Ken Kesey responded this way when asked if psychedelics had injured him: “You don’t get anything for free.”

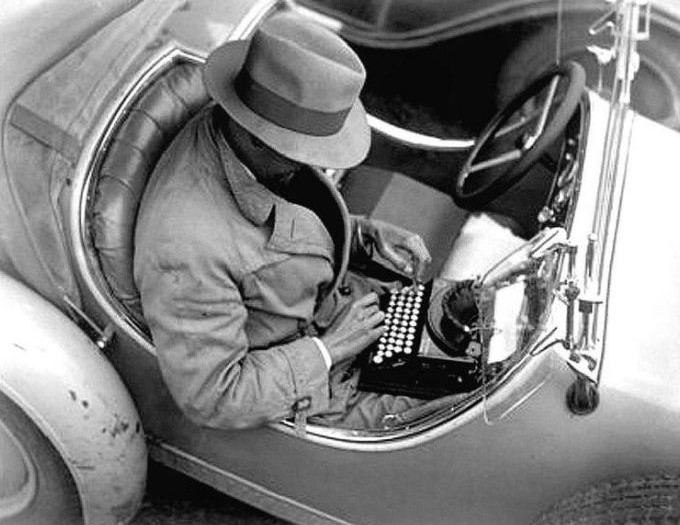

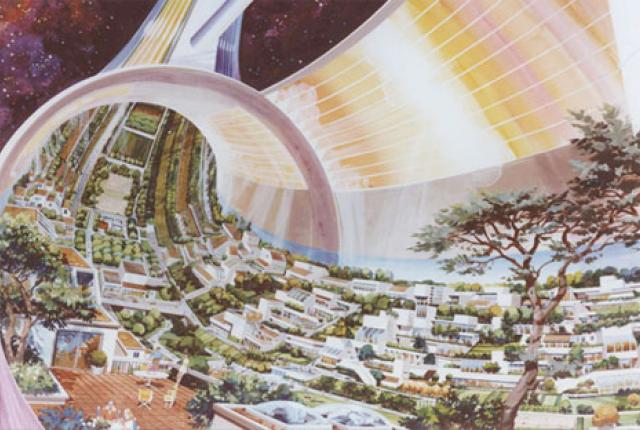

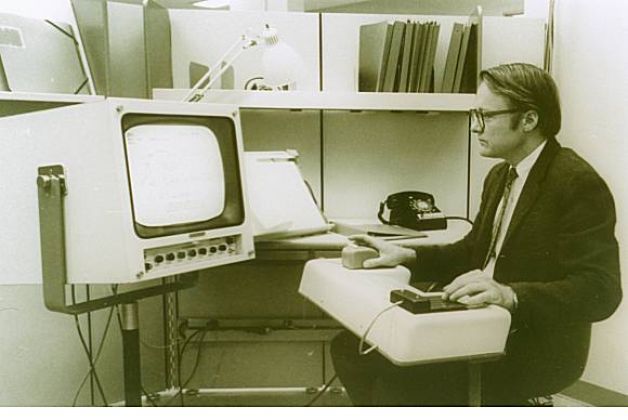

Buried in Timothy Leary’s original 1960s “Turn on, tune in, drop out” college lecture tour was the defrocked academic’s belief that while the mind-bending strength of LSD was needed to awaken the “beloved robots” from society’s lockstep sleepwalk, he didn’t think pharmaceuticals would long be required or even desired to liberate hearts and minds. Leary felt computer software or space exploration or some other “high” would allow people to escape conformity.

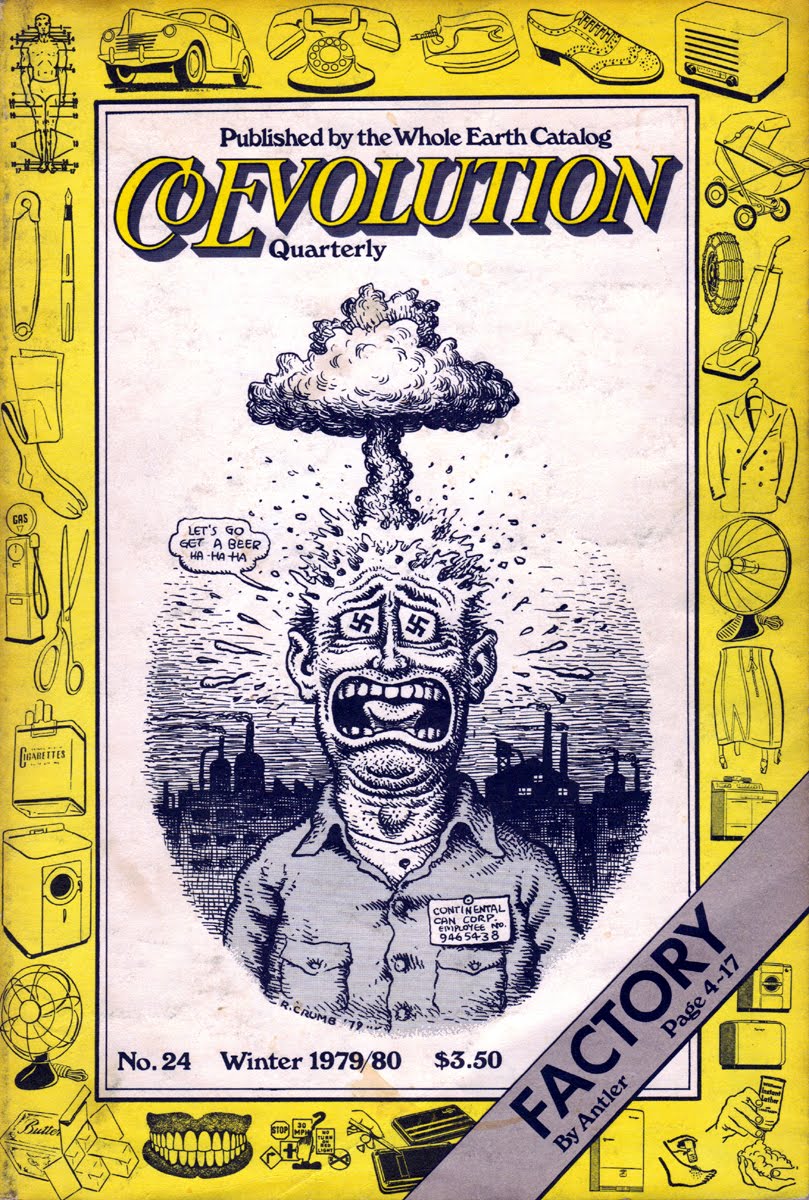

We’re 50 years on from the famous (and infamous) Trips Festival in San Francisco, the first real gathering of hippies, with Owsley Stanley providing the dosage and the Grateful Dead the volume. All those years later, America has a President-Elect reminiscent of Mussolini and a populace that’s largely turned cruel. Is that because not enough people became enlightened or due to progress and regress being constantly at war? The latter, I think.

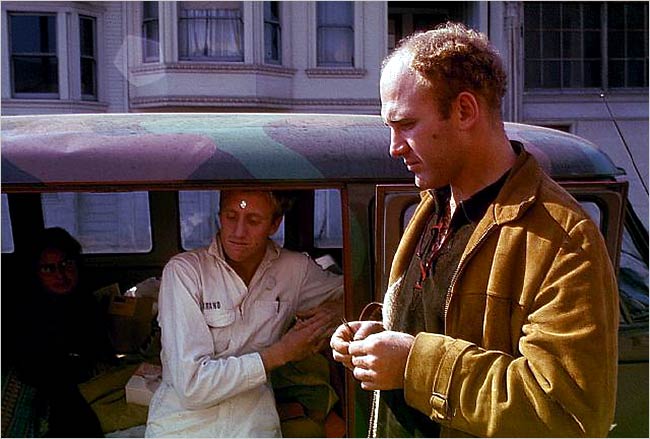

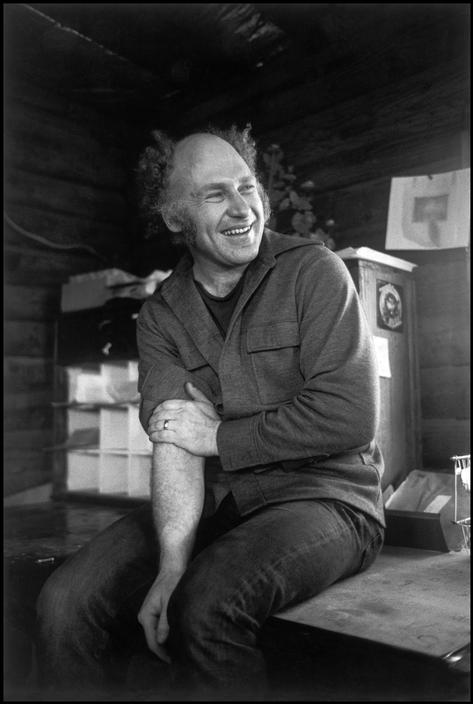

Regardless, a golden-anniversary celebration of the seminal event will be attended by one of its original organizers Stewart Brand. He was interviewed by Gabe Meline of KQED about the occasion. Below is an excerpt from that Q&A and a piece from Brand’s 1967 Psychedelic Review article about a peyote-fueled Native American church meeting he attended.

From KQED:

Question:

You’re someone who often thinks about, and talks about, the future. This going to be thinking and talking about the past — 50 years ago. How does it feel to look back?

Stewart Brand:

Well, the Long Now Foundation, where I am President and have been mainly occupied for the last 20 years — we are focused on continuity. The Trips Festival was a continuity event. It was kind of a transitional event from one period of art in the Bay Area to another period. A lot of what it was expressing then is, I think, still very present — certainly in Burning Man, and in certain relationships that artists have to each other, and, increasingly, that engineers have to each other in the Bay Area. The interaction of engineers and artists, there was a certain amount of it at the Trips Festival and there’s certainly a lot more now. It’s part of the Bay Area’s ongoing contribution to culture and society.

Question:

You mentioned Burning Man. What other things grew out of the ideology at the Trips Festival?

Stewart Brand:

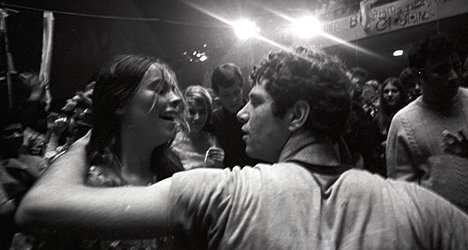

I think one of the main things is the idea of no spectators. The idea that an audience shows up to a certain kind of event expecting to do something, not just to see something. Raves came on through that. People came to the Trips Festival in outfits, and stoned, and prepared to dance. There was not much seating in Longshoreman’s Hall. There was a great big floor with scaffolding in the middle, where Ken Kesey and Ken Babbs and I were dangling. That floor was always filled with people doing stuff. It was at its best when the Grateful Dead, newly named the Grateful Dead, were playing. That’s why we did a reprise Sunday night of their amazing show on Saturday night.•

From Psychedelic Review:

The meeting is mandala-form, a circle with a doorway to the east. The roadman will sit opposite the door, the moon-crescent altar in front of him. To his left sits the cedarman, to his right the drummer. On the right side as you enter will be the fireman. The people sit around the circle. In the middle is the fire.

A while after dark they go in. This may be formal, filling in clockwise around the circle in order. The roadman may pray outside beforehand, asking that the place and the people and the occasion be blessed.

Beginning a meeting is as conscious and routine as a space launch countdown. At this time the fireman is busy starting the fire and seeing that things and people are in their places. The cedarman drops a little powder of cedar needles and little balls, goes down the quickest. In all cases, the white fluff should be removed. There is usually a pot of peyote tea, kept near the fire, which is passed occasionally during the night. Each person takes as much medicine as he wants and can ask for more at any time. Four buttons is a common start. Women usually take less than the men. Children have only a little, unless they are sick.

Everything is happening briskly at this point. People swallow and pass the peyote with minimum fuss. The drummer and roadman go right into the starting song. The roadman, kneeling on one or both knees, begins it with the rattle in his right hand. The drummer picks up the quick beat, and the roadman gently begins the song. His left hand holds the staff, a feather fan, and some sage. He sings four times, ending each section with a steady quick rattle as a signal for the drummer to pause or re-wet the drumhead before resuming the beat. Using his thumb on the drumhead, the drummer adjusts the beat of his song. When the roadman finishes he passes the staff, gourd, fan and sage to the cedarman, who sings four times with the random drumming. So it goes, the drum following the staff to the left around the circle, so each man sings and drums many times during the night.•