Luce looks forward for America and the whole globe and sees possibilities that are downright ugly.

36) “The Writer Who Was Too Strong To Live” (Dave McKenna, Deadspin)

A postmortem about Jennifer Frey, a journalistic prodigy of the 1990s who burned brilliantly before burning out. A Harvard grad who was filing pieces for newspapers before she was even allowed to drink–legally, that is–Frey was a full-time sportswriter for the New York Times by 24, out-thinking, out-hustling and out-filing even veteran scribes at a clip that was all but impossible. Frey seemed to have it all and was positioned to only get more.

Part of what she had, though, that nobody knew about, was bipolar disorder, which she self-medicated with a sea of alcohol. Career, family and friends gradually floated away, and she died painfully and miserably at age 47. The problem with formidable talent as much as with outrageous wealth is that it can be forceful enough to insulate a troubled soul from treatment. Then, when the fall finally occurs, as it must, it’s too late to rise once more.

37) “United States of Paranoia: They See Gangs of Stalkers” (Mike McPhate, The New York Times)

Sometimes mental illness wears the trappings of the era in which it’s experienced. Mike Jay has written beautifully in the last couple of years about such occurrences attending the burial of Napoleon Bonaparte and the current rise of surveillance and Reality TV. The latter is something of a Truman Show syndrome, in which sick people believe they’re being observed, that they’re being followed. To a degree, they’re right, we all are under much greater technological scrutiny now, though these folks have a paranoia which can drive such concerns into crippling obsessions.

Because we’re all connected now, the “besieged” have found one another online, banning together as “targeted individuals” who’ve been marked by the government (or some other group entity) for observation, harassment and mind control. McPhate’s troubling article demonstrates that the dream of endless information offering lucidity has been dashed for a surprising amount of people, that the inundation of data has served to confuse rather than clarify. These shaky citizens resemble those with alien abduction stories, except they seem to have been “shanghaied” by the sweep of history.

38) “The Long-Term Jobs Killer Is Not China. It’s Automation.“ (Claire Cain Miller, The New York Times)

Many people nowadays wonder what will replace capitalism, but I believe capitalism will be just fine.

You and me, however, we’re fucked.

The problem is that an uber technologized version of capitalism may not require as many of us or value as highly those who’ve yet to be relieved of their duties. Perhaps a thin crust at the very top will thrive, but without sound policy the rest may be Joads with smartphones. In this scenario, we’d be tracked and commodified, given virtual trinkets rather than be paid. Our privacy, like many of our jobs, will disappear into the zeros and ones.

While the orange supremacist was waving his penis in America’s face during the campaign, the thorny question of what to do should widespread automation be established was left unexplored. That’s terrifying, since more and more outsourcing won’t refer to work moved beyond borders but beyond species. Certainly great investment in education is required, but that won’t likely be enough. Not every freshly unemployed taxi driver can be upskilled into a driverless car software engineer. There’s not enough room on that road.

Miller, a reporter who understands both numbers and people in a way few do, analyzes how outsourcing will increasingly refer to work not moved beyond borders but beyond species.

39) “Nothing To Fear But Fear Itself” (Sasha Von Oldershausen, Texas Monthly)

Surveillance is a murky thing almost always attended by a self-censorship, quietly encouraging citizens to abridge their communication because perhaps someone is watching or listening. It’s a chilling of civil rights that happens in a creeping manner. Nothing can be trusted, not even the mundane, not even your own judgement. That’s the goal, really, of such a system–that everyone should feel endlessly observed.

The West Texas border reporter finds similarities between her stretch of America, which feverishly focuses on security from intruders, and her time spent living under theocracy in Iran.

40) “Madness” (Eyal Press, The New Yorker)

“By the nineties, prisons had become America’s dominant mental-health institutions,” writes Press in this infuriating study of a Florida correctional facility in which guards tortured, brutalized, even allegedly murdered, inmates–and employed retaliatory measures against mental health workers who complained. Prison reform is supposedly one of those issues that has bipartisan support, but very little seems to get done in rehabilitating a system that warehouses many nonviolent offenders and mentally ill people among those who truly need to be incarcerated. It seems a breakdown of the institution but is more likely a perpetuation of business as it was intended to be. Either way, the situation needs all the scrutiny and investigation journalists can muster.

41) It May Not Feel Like Anything To Be an Alien” (Susan Schneider, Nautilus)

Until deep into the twentieth century, most popular dreams of ETs usually centered on biology. We wanted new friends that reminded us of ourselves or were even cuter. When we accepted we had no Martian doppelgangers, a dejected resignation set in. Perhaps some sort of simple cellular life existed somewhere, but what thin gruel to digest.

Then a new reality took hold: Maybe advanced intelligence exists in space as silicon, not carbon. It’s postbiological.

If there are aliens out there, maybe they’re conscious machines, not oxygen-hoarding humans. It’s just too inhospitable for beings like us to travel beyond our solar system. He allows that cyborgs, a form of semi-organic post-humans, could possibly make a go of it. But that’s as close a reflection of ourselves we may be able to see in space.

Soon enough, that may be true as well on Earth, a relatively young planet on which intelligence may be in the process of shedding its mortal coil. Another possibility: Perhaps intelligence is also discarding consciousness.

Schneider’s smart article asserts that “soon, humans will no longer be the measure of intelligence on Earth” and tries to surmise what that transition will mean.

42) “Schadenfreude with Bite” (Richard Seymour, London Review of Books)

The problem with anarchy is that it has a tendency to get out of control.

In 2013, Eric Schmidt, the most perplexing of Googlers, wrote (along with Jared Cohen) the truest thing about our newly connected age: “The Internet is the largest experiment involving anarchy in history.”

Yes, indeed.

California was once a wild, untamed plot of land, and when people initially flooded the zone, it was exciting if harsh. But then, soon enough: the crowds, the pollution, the Adam Sandler films. The Golden State became civilized with laws and regulations and taxes, which was a trade-off but one that established order and security. The Web has been commodified but never been truly domesticated, so while the rules don’t apply it still contains all the smog and noise of the developed world. Like Los Angeles without the traffic lights.

Our new abnormal has played out for both better and worse. The fan triumphed over the professional, a mixed development that, yes, spread greater democracy on a surface level, but also left truth attenuated. Into this unfiltered, post-fact, indecent swamp slithered the troll, that witless, cowardly insult comic.

The biggest troll of them all, Donald Trump, the racist opportunist who stalked our first African-American President demanding his birth certificate, is succeeding Obama in the Oval Office, which is terrible for the country if perfectly logical for the age. His Lampanelli-Mussolini campaign also emboldened all manner of KKK 2.0, manosphere and neo-Nazi detritus in their own trolling, as they used social media to spread a discombobulating disinformation meant to confuse and distract so hate could take root and grow. No water needed; bile would do.

In the wonderfully written essay, Seymour analyzes the discomfiting age of the troll.

43) “An American Tragedy” (David Remnick, The New Yorker)

It happened here, and Remnick, who spent years covering the Kremlin and many more thinking about the White House, was perfectly prepared to respond to a moment he hoped would never arrive. As the unthinkable was still unfolding and most felt paralyzed by the American embrace of a demagogue, the New Yorker EIC urgently warned of the coming normalization of the incoming Administration, instantly drawing a line that allowed for myriad voices to demand decency and insist on truth and facts, which is our best safeguard against the total deterioration of liberal governance.

44) “This Is New York in the Not-So-Distant Future” (Andrew Rice, New York)

Some sort of survival mechanism allows us to forget the full horror of a tragedy, and that’s a good thing. That fading of facts makes it possible for us to go on. But it’s dangerous to be completely amnesiac about disaster.

Case in point: In 2014, Barry Diller announced plans to build a lavish park off Manhattan at the pier where Titanic survivors came to shore. Dial back just a little over two years ago to another waterlogged disaster, when Hurricane Sandy struck the city, and imagine such an island scheme even being suggested then. The wonder at that point was whether Manhattan was long for this world. Diller’s designs don’t sound much different than the captain of a supposedly unsinkable ship ordering a swimming pool built on the deck just after the ship hit an iceberg.

Rice provides an excellent profile of scientist Klaus Joseph, who believes NYC, as we know it, has no future. The academic could be wrong, but if he isn’t, his words about the effects of Irene and Sandy are chilling: “God forbid what’s next.”

45) “The Newer Testament” (Robyn Ross, Texas Monthly)

A Lone Star State millennial using apps and gadgets to disrupt Big Church doesn’t really seem odder than anything else in this hyperconnected and tech-happy entrepreneurial age, when the way things have been are threatened at every turn. At Experience Life in Lubbock, Soylent has yet to replace wine and there’s no Virtual Reality confessionals, but self-described “computer nerd” Chris Galanos has done his best to take the “Old” out of the Old Testament with his buzzing, whirring House of God 2.0. Is nothing sacred anymore?

46) “The New Nationalism Of Brexit And Trump Is A Product Of The Digital Age” (Douglas Rushkoff, Fast Company)

“We are flummoxed by today’s nationalist, regressively anti-global sentiments only because we are interpreting politics through that now-obsolete television screen,” writes Rushkoff in this excellent piece about the factious nature of the Digital Age. The post-TV landscape is a narrowcasted one littered with an infinite number of granular choices and niches. It’s empowering in a sense, an opportunity to vote “Leave” to everything, even a future that’s arriving regardless of popular consensus. It’s a far cry from not that long ago when an entire world sat transfixed by Neil Armstrong’s giant leap. Now everyone is trying to land on the moon at the same time–and no one can agree where it is. It’s more democratic this way, but maybe to an untenable degree, perhaps to the point where it’s a new form of anarchy.

47) “The Incredible Fulk” (Alexandra Suich, The Economist 1843)

The insanity of our increasingly scary wealth inequality is chronicled expertly in this richly descriptive article, even though it seems in no way intended as a hit piece. The title refers to Ken Fulk, Silicon Valley’s go-to “lifestyle designer,” who charges billionaires millions to create loud interiors, rooms stuffed with antique doors from shuttered mental institutions and musk-ox taxidermy, intended to “evoke feelings” or some such shit.

As the article says: “His spaces, when completed, have a theatrical quality to them, which Fulk plays up. Once he’s finished a project he often brings clients to their homes to show them the final product, a ceremony which he calls the ‘big reveal.’ For the Birches’ home in San Francisco, he hired men dressed as beefeaters to stand outside the entrance and musicians to play indoors. For another set of clients in Palm Springs, he hired synchronized swimmers, a camel and an impersonator to dress up and sing like Dean Martin.” It’s all good, provided a bloody revolution never occurs.

Fulk acknowledges a “tension between high and low” in his work. Know what else has tension? Nooses.

48) “Truth Is a Lost Game in Turkey. Don’t Let the Same Thing Happen to You.” (Ece Temelkuran, The Guardian)

Nihilism is sometimes an end but more often a means.

Truth can be fuzzy and facts imprecise, but an honest pursuit of these precious goods allows for a basic decency, a sense of order. Bombard such efforts for an adequate length of time, convince enough people that veracity and reality are fully amorphous, and opportunities for mischief abound.

Break down the normal rules (written and unwritten ones), create an air of confusion with shocking behaviors and statements, blast an opening where anything is possible–even “unspeakable things”–and a democracy can fall and tyranny rise. The timing has to be right, but sooner or later that time will arrive.

Has such a moment come for America? The conditions haven’t been this ripe for at least 60 years, and nothing can now be taken for granted.

Temelkuran explains how Turkey became a post-truth state, a nation-sized mirage, and how the same fate may befall Europe and the U.S. She certainly shares my concerns about the almost non-stop use of the world “elites” to neutralize the righteous into paralysis.

49) “Prepping for Doomsday: Bunkers, Panic Rooms, and Going Off the Grid” (Clare Trapasso, Realtor.com)

Utter societal collapse in the United States may not occur in the immediate future, but it’s certainly an understandable time for a case of the willies. In advance of the November elections, the bunker business boomed, as some among us thought things would soon fall apart and busied themselves counting their gold coins and covering their asses. In a shocking twist, the result of the Presidential election has calmed many of the previously most panicked among us and activated the fears of the formerly hopeful.

50) “The 100-Year-Old Man Who Lives in the Future” (Caroline Winter, Bloomberg Businessweek)

Jacque Fresco, one of those fascinating people who walks through life building a world inside his head, hoping it eventually influences the wider one, is now into his second century of life. A futurist and designer who’s focused much of his work on sustainable living, technology and automation, Fresco is the brains behind the Venus Project, which encourages a post-money, post-scarcity, post-politician utopia. He’s clearly a template for many of today’s Silicon Valley aspiring game-changers.

Winter traveled to Middle-of-Nowhere, Florida (pop: Fresco + girlfriend and collaborator Roxanne Meadows), to write this smart portrait of the visionary after ten decades of reimagining the world according to his own specifications. He doesn’t think the road to a computer-governed utopia will be smooth, however. As Winter writes: “Once modern life gets truly hard, Fresco believes there will be a revolution that will clear the way for the Venus Project to be built. ‘There will be a lot of people getting shot, including me,’ he says wryly.” Well, he’s had a good run.•