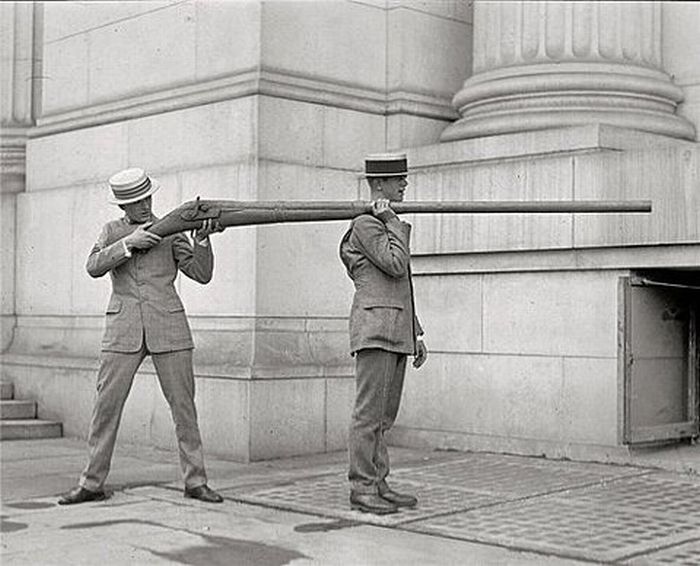

The anarchy of the Internet will be unloosed into the physical world more and more as we move forward, with 3D printers and gene-editing kits and the like. That will be mostly good, but what if just a little bit of it is catastrophically bad? Assault rifles won’t be the only untraceable weapons to fall into the wrong hands.

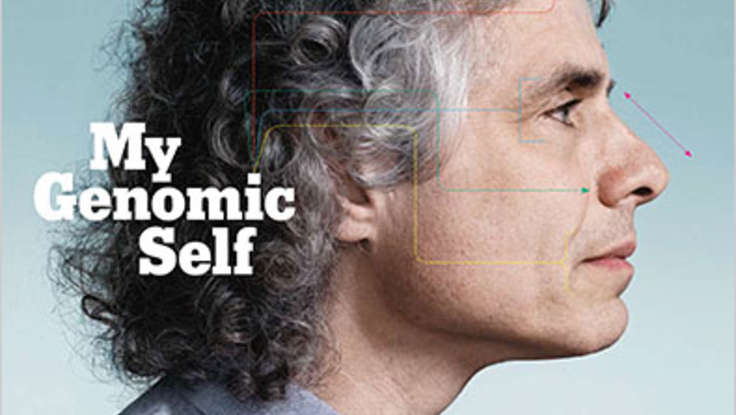

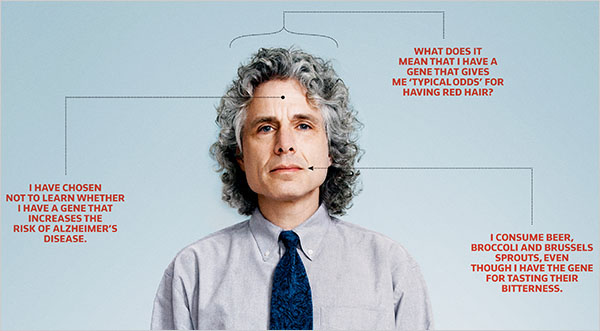

In a thought-provoking IEEE Spectrum essay, Phil Torres wonders if positivists like Steven Pinker aren’t missing a small explosive truth while admiring the hopeful big-picture data. An excerpt:

If one actually looks at the statistics, the world is steadily becoming more peaceful. This is the conclusion of Steven Pinker’s monumental 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature, as well as Michael Shermer’s excellent 2015 follow-up The Moral Arc (essentially a “sequel” of Pinker’s tome). The surprising, counterintuitive fact is that the global prevalence of genocides, homicides, infanticide, domestic violence, and violence against children is declining, while democratization, women’s rights, gay rights, and even animals rights are on the rise. The probability that any one of us dies at the hands of another human being rather than from natural causes is perhaps the lowest it’s ever been in human history, even before the Neolithic Revolution. If that’s not Progress with a capital ‘p’, then I don’t know what is.

The oceanic evidence that Pinker and Shermer present is robust and cogent. Yet I think there’s another story to tell — one that hints at a possible future marked by unprecedented human suffering, global catastrophes, and even our extinction. The fact is that while the enterprise of human civilization has been making significant ethical strides forward in multiple domains, a range of emerging technologies are, by nearly all accounts, poised to introduce brand new existential risks never before encountered by our species

…

the most worrisome threats are not merely anthropogenic, they’re technogenic. They arise from the fact that advanced technologies are (a) dual-use in nature, meaning that they can be employed for both benevolent and nefarious purposes; (b) becoming more powerful, thereby enabling humans to manipulate and rearrange the physical world in new ways; and (c) in some cases, becoming more accessible to small groups, including, at the limit, single individuals. This is notable because just as there are many more terrorist groups than rogue nations in the world, there are far more deranged psychopaths than terrorist groups. Thus, the number of possible offenders armed with catastrophic weaponry is likely to increase significantly in the future.

It’s not clear how the trends that Pinker and Shermer identify could save us from this situation. Even if 99% of human beings in the year 02100 were peaceable, the remaining 1% could find themselves with enough technological power at their fingertips to initiate a disaster of global proportions. Or, forget 1% — what about a single individual with a death wish for humanity, or a single apocalyptic group hoping to engage in the ultimate mass suicide event? In a world cluttered with doomsday machines, exactly how long could we expect to survive?•