Usain Bolt runs really fast, for a human. Slow for a sheep.

Similarly, humans play chess really well for humans, but we’re inferior when competing on a wider playing field, when AI is introduced. That means we must redefine the way we view our role in the world.

Before the shift was complete and computers became our partners–our betters, in some unnerving ways–Garry Kasparov still had a fighting chance and so did you and I. At the end of the 1980s, the chess champion was able to stave off the onslaught, if only for a little while longer, when challenged by Deep Thought. From an article by Harold C. Schonberg in the October 23, 1989 New York Times:

“Yesterday Gary Kasparov, the world chess champion, played Deep Thought, the world computer chess champion, in a two-game match. He won both games handily, to nobody’s surprise, including his own.

Two hours before the start of the first game, held at the New York Academy of Art at 419 Lafayette Street in Manhattan, he held a conference for some 75 journalists representing news organizations all over the world. They were attracted to the event because of the possibility of an upset and the philosophical problems an upset would cause. Deep Thought, after all, has recently been beating grandmasters. Does this mean that the era of human chess supremacy is drawing to a close?

Yes, in the opinion of computer and chess experts.

The time is rapidly coming, all believe, when chess computers will be operating with a precision, rapidity and completeness of information that will far eclipse anything the human mind can do. In three to five years, Deep Thought will be succeeded by a computer with a thousand times its strength and rapidity. And computers scanning a million million positions a second are less than 10 years away. As for the creativity, intuition and brilliance of the great players, chess computers have already demonstrated that they can dream up moves that make even professionals gasp with admiration. It may be necessary to hold championship chess matches for computers and separate ones for humans. …

Mr. Kasparov, unlike many of the experts, was even doubtful that a computer could ever play with the imagination and creativity of a human, though he did look ahead to the next generation of computers and shuddered at what might be coming. Deep Thought can scan 720,000 positions a second. The creators of Deep Thought have developed plans for a machine that can scan a billion positions a second, and it may be ready in five years.

‘That means,’ grinned Mr. Kasparov, ‘that I can be champion for five more years.’ More seriously, he continued: ‘But I can’t visualize living with the knowledge that a computer is stronger than the human mind. I had to challenge Deep Thought for this match, to protect the human race.'”

_______________________________

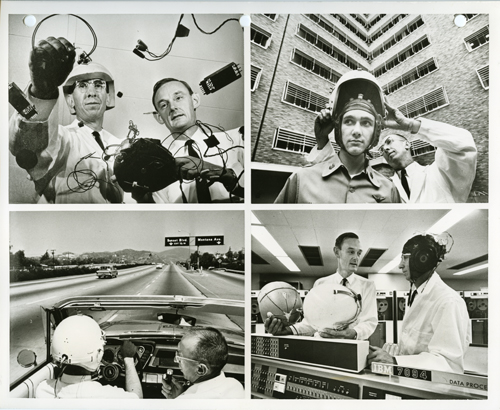

“What you have here is the phenomenon of how we define ourselves in relationship to the machine”: