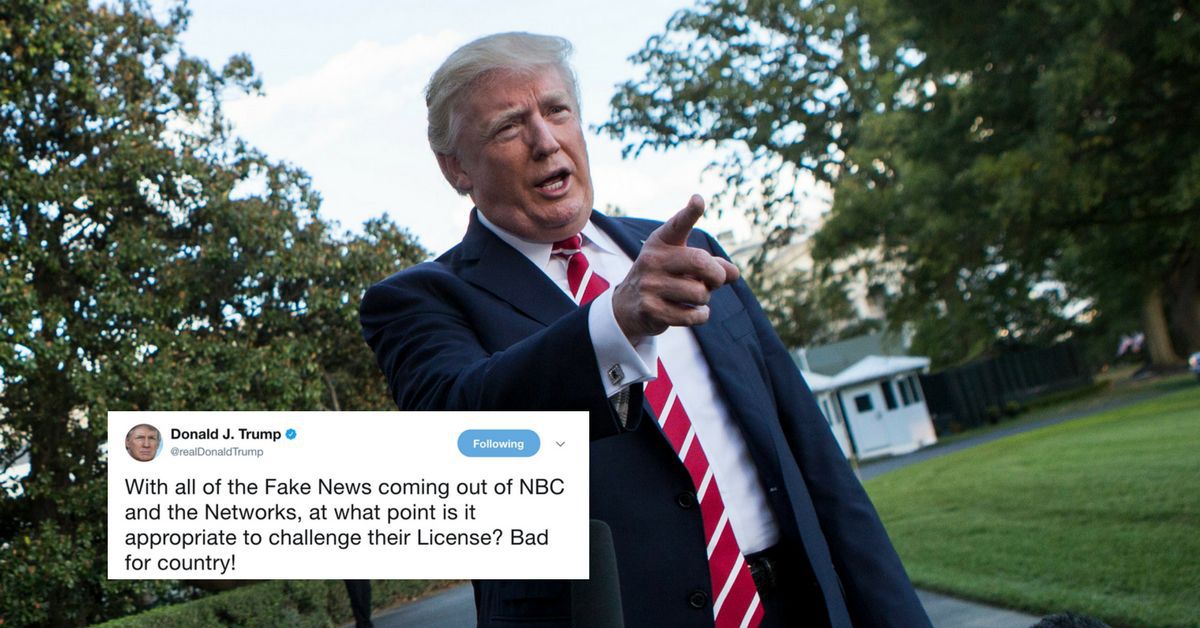

Politely dissented yesterday when a consistently smart commentator on Twitter suggested social media led to the downfall of Harvey Weinstein. It was actually two incredibly expensive, old-school journalism pieces from legacy news organizations (the New York Times and the New Yorker) that deservedly laid him low. The latter of those two outlets is owned by Condé Nast, which is reportedly set to rack up $100 million less in revenues this year than last. We always hear about how much traffic such erstwhile print powerhouses are gaining, but it simply doesn’t translate into a suitable replacement for funds formerly brought in by display ads and classifieds. It’s not clear that video (a bubble, really) or micropayments or some other means will rescue costly, vital journalism, but it won’t be easy sustaining a healthy democracy without it.

Two excerpts follow about liberty in peril.

_______________________

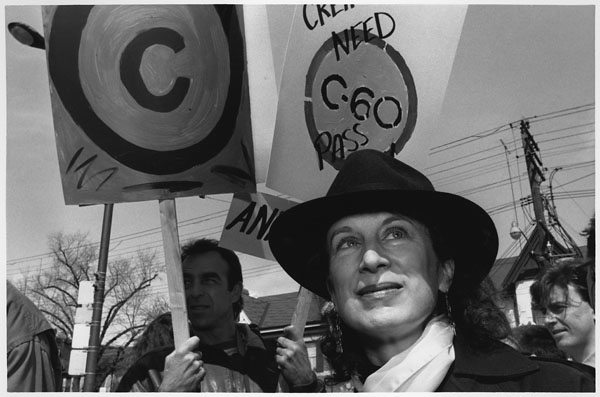

In Douglas Busvine’s Reuters report on Margaret Atwood, the novelist asserts the world is closer than any time since World War II to falling under the sick spell of totalitarianism. That’s true since it hasn’t been a very realistic scenario for the past 70 years, but perhaps the statement lacks necessary proportion. We’re living in a threatening time but not one fated to devolve into dictatorship.

An excerpt:

Donald Trump’s election as U.S. president has, for some critics, brought that vision closer to reality as he uses social media to browbeat opponents, and lawmakers in a number of states seek to restrict women’s reproductive rights.

“It feels the closest to the 1930s of anything that we have had since that time,” the 77-year-old Atwood told a news conference, drawing parallels with the fascist and communist regimes which then ruled parts of Europe. …

Atwood, author of more than 40 books of fiction, poetry and critical essays, said it was surprising to many that signs of totalitarianism were manifesting themselves in the United States of today.

It’s a far cry from the Berlin of the Cold War, still surrounded by the wall that divided Germany, where she started writing The Handmaid’s Tale, she recalled.

“People in Europe saw the United States as a beacon of democracy, freedom, openness, and they did not want to believe that anything like that could ever happen there,” she said.

“But now, times have changed, and, unfortunately it becomes more possible to think in those terms.”•

· · ·

In the New York Review of Books, Sasha Polakow-Suransky asks “Is Democracy in Europe Doomed?” The writer uses polling stats to argue that U.S. senior citizens appreciate democracy but millennials do not. That’s odd since it was older Americans, not our youngest voters, who supported Trump into the White House. An excerpt:

On the morning of April 23, 2017, as the polls opened in the ninth arrondissement of Paris, an old man with a cane positioned himself in front of a bright yellow mailbox and began to scrape. After a few minutes, he sauntered away toward the markets of the rue des Martyrs, leaving a torn and scratched relic of the modified hammer-and-sickle logo of the hard-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s party, La France Insoumise (“Rebellious” or, literally, “Unsubmissive France”).

The old man, evidently no fan of Mélenchon’s anticapitalist, anti-NATO, pro-Russian rhetoric, had reason to worry. In neighborhoods like this, the epicenter of Paris hipsterdom, Mélenchon polled well. Everyone from student protesters to academics and the well-to-do scions of one of the city’s wealthiest families told me they were voting for the ex-communist firebrand. His soaring oratory and rage at the system captivated the left and almost propelled him into the second round; he finished with almost 20 percent of the vote, just 2 percent less than the leader of the National Front (FN), Marine Le Pen.

After the results came in, Mélenchon was the only defeated candidate who did not call upon his followers to back the centrist candidate Emmanuel Macron against Le Pen in the second round. He instead consulted 250,000 of them online and found that two-thirds refused to support Macron. In the days leading up to round two, there was panic on the left. Even the former Communist Party organ L’Humanité printed op-eds calling on readers who had voted for Mélenchon to grudgingly back Macron. According to postelection polls, only half of Mélenchon’s voters did so; many simply stayed home, contributing to the highest abstention rate in decades (25 percent) and the largest number of blank or spoiled ballots (over four million, or 12 percent of all votes) ever recorded.

Le Pen and Mélenchon together drew nearly 50 percent of the youth vote in the first round, splitting the 18-34 age bracket evenly. Unlike in Britain’s Brexit referendum, the young did not support the status quo; they voted for extremists who want to leave the EU.

Those who believe millennials are immune to authoritarian ideas are mistaken. Using data from the World Values Survey, the political scientists Roberto Foa and Yascha Mounk have painted a worrying picture. As the French election demonstrated, belief in core tenets of liberal democracy is in decline, especially among those born after 1980. Their findings challenge the idea that after achieving a certain level of prosperity and political liberty, countries that have become democratic do not turn back.

In America, 72 percent of respondents born before World War II deemed it absolutely essential to live in a democracy; only 30 percent of millennials agreed. The figures were similar in Holland. The number of Americans favoring a strong leader unrestrained by elections or parliaments has increased from 24 to 32 percent since 1995. More alarmingly, the number of Americans who believe that military rule would be good or very good has risen from 6 to 17 percent over the same period. The young and wealthy were most hostile to democratic norms, with fully 35 percent of young people with a high income regarding army rule as a good thing. Mainstream political science, confident in decades of received wisdom about democratic “consolidation” and stability, seemed to be ignoring a disturbing shift in public opinion.

There could come a day when, even in wealthy Western nations, liberal democracy ceases to be the only game in town. And when that day comes, those who once embraced democracy could begin to entertain other options.•