Of the many consequences, intended and not, of driverless cars, the fate of Uber is one of the least important unless you happen to be an investor in the rideshare company or an interested party hoping to see Travis Kalanick’s oft-irresponsible outfit get driven from the road. More vital will be the disappearance of millions of jobs, the saving of that many lives over time, the impact on the environment, etc.

Still, it’s a fascinating business story. Uber’s massive disruption of the taxi industry may be soon viewed as a staggering, though short-lived, victory, much the way CDs wrecked the market for LPs and cassettes, before being quickly usurped by a better technology.

When autonomous cars do become a going concern, eventually there won’t be any need for a middle man, and, perhaps, ownership of any kind. The fleets will drive themselves in all senses.

Two new excerpts on the topic are followed by a piece from a retro 1969 National Geographic feature.

From a Forbes article by Chunka Mui about Google driverless guru Chris Urmson’s predictions for the sector:

To the inevitable question of “when,” Urmson is very optimistic. He predicts that self-driving car services will be available in certain communities within the next five years.

You won’t get them everywhere. You certainly not going to get them in incredibly challenging weather or incredibly challenging cultural regions. But, you’ll see neighborhoods and communities where you’ll be able to call a car, get in it, and it will take you where you want to go.

(Based on recent Waymo announcements, Phoenix seems a likely candidate.)

Then, over the next 20 years, Urmson believes we’ll see a large portion of the transportation infrastructure move over to automation.

Urmson concluded his presentation by calling it an exciting time for roboticists. “It’s a pretty damn good time to be alive. We’re seeing fundamental transformations to the structure of labor and the structure transportation. To be a part of that and have a chance to be involved in it is exciting.”•

The opening of Christopher Mims’ smart WSJ piece about the potential fall of Uber:

If Uber Technologies Inc. ever collapses, historians may trace its undoing not to its troubles with labor relations, intellectual property, regulatory conflicts or sexual-harassment allegations, but to technological disruption.

This would be the same technological disruption the company itself pledged to use to upend the auto industry and the $2 trillion a year tied to it.

Less than a year ago, Uber Chief Executive Travis Kalanick described self-driving cars as an “existential” threat to his company, saying that his team must get the technology to market before competitors do, or at least at around the same time. Self-driving vehicles would ultimately be much cheaper to operate than ones requiring human drivers—robots work tirelessly and don’t demand raises. The first companies to roll out fleets of automated taxis could quickly drive their human-powered competition into oblivion.

Uber’s philosophy, both internally and in its pitch to consumers, is that it’s a hassle to own a car. The irony is, for the pay-by-the-ride future of transportation to be realized, someone has to own a lot of cars. Chances are, it won’t be Uber.•

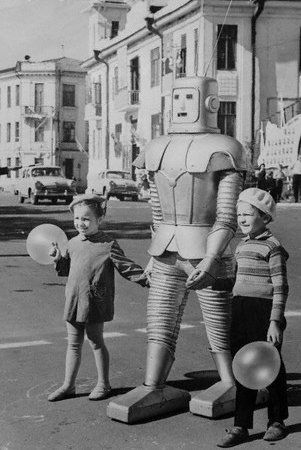

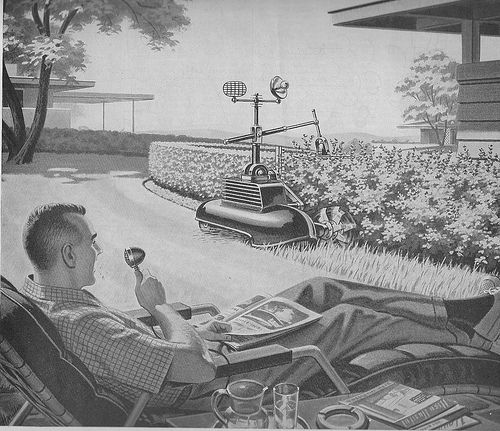

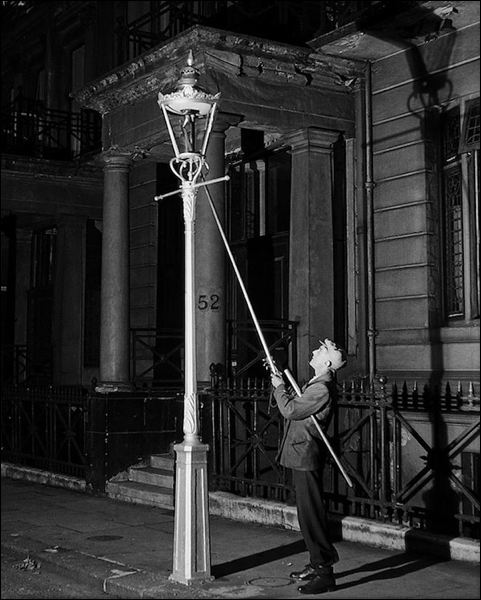

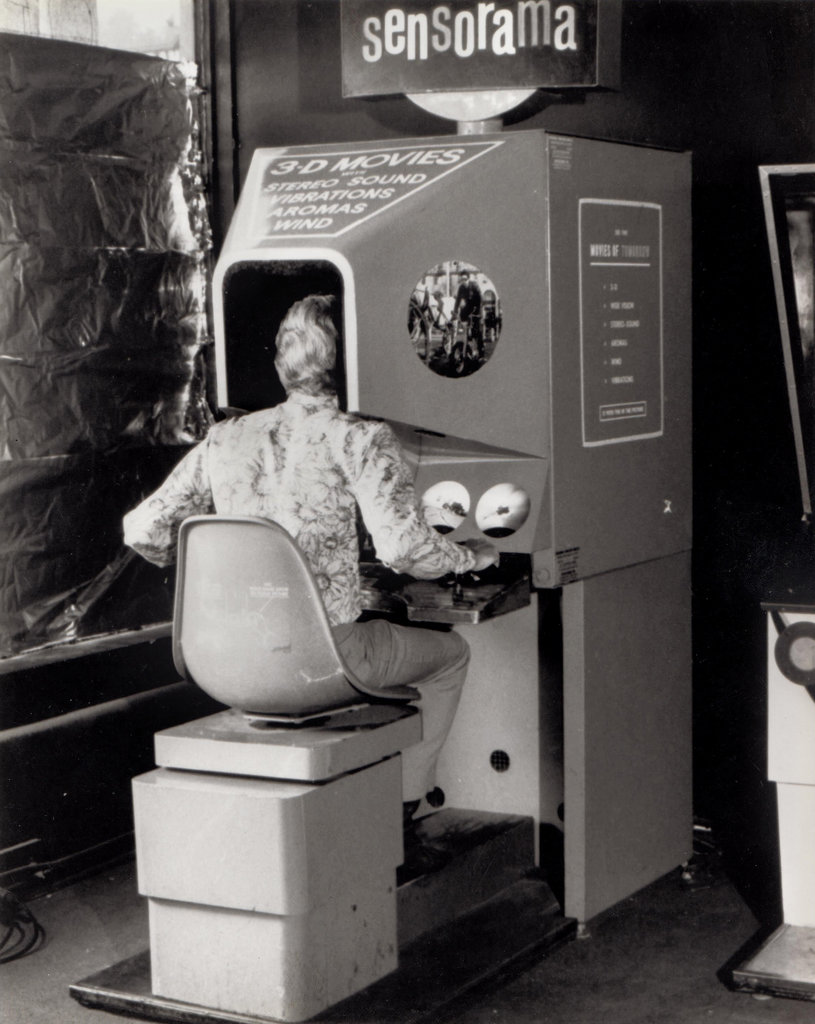

Three months before we reached the moon, a moment when machines eclipsed, in a meaningful way, the primacy of humanity, National Geographic published the 1969 feature “The Coming Revolution in Transportation,” penned by Frederic C. Appel and Dean Conger. The article prognosticated some wildly fantastical misses as any such futuristic article would, but it broadly envisioned the next stage of travel as autonomous and, perhaps, electric.

The two excerpts I’ve included below argue that tomorrow’s transportation would in, one fashion or another, remove human hands from the wheel. The second passage particularly relates to the driverless sector of today. Interesting that we’re skipping the top-down step of building “computer-controlled” or “automated” highways, something suggested as necessary in this piece, as an intensive infrastructure overhaul never materialized. We’re attempting instead to rely on visual-recognition systems and an informal swarm of gadgets linked to the cloud to circumvent what was once considered foundational.

· · ·

“People Capsule”: Dial Your Destination

Everywhere I found signs that a revolution in transportation is on the way.

The automobile you drive today could probably move at 100 miles an hour. But you average closer to 10 as you travel our clogged city streets.

Someday, perhaps in your lifetime, it could be like this….

You ride toward the city at 90 miles an hour, glancing through the morning newspaper while your electrically powered car follows its route on the automated “guideway.”

You leave your car at the city’s edge–a parklike city without streets–and enter on the small plastic “people capsules” waiting nearby. Inside, you dial your destination on a sequence of numbered buttons. Then you settle back to reading your paper.

Smoothly, silently, your capsule accelerates to 80 miles an hour. Guided by a distant master computer, it slips down into the network of tunnels under the city–or into tubes suspended above it–and takes precisely the fastest route to your destination.

Far-fetched? Not at all. Every element of that fantastic people-moving system is already within range of our scientists’ skills.

· · ·

· · ·

Car-trunk Computer Issues Orders

Consider automated cars–and when you do, look at the modern automobile. Think of the rapid increase, in the past decade, of electric servomechanisms on automobiles. Power steering, antiskid power brakes, adjustable seats, automatic door locks, automatic headlight dimmers, electronic speed governors, self-regulated air conditioning.

Detroit designers, already preparing for the day your vehicle will drive itself, are getting practical experience with the automatic devices on today’s cars. When more electric devices are added and the first computer-controlled highways are built, the era of the automated car will be here.

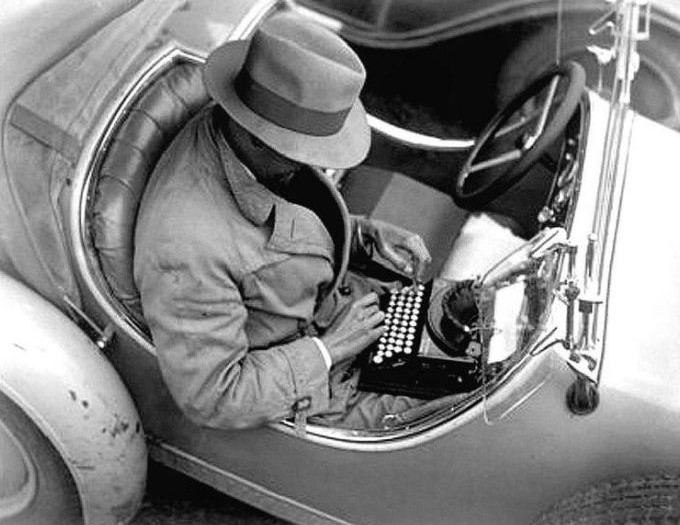

At the General Motors Technical Center near Detroit, I drove a remarkable vehicle. It was the Unicontrol Car, one step along the way to the automated family sedan.

In the car a small knob next to the seat (some models have dual knobs) replaced steering wheel, gearshift lever, accelerator and brake pedal.

Moving that knob, I learned, sends electronic impulses back to a sort of “baby computer” in the car’s trunk. The computer translates those signals into action by activating the proper servomechanism–steering motor, power brakes, or accelerator.

Highways May Take Over the Driving

Simple and ingenious, I thought, as I slid into the driver’s seat. Gingerly I pushed the knob forward. Somewhere, unseen little robots released the brake and stepped on the gas.

So far, so good. Now I twitched the knob to the left–and very nearly made a 35-mile-an-hour U-turn!

But after a few minutes of practice, I found that the strange control method really did feel comfortably logical. I ended my half-hour test drive with a smooth stop in front of a Tech Center office building and headed upstairs to call on Dr. Lawrence R. Hafstad, GM’s Vice President in Charge of Research Laboratories.

The Unicontrol Car–a research vehicle built to test new servomechanisms–is easy to drive. Still, it does have to be driven. I asked Dr. Hafstad about the proposed automated highways that would relieve the driver of all responsibilities except that of choosing a destination.

“Automated highways–engineers call them guideways–are technically feasible today,’ Dr. Hafstad answered. “In fact, General Motors successfully demonstrated an electronically controlled guidance system about ten years ago. A wire was embedded in the road, and two pickup coils were installed at the front of the car to sense its position in relation to that wire. The coils sent electrical signals to the steering system, to keep the vehicle automatically on course.

“More recently, we tested a system that also controlled spacing and detected obstacles. It could slow down an overtaking vehicle–even stop it, until the road was clear!”

Other companies are also experimenting with guideways. In some systems, the car’s power comes from an electronic transmission line built into the road. In others, vehicles would simply be carried on a high-speed conveyor, or perhaps in a container. Computerized guidance systems vary, too.

“Before the first mile of automated highway is installed,” Dr. Hafstad pointed out, “everyone will have to agree on just which system is to be used.”•

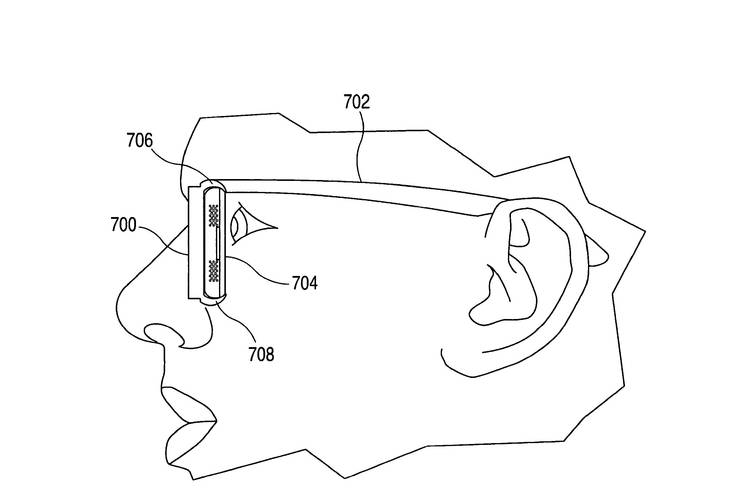

The knock on Apple in the post-Jobs era (from me included) has been the lack of new products, the company becoming wealthier mainly from extending the popularity of its iPhone into the Chinese market. It doesn’t seem like that growth can continue, except if Apple can successfully integrate that technology very deeply into society. That’s what Tim Cook hopes will result from sizable investments in AI and AR and other next-level tools, dreaming of a product well beyond Google Glass, less obtrusive and more connected, and far more wide-reaching than the Echo sitting on your coffee table. It will be ambient and ubiquitous.

The knock on Apple in the post-Jobs era (from me included) has been the lack of new products, the company becoming wealthier mainly from extending the popularity of its iPhone into the Chinese market. It doesn’t seem like that growth can continue, except if Apple can successfully integrate that technology very deeply into society. That’s what Tim Cook hopes will result from sizable investments in AI and AR and other next-level tools, dreaming of a product well beyond Google Glass, less obtrusive and more connected, and far more wide-reaching than the Echo sitting on your coffee table. It will be ambient and ubiquitous.