I think of the era in America between the one wallpapered with newsprint (pre-1960) and the one given to smartphone updates (today), that time when TV news was predominant, as an age of delusion. That was when Newt Gingrich’s word games could work, when a screenshot of Willie Horton could win. It was an age of bullshit and manipulation. Why, an actor playing a part could become President, aided by Hallmark Card-level writers.

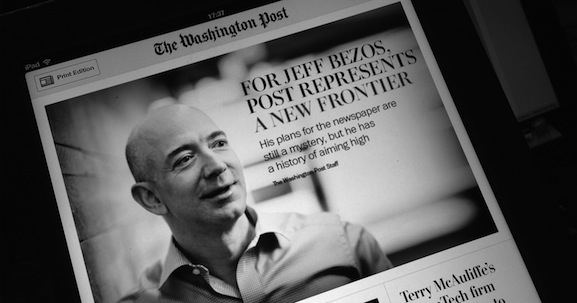

You’re free to feel less than sanguine about the transition, about the financial metrics of newsgathering and the threat it poses to less-profitable but vital journalism (as I sometimes am), but I will choose the deluge of information we get now to centralized media when far fewer had far greater control of the flow. People seem to get bamboozled much less now. Let it rain, I say. Let it pour. Let us swim together in the flood.

Anyhow, we always romanticized the wrong part of the newspaper. It wasn’t great because of the print. I mean, what’s so important about a lousy, crummy newspaper?

From “The Golden Age of Journalism?” a wonderful TomDispatch essay by Tom Engelhardt about the downfall of one type of news and the thing that has supplanted it:

“In so many ways, it’s been, and continues to be, a sad, even horrific, tale of loss. (A similar tale of woe involves the printed book. It’s only advantage: there were no ads to flee the premises, but it suffered nonetheless — already largely crowded out of the newspaper as a non-revenue producer and out of consciousness by a blitz of new ways of reading and being entertained. And I say that as someone who has spent most of his life as an editor of print books.) The keening and mourning about the fall of print journalism has gone on for years. It’s a development that represents — depending on who’s telling the story — the end of an age, the fall of all standards, or the loss of civic spirit and the sort of investigative coverage that might keep a few more politicians and corporate heads honest, and so forth and so on.

Let’s admit that the sins of the Internet are legion and well-known: the massive programs of government surveillance it enables; the corporate surveillance it ensures; the loss of privacy it encourages; the flamers and trolls it births; the conspiracy theorists, angry men, and strange characters to whom it gives a seemingly endless moment in the sun; and the way, among other things, it tends to sort like and like together in a self-reinforcing loop of opinion. Yes, yes, it’s all true, all unnerving, all terrible.

As the editor of TomDispatch.com, I’ve spent the last decade-plus plunged into just that world, often with people half my age or younger. I don’t tweet. I don’t have a Kindle or the equivalent. I don’t even have a smart phone or a tablet of any sort. When something — anything — goes wrong with my computer I feel like a doomed figure in an alien universe, wish for the last machine I understood (a typewriter), and then throw myself on the mercy of my daughter.

I’ve been overwhelmed, especially at the height of the Bush years, by cookie-cutter hate email — sometimes scores or hundreds of them at a time — of a sort that would make your skin crawl. I’ve been threatened. I’ve repeatedly received “critical” (and abusive) emails, blasts of red hot anger that would startle anyone, because the Internet, so my experience tells me, loosens inhibitions, wipes out taboos, and encourages a sense of anonymity that in the older world of print, letters, or face-to-face meetings would have been far less likely to take center stage. I’ve seen plenty that’s disturbed me. So you’d think, given my age, my background, and my present life, that I, too, might be in mourning for everything that’s going, going, gone, everything we’ve lost.

But I have to admit it: I have another feeling that, at a purely personal level, outweighs all of the above. In terms of journalism, of expression, of voice, of fine reporting and superb writing, of a range of news, thoughts, views, perspectives, and opinions about places, worlds, and phenomena that I wouldn’t otherwise have known about, there has never been an experimental moment like this. I’m in awe. Despite everything, despite every malign purpose to which the Internet is being put, I consider it a wonder of our age. Yes, perhaps it is the age from hell for traditional reporters (and editors) working double-time, online and off, for newspapers that are crumbling, but for readers, can there be any doubt that now, not the 1840s or the 1930s or the 1960s, is the golden age of journalism?

Think of it as the upbeat twin of NSA surveillance.“•