Terrorism developed as a way for weak factions to disrupt war, to hack what had been a very centralized activity since the formation of discrete states. The thing is, such ad hoc chicanery hardly ever works, at least ultimately. Eventually the element of surprise is identified, neutralized.

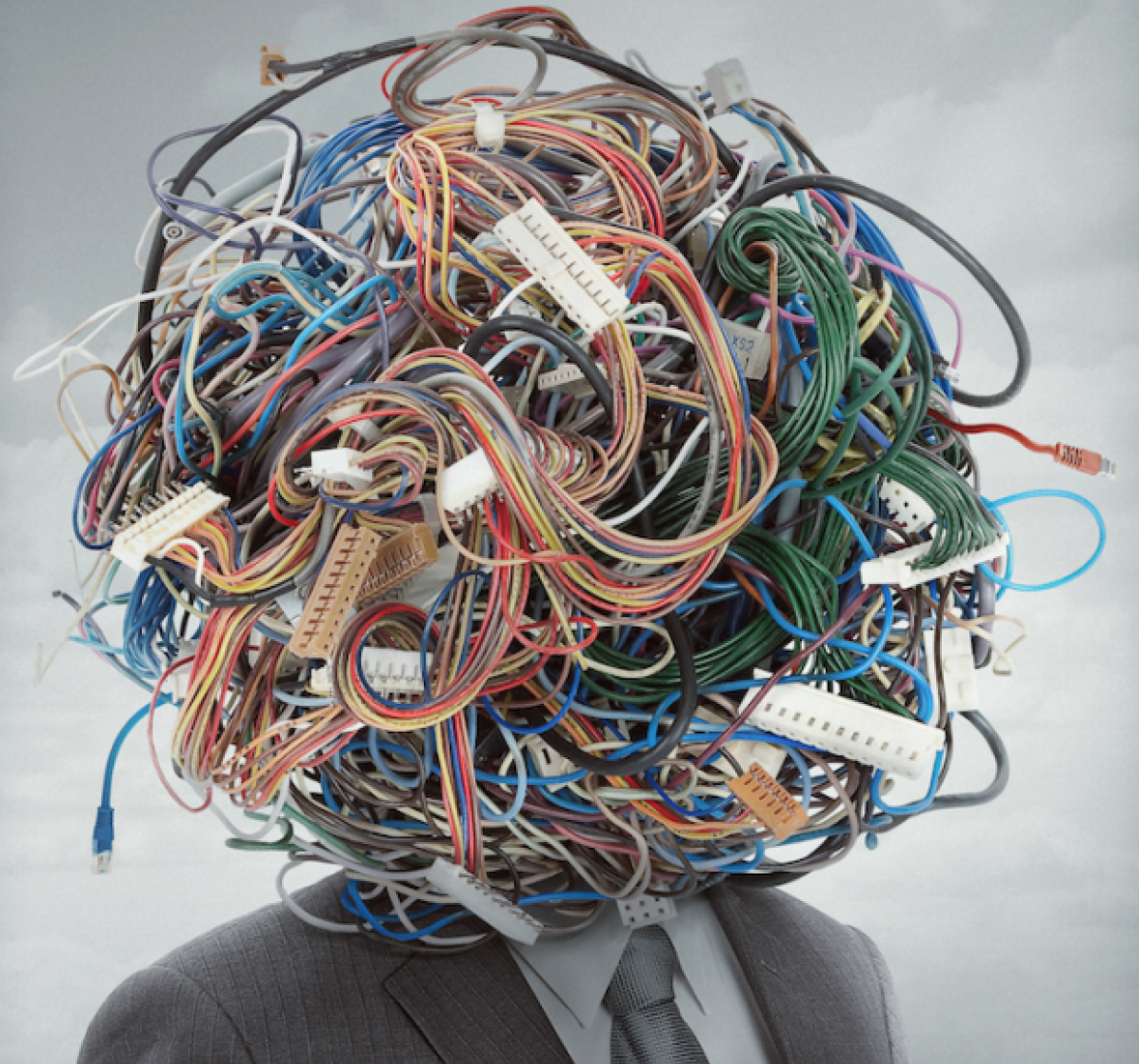

Our new tech tools, however, have begun to level the playing field. Sure, ISIS still can’t hack its way to heaven in 2017, but a fully formed terror state like Russia managed for a very reasonable sum to successfully wage “memetic warfare” against America, a much wealthier and militarily superior nation, albeit, with what would appear to be aid and comfort from a cabal of traitors. As the world grows ever more computerized, perhaps eventually we’ll all have an army to do our bidding and every target, real and virtual, will be made vulnerable.

From John Thornhill of the Financial Times:

Most defense spending in NATO countries still goes on crazily expensive metal boxes that you can drive, steer, or fly. But, as in so many other areas of our digital world, military capability is rapidly shifting from the visible to the invisible, from hardware to software, from atoms to bits. And that shift is drastically changing the equation when it comes to the costs, possibilities and vulnerabilities of deploying force. Compare the expense of a B-2 bomber with the negligible costs of a terrorist hijacker or a state-sponsored hacker, capable of causing periodic havoc to another country’s banks or transport infrastructure — or even democratic elections.

The US has partly recognized this changing reality and in 2014 outlined a third offset strategy, declaring that it must retain supremacy in next-generation technologies, such as robotics and artificial intelligence. The only other country that might rival the US in these fields is China, which has been pouring money into such technologies too.

But the third offset strategy only counters part of the threat in the age of asymmetrical conflict. In the virtual world, there are few rules of the game, little way of assessing your opponent’s intentions and capabilities, and no real clues about whether you are winning or losing. Related article Donald Trump is the odd man out with Putin and Xi China and Russia co-operate in areas posing a challenge to western interests Such murkiness is perfect for those keen to subvert the west’s military strength.

China and Russia appear to understand this new world disorder far better than others — and are adept at turning the west’s own vulnerabilities against it. Chinese strategists were among the first to map out this new terrain. In 1999 two officers in the People’s Liberation Army wrote Unrestricted Warfare in which they argued that the three indispensable “hardware elements of any war” — namely soldiers, weapons and a battlefield — had changed beyond recognition. Soldiers included hackers, financiers and terrorists. Their weapons could range from civilian aeroplanes to net browsers to computer viruses, while the battlefield would be “everywhere.”

Russian strategic thinkers have also widened their conception of force.•