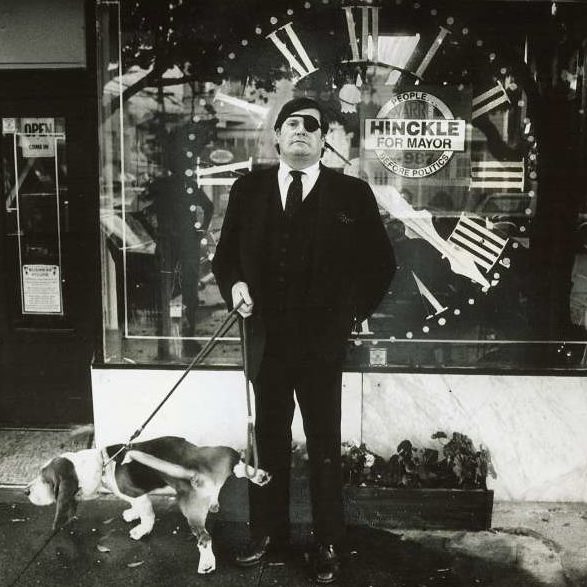

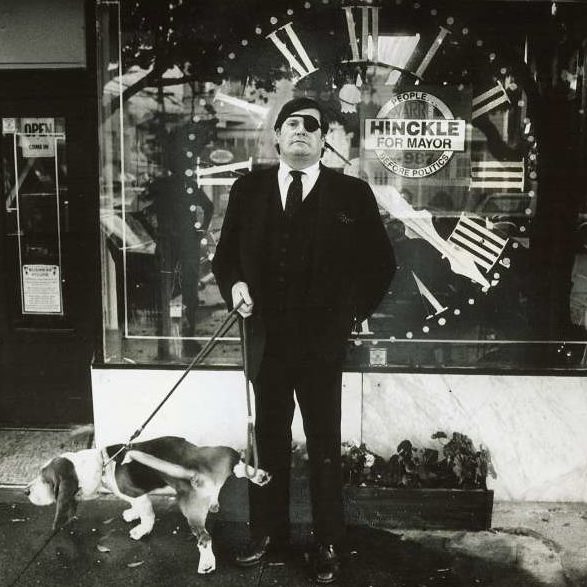

If you want to comprehend the often-disquieting zeitgeist of the Sixties and Seventies, you could do far worse than read back issues of Ramparts magazine, which, under Warren Hinckle’s gonzo editorial guidance, served up the alternative culture without ever watering it down. The journalist just died, and below is his NYT obituary penned by William Grimes, followed by a few of the best articles he wrote and published at Ramparts.

From Grimes:

Warren Hinckle, the flamboyant editor who made Ramparts magazine a powerful national voice for the radical left in the 1960s and later by championing the work of Hunter S. Thompson and helping introduce the no-holds-barred reporting style known as gonzo journalism, died on Thursday. He was 77.

The cause was complications of pneumonia, his daughter Pia Hinckle said.

Ramparts was a small-circulation quarterly for liberal Roman Catholics when Mr. Hinckle began writing for and promoting it in the early 1960s. A born provocateur with a keen sense of public relations, he took over as the executive editor in 1964 and immediately set about transforming Ramparts from a sleepy intellectual journal to a slickly produced, crusading political magazine that galvanized the American left.

With cover art and eye-catching headlines reminiscent of mainstream magazines like Esquire, Ramparts aimed to deliver “a bomb in every issue,” as Time magazine once put it. It looked at Cardinal Francis Spellman’s involvement in promoting American involvement in Vietnam and the Central Intelligence Agency’s financing of a wide variety of cultural organizations.

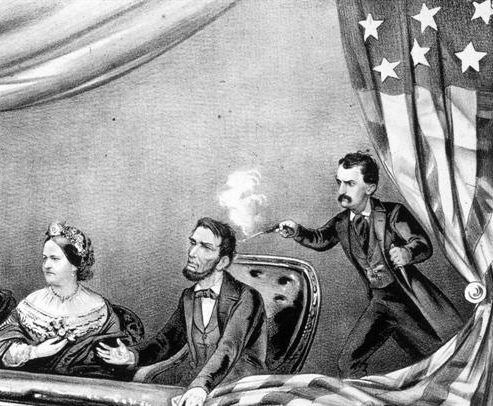

It published Che Guevara’s diaries, with a long introduction by Fidel Castro; Eldridge Cleaver’s letters from prison; and some of the wilder conspiracy theories surrounding the Kennedy assassination. The magazine’s photo essay in January 1967 showing the injuries inflicted on Vietnamese children by American bombs helped convince the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to take a public stand against the war.

The covers became countercultural classics: an illustration depicting Ho Chi Minh, the Communist leader of North Vietnam, as Washington crossing the Delaware; a photograph of four hands, belonging to the magazine’s top editors, holding up draft cards that had been set on fire.•

“Rather Than Write, I Will Ride Buses, Study The Insides Of Jails, And See What Goes On”

From “The Social History of the Hippies,” Warren Hinckle’s 1967 Ramparts article about those who tuned in, turned on and dropped out, a segment on writer Ken Kesey after his fall from grace with the younger longhhairs:

From “The Social History of the Hippies,” Warren Hinckle’s 1967 Ramparts article about those who tuned in, turned on and dropped out, a segment on writer Ken Kesey after his fall from grace with the younger longhhairs:

HERE WASN’T MUCH DOING on late afternoon television, and the Merry Pranksters were a little restless. A few were turning on; one Prankster amused himself squirting his friends with a yellow plastic watergun; another staggered into the living room, exhausted from peddling a bicycle in ever-diminishing circles in the middle of the street. They were all waiting, quite patiently, for dinner, which the Chief was whipping up himself. It was a curry, the recipe of no doubt cabalistic origin. Kesey evidently took his cooking seriously, because he stood guard by the pot for an hour and a half, stirring, concentrating on the little clock on the stove that didn’t work.

There you have a slice of domestic life, February 1967, from the swish Marin County home of Attorney Brian Rohan. As might be surmised, Rohan is Kesey’s attorney, and the novelist and his aides de camp had parked their bus outside for the duration. The duration might last a long time, because Kesey has dropped out of the hippie scene. Some might say that he was pushed, because he fell, very hard, from favor among the hippies last year when he announced that he, Kesey, personally, was going to help reform the psychedelic scene. This sudden social conscience may have had something to do with beating a jail sentence on a compounded marijuana charge, but when Kesey obtained his freedom with instructions from the judge ‘to preach an anti-LSD warning to teenagers’ it was a little too much for the Haight-Ashbury set. Kesey, after all, was the man who had turned on the Hell’s Angels.

That was when the novelist was living in La Honda, a small community in the Skyline mountain range overgrown with trees and, after Kesey invited the Hell’s Angels to several house parties, overgrown with sheriff’s deputies. It was in this Sherwood Forest setting, after he had finished his second novel with LSD as his co-pilot, that Kesey inaugurated his band of Merry Pranksters (they have an official seal from the State of California incorporating them as “Intrepid Trips, Inc.”), painted the school bus in glow sock colors, announced he would write no more (“Rather than write, I will ride buses, study the insides of jails, and see what goes on”), and set up funtime housekeeping on a full-time basis with the Pranksters, his wife and their three small children (one confounding thing about Kesey is the amorphous quality of the personal relationships in his entourage—the several attractive women don’t seem, from the outside, to belong to any particular man; children are loved enough, but seem to be held in common).

When the Hell’s Angels rumbled by, Kesey welcomed them with LSD. “We’re in the same business. You break people’s bones, I break people’s heads,” he told them. The Angels seem to like the whole acid thing, because today they are a fairly constant act in the Haight-Ashbury show, while Kesey has abdicated his role as Scoutmaster to fledgling acid heads and exiled himself across the Bay.

This self-imposed Elba came about when Kesey sensed that the hippie community had soured on him. He had committed the one mortal sin in the hippie ethic: telling people what to do. “Get into a responsibility bag,” he urged some 400 friends attending a private Halloween party. Kesey hasn’t been seen much in the Haight-Ashbury since that night, and though the Diggers did succeed in getting him to attend the weekend discussion, it is doubtful they will succeed in getting the novelist involved in any serious effort to shape the Haight-Ashbury future. At 31, Ken Kesey is a hippie has-been.•

“I Found Myself Incarcerated In An Anonymity”

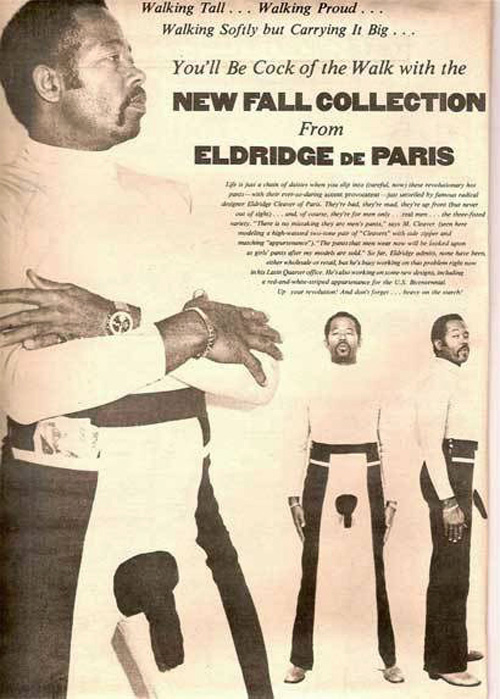

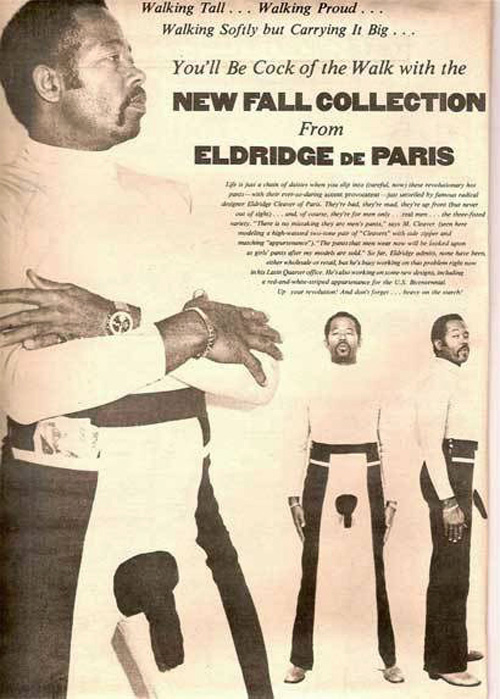

Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver was many things, and not all of them were good. But no one could deny he was a fascinating fashion designer. After fleeing the United States when charged with the attempted murder of police officers in Oakland in 1968, the revolutionary spent seven years hiding in a variety of foreign countries. A mostly forgotten part of his walkabout was Cleaver surfacing as a fashion designer in Paris at the very end of his exile. As shown in the print advertisement above, his so-called “penis pants” had an external sock attached so that a guy could wear his junk on the outside. I mean, just because your soul was on ice, that didn’t mean your dong had to be. Cucumber sales soared.

Cleaver penned an article about the early part of his life at large for Ramparts in 1969. An excerpt:

SO NOW IT IS OFFICIAL. I was starting to think that perhaps it never would be. For the past eight months, I’ve been scooting around the globe as a non-person, ducking into doorways at the sight of a camera, avoiding English-speaking people like the plague. I used so many names that my own was out of focus. I trained myself not to react if I heard the name Eldridge Cleaver called, and learned instead to respond naturally, spontaneously, to my cover names. Anyone who thinks this is easy to do should try it. For my part, I’m glad that it is over.

This morning we held a press conference, thus putting an end to all the hocus-pocus. Two days ago, the Algerian government announced that I had arrived here to participate in the historic First Pan-African Cultural Festival. After that, there was no longer any reason not to reach for the telephone and call home, so the first thing I did was to call my mother in Los Angeles. ‘Boy, where are you at?’ she asked. It sounded as though she expected me to answer, ‘Right around the corner, mom,’ or ‘Up here in San Francisco,’ so that when I said I was in Africa, in Algeria, it was clear that her mind was blown, for her response was, “Africa? You can’t make no phone call from Africa!” That’s my mom. She doesn’t relate to all this shit about phone calls across the ocean when there are no phone poles. She has both her feet on the ground, and it is clear that she intends to keep them there.

It is clear to me now that there are forms of imprisonment other than the kind I left Babylon to avoid, for immediately upon splitting that scene I found myself incarcerated in an anonymity, the walls of which were every bit as thick as those of Folsom Prison. I discovered, to my surprise, that it is impossible to hold a decent conversation without making frequent references to one’s past. So I found myself creating personal histories spontaneously, off the top of my head, and I felt bad about that because I know that I left many people standing around scratching their heads. The shit that I had to run down to them just didn’t add up.

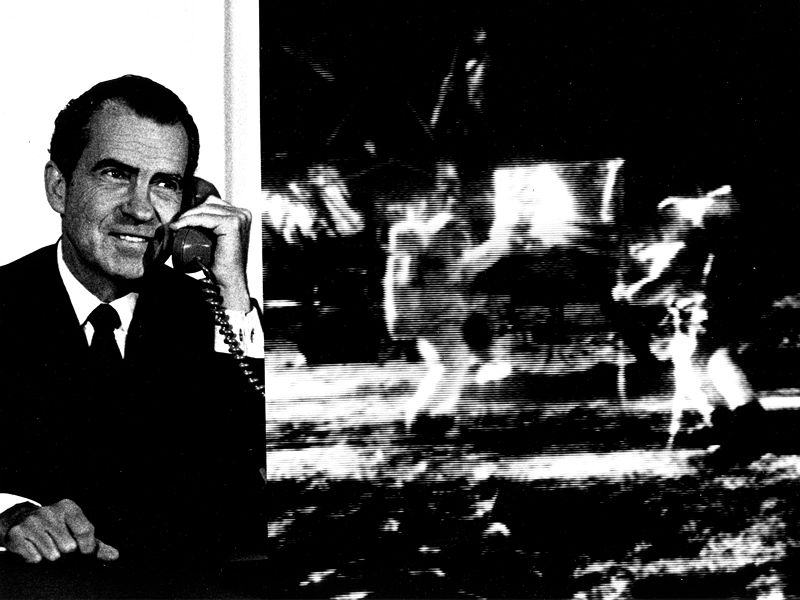

Now all that is over. So what? What has really changed? Alioto is still crazy and mayor, Ronald Reagan is still Mickey Mouse, Nixon is in the White House and the McClellan Committee is investigating the Black Panther Party. And Huey P. Newton is still in prison. I cannot make light of this shit because it is getting deeper. And here we are in Algeria. What is a cat from Arkansas, who calls San Francisco home, doing in Algeria? And listen to Kathleen behind me talking over the telephone in French. With a little loosening of the will, I could easily flip out right now!•

“Lenny Was Called A ‘Sick Comic,’ Though He Insisted That It Was Society Which Was Sick And Not Him”

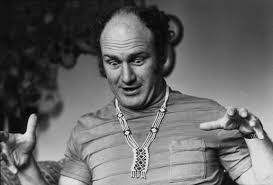

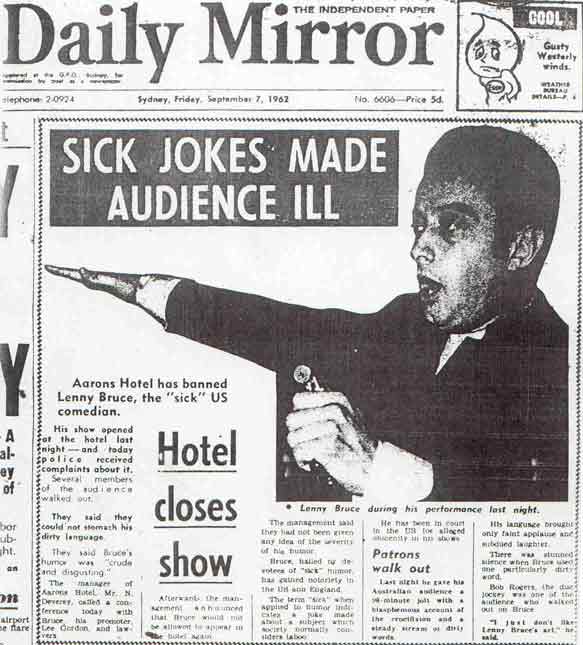

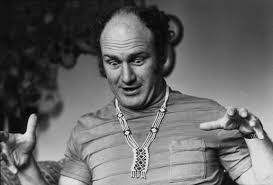

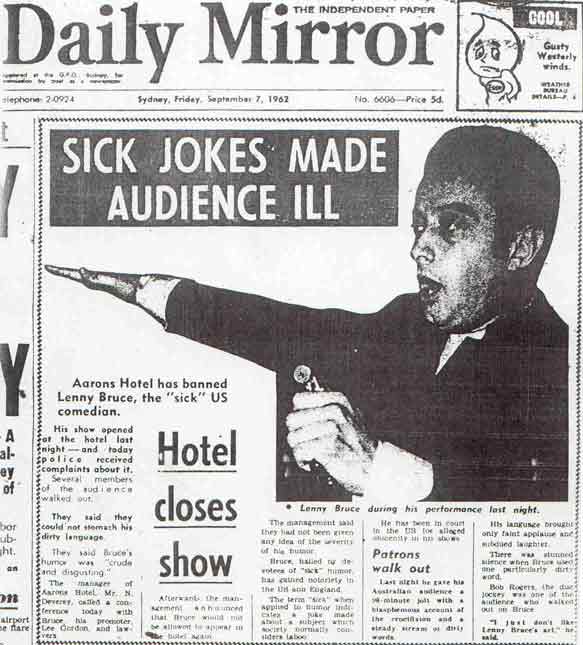

Lenny Bruce understood there are few things more obscene than a society full of people making believe that obscene things never happened, since pretending and suppressing and hiding and shushing allows true evil to flourish. The opening of Ralph J. Gleason’s emotional 1966 obituary of Bruce in Ramparts:

WHEN THE BODY OF LEONARD SCHNEIDER—stage name Lenny Bruce—was found on the floor of his Hollywood hills home on August 3, the Los Angeles police immediately announced that the victim had died of an overdose of a narcotic, probably heroin.

The press and TV and radio of the nation—the mass media—immediately seized upon this statement and headlined it from coast to coast, never questioning the miracle of instant diagnosis by a layman.

The medical report the next day, however, admitted that the cause of death was unknown and the analysis ‘inconclusive.’ But, as is the way with the mass media, news grows old, and the truth never quite catches up. Lenny Bruce didn’t die of an overdose of heroin. God alone knows what he did die of.

It is ritualistically fitting that he should be the victim, in the end, of distorted news, police malignment and the final irony—being buried with an orthodox Hebrew service, after years of satirizing organized religion. But first, in a sinister evocation of Orwell and Kafka and Greek tragedy, he had to be tortured, the record twisted, and the files rewritten until his death became a relief.

Lenny was called a “sick comic,” though he insisted that it was society which was sick and not him. He was called a ‘dirty comic’ though he never used a word you and I have not heard since our childhood. His tangles with the law over the use of these words and his arrests on narcotics charges were the only two things that the public really knew about him. Mass media saw to that.

When he was in Mission General Hospital in San Francisco, the hospital announced he had screamed such obscenities that the nurses refused to work in the room with him, so they taped his mouth shut with adhesive tape. The newspapers revelled in this and he was shown on TV, his mouth taped and his eyes rolling in protest, being wheeled into the examining room. Words that nurses never heard?

What new phrases he must have invented that day, what priceless epiphanies lost to history now forever. Once, in a particularly poignant discussion of obscenity on stage, Bruce said, “If the titty is pretty it’s dirty, but not if it’s bloody and maimed . . . that’s why you never see atrocity photos at obscenity trials.” He used to point out, too, that the people who watched the killing of the Genovese girl in Brooklyn and who didn’t interfere or call a cop would have been quick to do both if it had been a couple making love. “A true definition of obscenity,” he said, “would be to sing about pork outside a synagogue.”

Bruce found infinity in the grain of sand of obscenity. From it he took off on the fabric which keeps all our lives together. “If something about the human body disgusts you,” he said, “complain to the manufacturer.” He was one of those who, in Hebbel’s expression, “have disturbed the world’s sleep.” And he could not be forgiven.•

“The Real And The Unreal In A Sense Became Totally Confused”

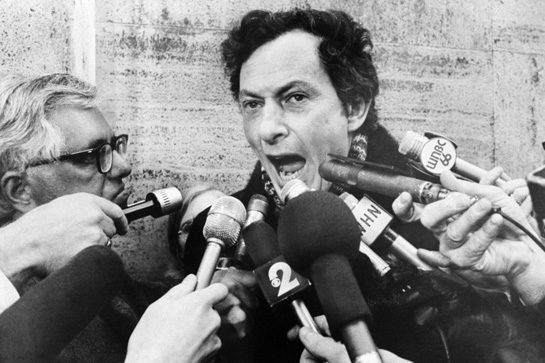

I’m a little obsessed with Clifford Irving, the writer who in 1970 accepted a million-dollar check for his authorized biography of the reclusive millionaire Howard Hughes. One problem: Hughes knew nothing of the book. The author was trying to pass off a fake and pocket a huge payday, and just as fascinating as the ruse was Irving doggedly sticking to his story even after the whole thing fell apart spectacularly. It was a literary scandal of Madoff-ian proportions, and a case study in extreme psychological behavior.

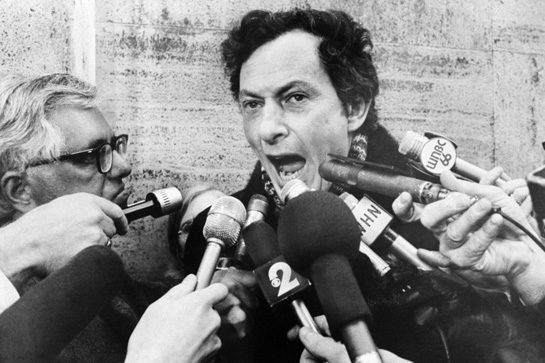

In 1972, as Irving was about to serve a stretch in prison for fraud, Ramparts magazine assigned Abbie Hoffman to do a Q&A with the trickster. An excerpt from “How Clifford Irving Stole That Book“:

Abbie Hoffman:

Did you ever get the idea, once the authenticity was questioned, of publishing it as a work of fiction? Would that have been really possible?

Clifford Irving:

You mean since recent events?

Abbie Hoffman:

Yeah.

Clifford Irving:

Oh, yeah, I still would like to have the book published. I think it’s the best novel I’ve ever written and it could easily be turned into a novel. It could also be published as is, provided libelous passages were taken out of it and provided that it stated very clearly that it’s a bogus autobiography of Howard Hughes. There is a court ruUng on it. As we understand it the court has given us permission to publish part or all of the book, provided that it’s made perfectly clear that it doesn’t purport to be genuine.

Abbie Hoffman:

I thought a funny incident occurred at Germaine Greer’s press party when you were introduced to Chief Red Fox. Could you talk about that a little?

Clifford Irving:

I went to this cocktail party. I was dragged along by Beverly Loo and Robert Stewart. I hate those damn cocktail parties but I had nothing to do and I wanted to meet Germaine Greer ’cause I heard she was six feet tall. But she was far more interested in talking to women’s liberation people and I stood around like a dope for awhile until I saw this beautiful old man in a corner. I asked about him and was told that’s Chief Red Fox, a 101-year-old Sioux Indian chief, and I said, ‘Beautiful, I’ve got to meet him.’ And I sat at his feet for an hour or two, talked to him, and he was a marvelous old man. But the way he came on to me with the broad American accent and told me how he danced at supermarket openings and was on the Johnny Carson Show where he did a war dance to liven things up, also the way he talked about Indian history, made me a little leery and I thought, well, he’s great but he’s not a 101-year-old Sioux Indian chief. Despite the fact that he was decked out like a technicolor western with a war bonnet and greasepaint make-up. And I went up to Beverly Loo and said,’He’s a great man, Beverly, but he’s no more a 101-year-old Sioux Indian than you’re the Empress Loo of the Ming Dynasty. She got very uptight about that and said, ‘What do you mean? How dare you!’ and I decided not to upset her any further so I backed off. Then of course it turned out later that there were great doubts thrown on the veracity of his books and his identity as well. I don’t know if I really smelled it out but something was funny there. I think maybe I was thinking in terms of a hoax since I was involved with one, and Chief Red Fox seemed to fit right into the category.

Abbie Hoffman:

When incidents like that happened did you start to feel you were watching a movie being made about your life or that you were acting out some kind of movie role?

Clifford Irving:

Well, going through that year I often felt that it was a happening because we sometimes had control over events but so many things happened that were absurd. And after awhile—not that I saw myself as a movie star—I saw this whole thing developing as a script, a movie script which no one would ever buy because it was ridiculous, it couldn’t possibly happen. The real and the unreal in a sense became totally confused—not that I really thought I was writing the autobiography of Howard Hughes, although of course in the act of creation you have to believe to a certain extent, but when you stop work you don’t believe any more. I mean you know what you’re doing but all the events had such a quality of ludicrousness and fantasy and coincidence that reality did at times blend with unreality. I think for the publishers as well.•

“They Do Learn How To Read Too, But It Is A Secondary Discipline”

In a 1966 issue of Ramparts, writer Howard Gossage tried to explain the teachings of Marshall McLuhan, whose book from two years earlier, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, had announced him as a media star with a message. An excerpt:

McLuhan’s theory is that this is the first generation of the electronic age. He says they are different because the medium that controls their environment is not print — one thing at a time, one thing after another — as it has been for 500 years. It is television, which is everything happening at once, instantaneously, and enveloping.

A child who gets his environmental training on television— and very few nowadays do not — learns the same way any member of a pre-literate society learns: from the direct experience of his eyes and ears, without Gutenberg for a middle man. Of course they do learn how to read too, but it is a secondary discipline, not primary as it is with their elders. When it comes to shaping sensory perceptions, I’m afraid that Master Gutenberg just isn’t in the same class with General Sarnoff or Doctor Stanton.

Despite the uproar over inferior or inept television fare, McLuhan does not think that the program content of television has anything to do with the real changes TV has produced; no more than whether a book is trashy or a classic has anything to do with the process of reading it. The basic message of television is television itself, the process, just as the basic message of a book is print. As McLuhan says, “The medium is the message.”

This new view of our environment is much more realistic in the light of what has happened since the advent of McLuhan’s “Electric Age.” The Gutenberg Age, which preceded it, was one thing after another in orderly sequence from cause to effect. It reached its finest flower with the development of mechanical linkages: A acts on B which acts on C which acts on D on down to the end of the line and the finished product. The whole process was thus fragmented into a series of functions, and for each function there was a specialist. This methodology was not confined to making things; it pervaded our entire economic and social system. It still does, though we are in an age when cause and effect are becoming so nearly simultaneous as to make obsolete all our accustomed notions of chronological sequence and mechanical linkage. With the dawn of the Electric Age, time and speed themselves have become of negligible importance; just flip the switch. Instant speed.

However, our methodology and thought patterns are still, for the most part, based on the old fragmentation and specialism, which may account for some of our society’s confusion, or perhaps a great deal of it.•

“By 1975 Mao Tse-Tung Himself Would Be Bowing In Homage Before The Teenage Theomorphic Guru”

In 1973, Ken Kelley published a Ramparts profile of teenage guru Maharaji Ji, a.k.a. “The Perfect Master,” who had become popular at the time with Rennie Davis and some other gullible members of the American counterculture. It’s not the absolute best piece about the spiritual leader, but it’s good. The opening:

For an entire week, Berkeley buzzed in anticipation of the return of Rennie Davis. The incredible story of his conversion to the divine prodigy, Satguru Maharaj Ji, had been revealed in a 40-minute interview on the local FM rocker KSAN. Not only was he dedicating his entire life to Maharaj Ji, but by 1975 Mao Tse-tung himself would be bowing in homage before the teenage theomorphic guru. The reaction ranged from sympathy to Paul Krassner’s insistence that the entire enterprise was a CIA plot. In between were those who felt that Davis was bummed out by the abuse heaped on him as an active, white, male Movement heavy, disappointed by the disintegration of the anti-war movement and therefore open to the love-vibes and Telex technology which form the core of the Satguru’s appeal. Whatever the explanation, everyone was curious, and they itched to see the new Rennie Davis and hear him explain it all in the flesh.

He chose Pauley Ballroom on the U.C. campus to make his stand, a site which overlooks the famous Sproul Plaza. There, some eight years earlier, Mario Savio and his fellow students had marched to shut down the university, thereby unloosing a flood of campus protest which did not subside for five years. Rennie Davis had played a crucial role in that Movement. He had raised money, mapped strategy, given speeches, negotiated permits, written pamphlets-in short, he had done everything that the Movement had done and more. When others had grown tired and cynical, he had worked on and on, and it was only in recent months that he had begun to slacken his pace.

People had come to view Rennie Davis as better, more dedicated than the rest of us, and now, suddenly, he was telling us to surrender our hearts and minds to a barely pubescent self-proclaimed Perfect Master from India and waltz into Nirvana. It was as if Che Guevara had returned to recruit for the Campfire Girls: the anomaly was as profound as the amazement.

And so they packed the ballroom to hear Rennie Davis, and one sensed curiosity, a certain amount of hostility, and an undercurrent of fear. As he stood before the assemblage, the vultures descended. “Kiss my lotus ass.” “All power to the Maharajah, huh?” He took it in with smiles and good humor. “I’m really blissed out with a capital B,” he proclaimed in the vernacular of his new calling. “I’m just here to make a report, and if you don’t want to check out what I’m saying, that’s cool. Sooner or later you’ll find out that we are operating under a new leadership, and it is Divine, that it’s literally going to transform the planet into what we’ve always hoped and dreamed for.”•

“Ever Since Telephones Began To Make Money, There Have Been People Willing To Rob And Defraud Phone Companies”

A year after Ron Rosenbaum’s seminal 1971 Phone Phreak story in Esquire, Ramparts until now. In 1972, that publication ran step-by-step instructions of how someone could receive phone calls for free, sans blue box. In 1973, it published a piece by Bruce Sterling about the history of hacking which explained the pre-Phreak politicized past of phone rip-offs, which was a signature of the Yippie movement. An excerpt:

Abbie Hoffman is said to have caused the Federal Bureau of Investigation to amass the single largest investigation file ever opened on an individual American citizen. (If this is true, it is still questionable whether the FBI regarded Abbie Hoffman a serious public threat -quite possibly, his file was enormous simply because Hoffman left colorful legendry wherever he went). He was a gifted publicist, who regarded electronic media as both playground and weapon. He actively enjoyed manipulating network TV and other gullible, imagehungry media, with various weird lies, mindboggling rumors, impersonation scams, and other sinister distortions, all absolutely guaranteed to upset cops, Presidential candidates, and federal judges. Hoffman’s most famous work was a book self-reflexively known as Steal This Book, which publicized a number of methods by which young, penniless hippie agitators might live off the fat of a system supported by humorless drones. Steal This Book, whose title urged readers to damage the very means of distribution which had put it into their hands, might be described as a spiritual ancestor of a computer virus.

Hoffman, like many a later conspirator, made extensive use of pay- phones for his agitation work — in his case, generally through the use of cheap brass washers as coin-slugs.

During the Vietnam War, there was a federal surtax imposed on telephone service; Hoffman and his cohorts could, and did, argue that in systematically stealing phone service they were engaging in civil disobedience: virtuously denying tax funds to an illegal and immoral war. But this thin veil of decency was soon dropped entirely. Ripping-off the System found its own justification in deep alienation and a basic outlaw contempt for conventional bourgeois values. Ingenious, vaguely politicized varieties of rip-off, which might be described as ‘anarchy by convenience,’ became very popular in Yippie circles, and because rip-off was so useful, it was to survive the Yippie movement itself. In the early 1970s, it required fairly limited expertise and ingenuity to cheat payphones, to divert “free” electricity and gas service, or to rob vending machines and parking meters for handy pocket change. It also required a conspiracy to spread this knowledge, and the gall and nerve actually to commit petty theft, but the Yippies had these qualifications in plenty. In June 1971, Abbie Hoffman and a telephone enthusiast sarcastically known as ‘Al Bell’ began publishing a newsletter called Youth International Party Line. This newsletter was dedicated to collating and spreading Yippie rip-off techniques, especially of phones, to the joy of the freewheeling underground and the insensate rage of all straight people.

As a political tactic, phone-service theft ensured that Yippie advocates would always have ready access to the long-distance telephone as a medium, despite the Yippies’ chronic lack of organization, discipline, money, or even a steady home address.

Party Line was run out of Greenwich Village for a couple of years, then “Al Bell” more or less defected from the faltering ranks of Yippiedom, changing the newsletter’s name to TAP or Technical Assistance Program. After the Vietnam War ended, the steam began leaking rapidly out of American radical dissent. But by this time, ‘Bell’ and his dozen or so core contributors had the bit between their teeth, and had begun to derive tremendous gut-level satisfaction from the sensation of pure technical power.

TAP articles, once highly politicized, became pitilessly jargonized and technical, in homage or parody to the Bell System’s own technical documents, which TAP studied closely, gutted, and reproduced without permission. The TAP elite revelled in gloating possession of the specialized knowledge necessary to beat the system.

“Al Bell” dropped out of the game by the late 70s, and “Tom Edison” took over; TAP readers (some 1400 of them, all told) now began to show more interest in telex switches and the growing phenomenon of computer systems. In 1983, “Tom Edison” had his computer stolen and his house set on fire by an arsonist. This was an eventually mortal blow to TAP (though the legendary name was to be resurrected in 1990 by a young Kentuckian computeroutlaw named “Predat0r.”)

Ever since telephones began to make money, there have been people willing to rob and defraud phone companies. The legions of petty phone thieves vastly outnumber those “phone phreaks” who “explore the system” for the sake of the intellectual challenge. The New York metropolitan area (long in the vanguard of American crime) claims over 150,000 physical attacks on pay telephones every year! Studied carefully, a modern payphone reveals itself as a little fortress, carefully designed and redesigned over generations, to resist coinslugs, zaps of electricity, chunks of coin-shaped ice, prybars, magnets, lockpicks, blasting caps. Public pay- phones must survive in a world of unfriendly, greedy people, and a modern payphone is as exquisitely evolved as a cactus.•