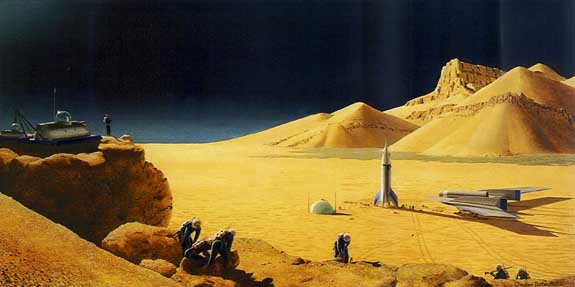

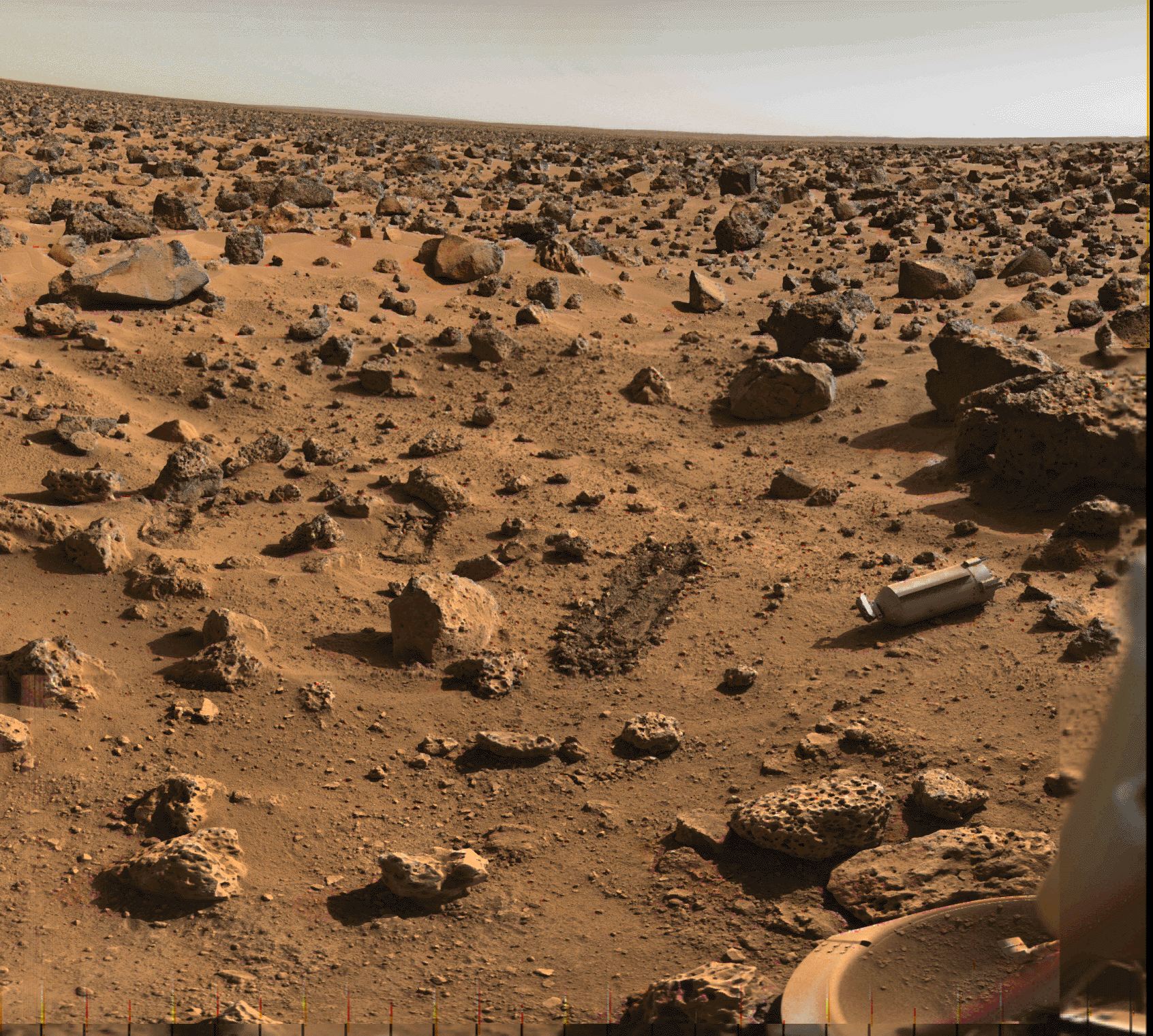

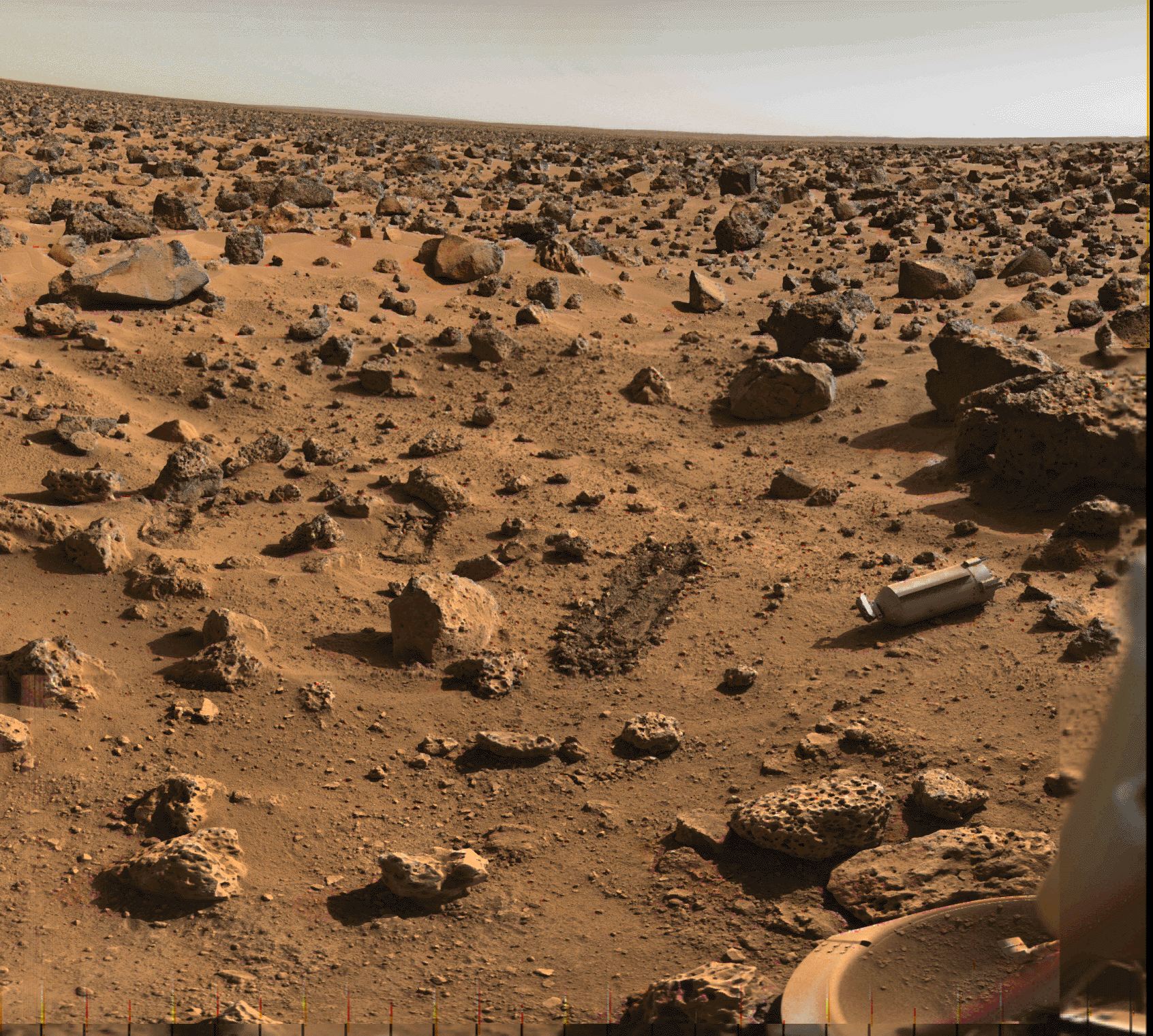

That excellent Ross Andersen is back with a new Aeon essay, this one a look at the grand hedge being made by Elon Musk who seeks to populate Mars in case of human extinction on Earth. The technologist estimates it will take a million “Martians” to ensure the species’ survival in event of famine or plague or technological apocalypse on our home planet. But should we be rushing into the unknown while we’re still in our technological infancy, driven to haste by irritation over NASA’s perplexing dormancy? Or is it already very late? As is usual in Andersen’s explorations, the subject heads off in deep and mysterious directions. An excerpt:

“Musk told me he often thinks about the mysterious absence of intelligent life in the observable Universe. Humans have yet to undertake an exhaustive, or even vigorous, search for extraterrestrial intelligence, of course. But we have gone a great deal further than a casual glance skyward. For more than 50 years, we have trained radio telescopes on nearby stars, hoping to detect an electromagnetic signal, a beacon beamed across the abyss. We have searched for sentry probes in our solar system, and we have examined local stars for evidence of alien engineering. Soon, we will begin looking for synthetic pollutants in the atmospheres of distant planets, and asteroid belts with missing metals, which might suggest mining activity.

The failure of these searches is mysterious, because human intelligence should not be special. Ever since the age of Copernicus, we have been told that we occupy a uniform Universe, a weblike structure stretching for tens of billions of light years, its every strand studded with starry discs, rich with planets and moons made from the same material as us. If nature obeys identical laws everywhere, then surely these vast reaches contain many cauldrons where energy is stirred into water and rock, until the three mix magically into life. And surely some of these places nurture those first fragile cells, until they evolve into intelligent creatures that band together to form civilisations, with the foresight and staying power to build starships.

‘At our current rate of technological growth, humanity is on a path to be godlike in its capabilities,’ Musk told me. ‘You could bicycle to Alpha Centauri in a few hundred thousand years, and that’s nothing on an evolutionary scale. If an advanced civilisation existed at any place in this galaxy, at any point in the past 13.8 billion years, why isn’t it everywhere? Even if it moved slowly, it would only need something like .01 per cent of the Universe’s lifespan to be everywhere. So why isn’t it?’

Life’s early emergence on Earth, only half a billion years after the planet coalesced and cooled, suggests that microbes will arise wherever Earthlike conditions obtain. But even if every rocky planet were slick with unicellular slime, it wouldn’t follow that intelligent life is ubiquitous. Evolution is endlessly inventive, but it seems to feel its way toward certain features, like wings and eyes, which evolved independently on several branches of life’s tree. So far, technological intelligence has sprouted only from one twig. It’s possible that we are merely the first in a great wave of species that will take up tool-making and language. But it’s also possible that intelligence just isn’t one of natural selection’s preferred modules. We might think of ourselves as nature’s pinnacle, the inevitable endpoint of evolution, but beings like us could be too rare to ever encounter one another. Or we could be the ultimate cosmic outliers, lone minds in a Universe that stretches to infinity.

Musk has a more sinister theory. ‘The absence of any noticeable life may be an argument in favour of us being in a simulation,’ he told me. ‘Like when you’re playing an adventure game, and you can see the stars in the background, but you can’t ever get there. If it’s not a simulation, then maybe we’re in a lab and there’s some advanced alien civilisation that’s just watching how we develop, out of curiosity, like mould in a petri dish.’ Musk flipped through a few more possibilities, each packing a deeper existential chill than the last, until finally he came around to the import of it all. ‘If you look at our current technology level, something strange has to happen to civilisations, and I mean strange in a bad way,’ he said. ‘And it could be that there are a whole lot of dead, one-planet civilisations.’”