Trump hit the iceberg today and Sarah Huckabee Sanders is the band that played on.

Whether American democracy itself winds up collateral damage to the hulking political scandal that’s just begun taking on water—the biggest breach of ethics in the history of American governance—is still TBD. A constitutional crisis is as likely than anything else. But it’s important to remember that while Trump was the absolute worse roll of the dice (and loaded dice, at that), it was the house that was crooked. Nearly 63 million citizens cast a ballot for a bigoted, incompetent, money-laundering game-show host, and that’s a deep indictment on many of our systems—political, educational, media, etc. Even if we remain standing during Trump’s ignominious fall, we’ll continue wobbling on the precipice unless some deep fixes are enacted.

· · ·

It’s an American tradition to rehabilitate crooks and liars of years gone by who are no longer in possession of power to do grave damage, making them seem harmless in their dotage: Nixon, Kissinger, Goldwater, etc. The latter politico, the architect of society-busting Reagonomics, was sometimes seated next to Jay Leno in the 1990s, apparently humbled as he shared anecdotes. It’s not likely he’d changed; we’d just forgotten.

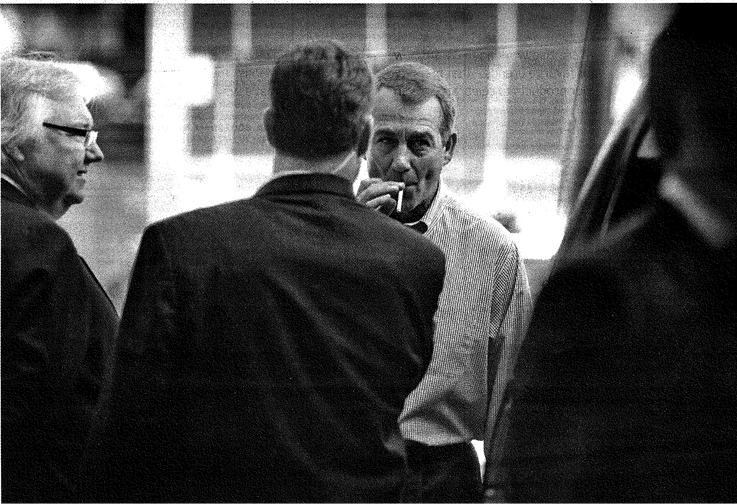

The same tendency is at play with more recent goats, including George W. Bush, an interesting outsider artist who broke the world through incompetence and dishonesty, and John Boehner, the former teary-eyed and often destructive Speaker, who is his retirement is willing to say shitty things about shitty Republicans in between Marlboro drags and coughing fits. Some in the media and populace applaud because he was never as bad as Trump, but let’s recall that he was one of the agents who led to our current calamity.

From Tim Alberta’s fascinating Politico profile about Boehner at rest (or as close to it as he can manage):

A bipartisan group of eight senators had crafted a comprehensive immigration bill that appeared to have support in the House GOP. But in June, when the Senate passed it—68 to 32, with 14 Republicans voting yes—House members found themselves under siege from constituents and conservative groups. The fatal flaw: It provided a path to citizenship, albeit a winding one, for people in the country illegally. Many conservatives could support a path to legal status but not citizenship; Democrats, on the other hand, essentially took a citizenship-or-nothing approach. Boehner was boxed in: He wanted immigration reform, and personally didn’t mind citizenship—especially for minors brought to the U.S. unwittingly. But putting the bill on the floor meant it might pass into law with perhaps as few as 40 or 50 of his members voting yes. Conservatives would never forgive him for overruling the vast majority of his membership. Looking back, Boehner says not solving immigration is his second-biggest regret, and he blames Obama for “setting the field on fire.” But the former speaker doesn’t mention the nativist voices in his own party that came to dominate the debate, foreshadowing the presidential campaign three years later. Ultimately, the speaker’s immigration quandary boiled down to a choice between protecting his right flank and doing what he thought was right for the country—and Boehner chose the former.

It wasn’t the only time. That summer, conservatives were also getting an earful about the Obamacare exchanges opening on October 1. House Republicans had voted repeatedly to repeal the law but the Senate refused to act, and their constituents, justifiably, wanted to know why Obamacare still existed when they had been promised otherwise. “Somehow, out on the campaign trail, the representation was made that you could beat President Obama into submission to sign a repeal of the law with his name on it,” Cantor says. “And that’s where things got, I think, disconnected from reality.” (In Ohio, listening to his pals groan about Obamacare, Boehner explains why his former colleagues haven’t repealed it: “Their gonads shriveled up when they learned this vote was for real.”)

Republicans’ penchant for overpromising and underdelivering would ultimately enable the ascent of Donald Trump, who positioned himself as a results-oriented outsider who would deliver where politicians had failed. In the shorter term, it invited something less dramatic: a government shutdown. Eager to demonstrate that all options were being exhausted to defeat Obamacare, Ted Cruz in the Senate and conservatives in the House concocted a plan: Because the government needed new funding on October 1, the same day the exchanges would open, they would propose funding the rest of the federal government—while defunding Obamacare.

Boehner objected. Not only would Democrats never go for it; Republicans would be blamed for the resulting government shutdown. “I told them, ‘Don’t do this. It’s crazy. The president, the vice president, Reid, Pelosi, they’re all sitting there with the biggest shit-eating grins on their faces that you’ve ever seen, because they can’t believe we’re this fucking stupid.’” (Boehner, at one point, surprises me by saying he’s proud of Cruz—whom he once called “Lucifer in the flesh”—for acting responsibly in 2017. Do you feel badly about calling him Lucifer, I ask? “No!” Boehner snorts. “He’s the most miserable son of a bitch I’ve ever had to work with.”)

After railing against the defund strategy, however, Boehner surveyed his conference and realized it was a fight many members wanted—and some needed. Yielding, he joined them in the trenches, abandoning his obligations of governance in hopes of strengthening his standing in the party. But the 17-day shutdown proved costly. Watching as Republicans got butchered in nationwide polling, the speaker finally called a meeting to inform members that they would vote to reopen the government and raise the debt ceiling. “I get a standing ovation,” Boehner says. “I’m thinking, ‘This place is irrational.’”•