The policies favored by the President-Elect and the GOP-controlled Congress will likely cause many Americans to needlessly face harassment, discrimination, financial distress, health problems and, potentially, early death.

That, I fear, is the glass-half-full option.

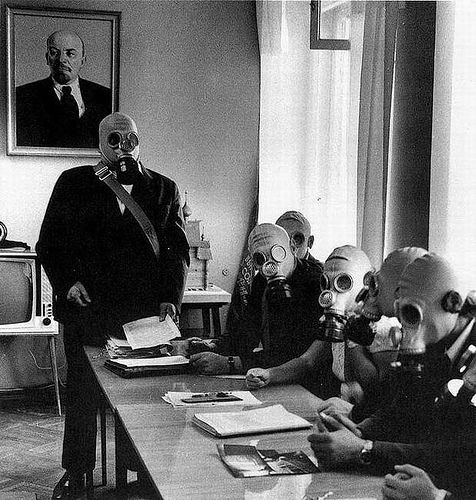

My darker concern is that we’re headed for some 1930s-style “excitement,” an undermining of liberal governance, a rise of fascism and the simultaneous destabilization of numerous militarized, nativistic countries. That’s when the gloves come off.

Hopefully we won’t see the realization of such mass chaos, but Peter Turchin, the father of cliodynamics who’s been warning for awhile about the dangers of wealth inequality and other contemporary ills, isn’t sanguine about the immediate future, though he believes with great effort we can keep our “roller coaster” from a steep fall. The opening of his recent Phys.org article:

Cliodynamics is a new “transdisciplinary discipline” that treats history as just another science. Ten years ago I started applying its tools to the society I live in: the United States. What I discovered alarmed me.

My research showed that about 40 seemingly disparate (but, according to cliodynamics, related) social indicators experienced turning points during the 1970s. Historically, such developments have served as leading indicators of political turmoil. My model indicated that social instability and political violence would peak in the 2020s (see Political Instability May be a Contributor in the Coming Decade).

The presidential election which we have experienced, unfortunately, confirms this forecast. We seem to be well on track for the 2020s instability peak. And although the election is over, the deep structural forces that brought us the current political crisis have not gone away. If anything, the negative trends seem to be accelerating.

My model tracks a number of factors. Some reflect the developments that have been noticed and extensively discussed: growing income and wealth inequality, stagnating and even declining well-being of most Americans, growing political fragmentation and governmental dysfunction.•