It’s an amazement that in this new millennium people stopped talking on the phone, that we turned away from conversation that travels through the fucking air. That it happened exactly when phones got really good and really portable makes it even more striking.

I always hated talking on the phone on account of my desire to shut the fuck up as much as possible, but I don’t even set up the voicemail on my personal line. I dream of ridding myself of email and Twitter, but I’ve already taken a stand on talking on the phone. I said “goodbye” and returned the receiver to its cradle. That baby will have to raise itself.

A text is inferior to a talk in almost every way. It’s far less human and less intimate (which is exactly why it’s preferred). I imagine Kazuo Ishiguro is capable of intimate tweets, but he may be the only one.

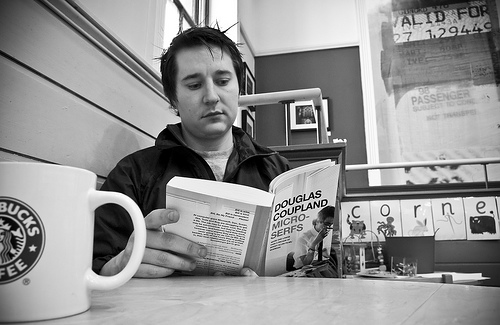

Some clips from a recent Douglas Coupland Financial Times column about this modern disconnect:

My mother is convinced I have a secret phone with a secret phone number. I try to tell her that nobody speaks on phones these days, but she won’t believe it. My outgoing message on my cell is that I don’t check messages. I don’t. I haven’t checked voicemail in more than two years. People still sometimes leave messages. It’s their choice. Gosh! I wonder if I have any voicemail! Not.

• • •

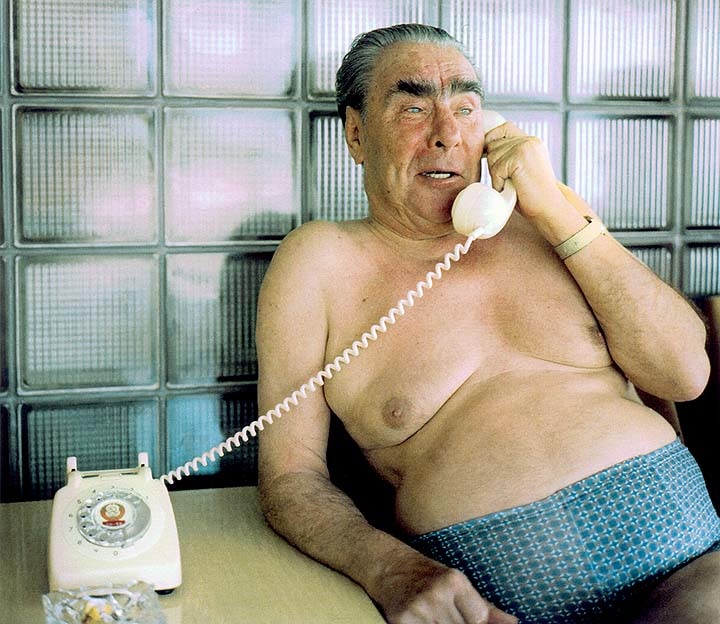

I remember rotary dial phones. They were produced after the second world war in New Jersey by a US government-sanctioned monopoly called Bell Labs. The government thought communications were far too important to be left in the hands of raw capitalism and, to their credit, Bell Labs designed phones of stunning durability — just ask anyone from a household full of children back then. BTW, I’ve also noticed that nobody forgets their first phone number and everyone remembers the phone number of their friend early on in life. Perhaps no longer. Current phone numbers often resemble gene sequences in their length and complexity. Who’d want to remember one? Remember something that might come in useful instead, like pi.

• • •

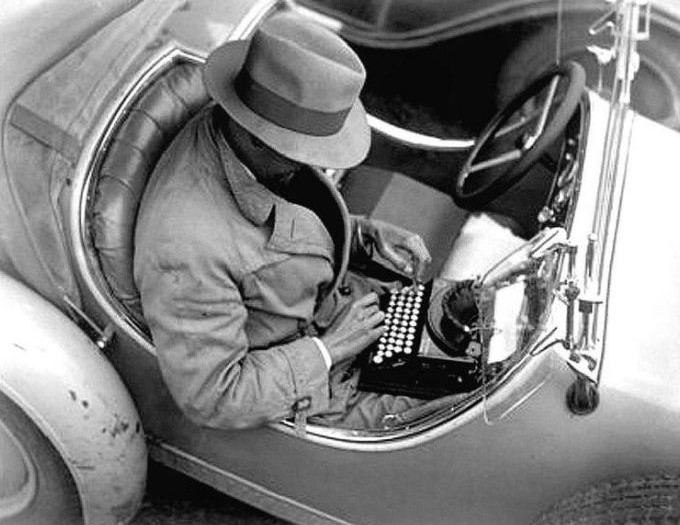

The central idea of this essay is that nobody speaks on the phone any more. A corollary of this is that people once did. While I have fond memories of phoning people (phone call + cigarette = heaven), I’d never want to go back to it. Why dawdle or waste time when a quick text or two can do the trick? This is a trick question because you have to ask yourself, what are you going to do with all the time you saved by texting and not phoning? The answer: send more texts.

• • •

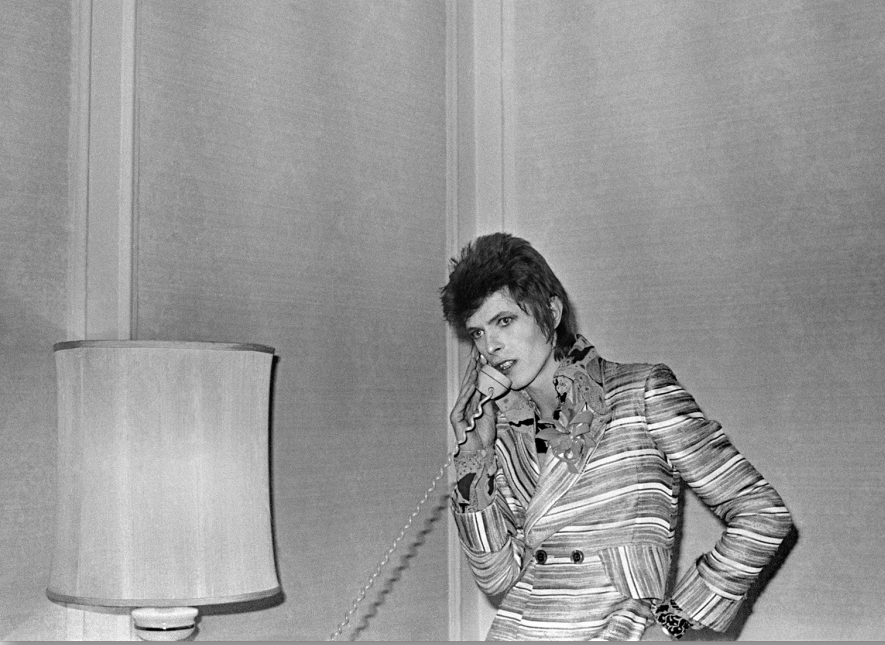

I remember having fun on the phone. Phones were once the only game in town. The experience of using one was far more charged than might now be imagined. But then, sometimes, only the phone will do. It was around midnight Pacific time when I found out David Bowie died; I spent the next three hours calling friends around the planet. Email didn’t cut it, so there you go.•