Internet cafes will not make you dumber. (Image by Phallus Nocturne.)

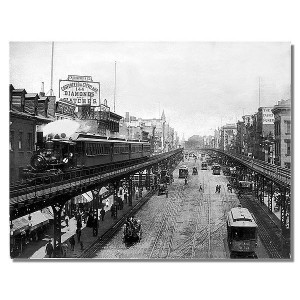

When I was growing up in my working-class neighborhood in Queens, there wasn’t a single bookstore in the community during my entire childhood. Not one. There were candy stores where you could get a paper or a magazine and a couple of small, semi-stocked libraries, but it was difficult for a kid with a curious mind to grow up in that environment. You had to take a train to Manhattan just to get a hold of something with hard covers to read. I always felt like there was information somewhere, but I didn’t know where it was.

You know what would have leveled the playing field? The Internet. It didn’t exist then, but it does now, and it has the potential to connect any reader in the world to any book they want. You can find out about any university, look up any word and read an incredible array of great writing wherever there’s a wi-fi connection. That doesn’t mean everyone will use the medium to improve themselves, but it’s pretty hard to avoid doing so. The Internet is democratizing and despite what the hand-wringers say, it’s made our knowledge deeper and stronger.

That’s why I bristle when I hear how the Internet is destroying the literary mind and damaging our memories. If it seems like our memories are failing more often than they used to, that’s because we have so much more information at our fingertips. Ultimately, that’s a good thing.

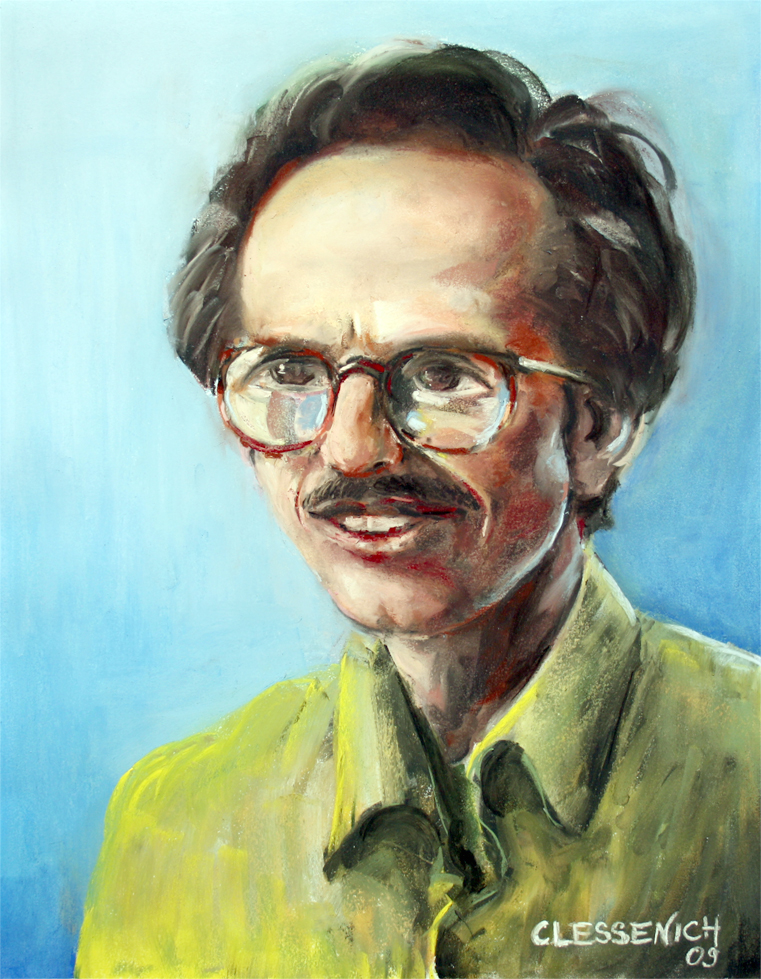

One person who agrees with me is Steven Pinker. Pinker is a psychology professor at Harvard who’s best known for his book, The Stuff of Thought. In an article on Edge, he addresses concerns about what the Internet is doing to our brains. An excerpt:

“New forms of media have always caused moral panics: the printing press, newspapers, paperbacks and television were all once denounced as threats to their consumers’ brainpower and moral fiber.

So too with electronic technologies. PowerPoint, we’re told, is reducing discourse to bullet points. Search engines lower our intelligence, encouraging us to skim on the surface of knowledge rather than dive to its depths. Twitter is shrinking our attention spans.

But such panics often fail basic reality checks. When comic books were accused of turning juveniles into delinquents in the 1950s, crime was falling to record lows, just as the denunciations of video games in the 1990s coincided with the great American crime decline. The decades of television, transistor radios and rock videos were also decades in which I.Q. scores rose continuously.

For a reality check today, take the state of science, which demands high levels of brainwork and is measured by clear benchmarks of discovery. These days scientists are never far from their e-mail, rarely touch paper and cannot lecture without PowerPoint. If electronic media were hazardous to intelligence, the quality of science would be plummeting. Yet discoveries are multiplying like fruit flies, and progress is dizzying.”