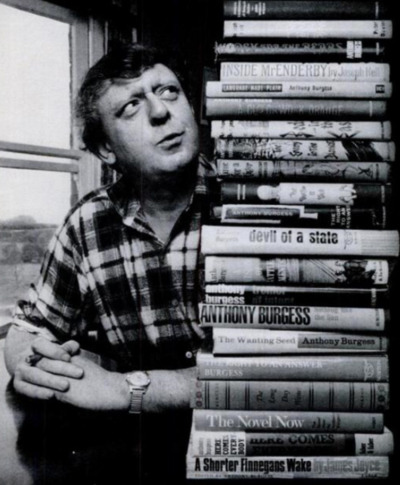

Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom, who thinks the sky may be fake or falling, has a new title, Superintelligence, which is about the Singularlity, out later this year. An excerpt from Bookseller about it, and then a passage from a 2007 New York Times article in which I first encountered Bostrom’s version of our world as a computer simulation.

_________________________

From Bookseller:

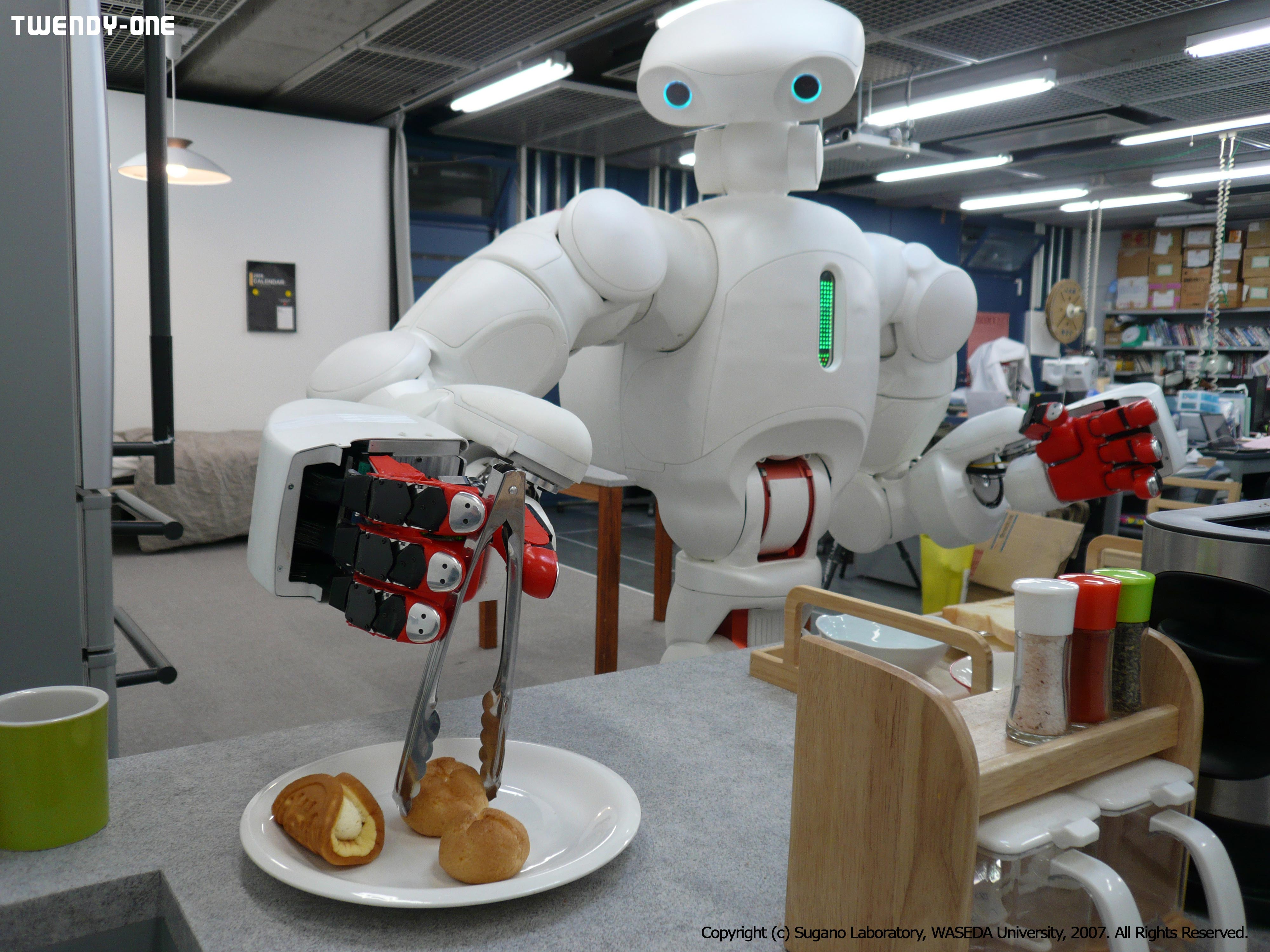

“’Everyone wonders when we’ll create a machine that’s as smart as us—or maybe just a little bit smarter than us. What people can fail to realise is that’s not the end of the process, rather [it’s] the beginning,’ [Oxford University Press science publisher Keith] Mansfield commented. ‘The smart machine will be capable of improving itself, becoming smarter still. Very quickly, we may see an intelligence explosion, with humanity left far behind.’

Just as the fate of gorillas now depends more on humans than on gorillas themselves, so the fate of our species would come to depend on the actions of machine superintelligence, Bostrom’s book will argue.”

_________________________

From “Our Lives, Controlled From Some Guy’s Couch,” by John Tierney:

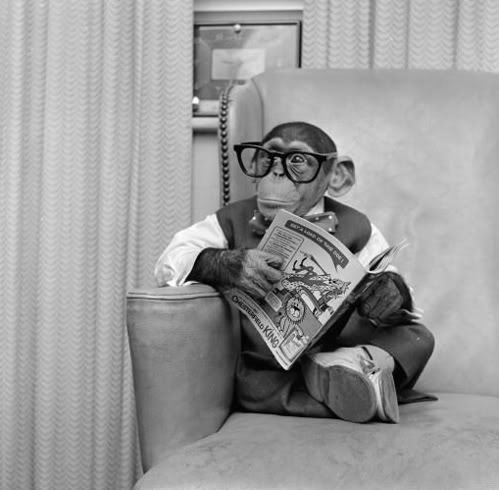

“Dr. Bostrom assumes that technological advances could produce a computer with more processing power than all the brains in the world, and that advanced humans, or ‘posthumans,’ could run ‘ancestor simulations’ of their evolutionary history by creating virtual worlds inhabited by virtual people with fully developed virtual nervous systems.

Some computer experts have projected, based on trends in processing power, that we will have such a computer by the middle of this century, but it doesn’t matter for Dr. Bostrom’s argument whether it takes 50 years or 5 million years. If civilization survived long enough to reach that stage, and if the posthumans were to run lots of simulations for research purposes or entertainment, then the number of virtual ancestors they created would be vastly greater than the number of real ancestors.

There would be no way for any of these ancestors to know for sure whether they were virtual or real, because the sights and feelings they’d experience would be indistinguishable. But since there would be so many more virtual ancestors, any individual could figure that the odds made it nearly certain that he or she was living in a virtual world.

The math and the logic are inexorable once you assume that lots of simulations are being run. But there are a couple of alternative hypotheses, as Dr. Bostrom points out. One is that civilization never attains the technology to run simulations (perhaps because it self-destructs before reaching that stage). The other hypothesis is that posthumans decide not to run the simulations.

‘This kind of posthuman might have other ways of having fun, like stimulating their pleasure centers directly,’ Dr. Bostrom says. ‘Maybe they wouldn’t need to do simulations for scientific reasons because they’d have better methodologies for understanding their past. It’s quite possible they would have moral prohibitions against simulating people, although the fact that something is immoral doesn’t mean it won’t happen.’

Dr. Bostrom doesn’t pretend to know which of these hypotheses is more likely, but he thinks none of them can be ruled out.”