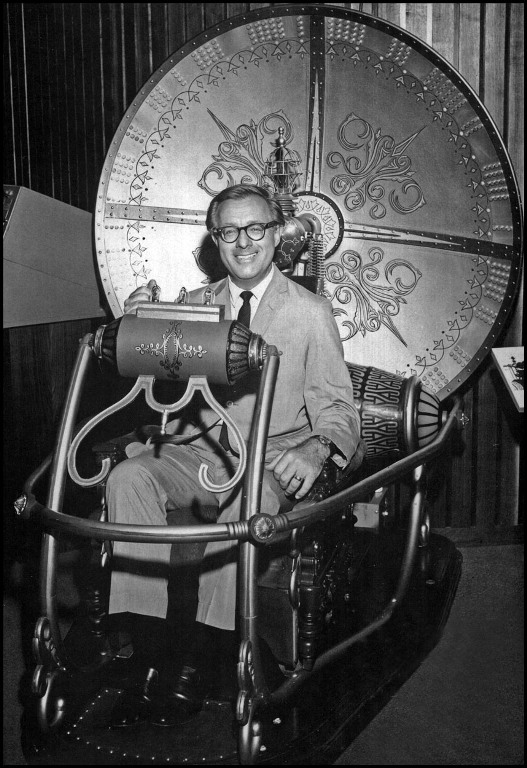

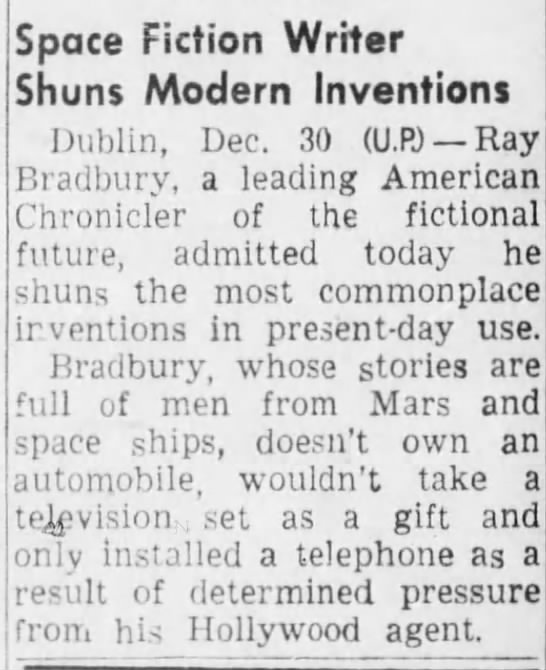

From the December 30, 1953 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

Tags: Ray Bradbury

Who has the next billion-dollar idea in Silicon Valley? If you’re like me, you don’t give a flying fuck.

But it is interesting that an industry so determined to inform our lives with algorithms, Big Data and Deep Learning basically throws shit at a wall and sees what will stick when it comes to doling out venture capital. Why wouldn’t VC investors use a more scientific Moneyball approach? I would guess it has something to do with ego.

From Claire Cain Miller at the New York Times:

Many people think they know what the founder of a tech start-up looks like: a 20-something man who spent his childhood playing on computers in his basement and who later dropped out of college to become a billionaire entrepreneur.

That describes Mark Zuckerberg, Steve Jobs and Bill Gates. But there’s just one thing: They are anomalies.

Most tech start-up founders who have successfully raised venture capital have much less unusual résumés, according to data analysis by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, Haas School of Business. The average founder is 38, with a master’s degree and 16 years of work experience.

Yet if someone like that came to a top venture capitalist’s office, he or she could very well be turned away. Start-up investors often accept pitches only from people they know, and rely heavily on gut feelings, intuition and what’s worked before. “I can be tricked by anyone who looks like Mark Zuckerberg,” Paul Graham, co-founder of the seed investor Y Combinator, once said.

That strategy, however, means that investors are likely to be missing some good bets.•

Tags: Claire Cain Miller, Paul Graham

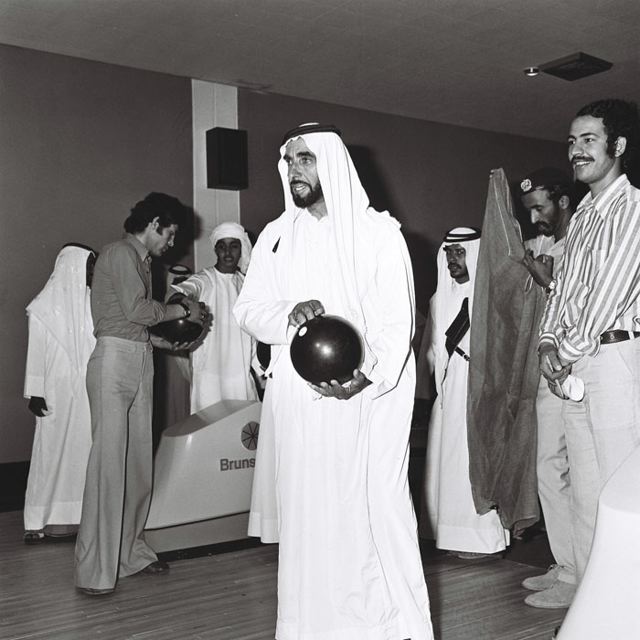

In the 1970s, AMF, the sporting-goods manufacturer, sold the DataMagic Bowling Data Computer, a system that would tabulate rankings of bowling leagues with the push of a button. It seems a stunning waste of computing power and coincided with the company going into a decline, so I doubt it was a big seller. But as this commercial makes clear, it was a declaration of war on the pencil.

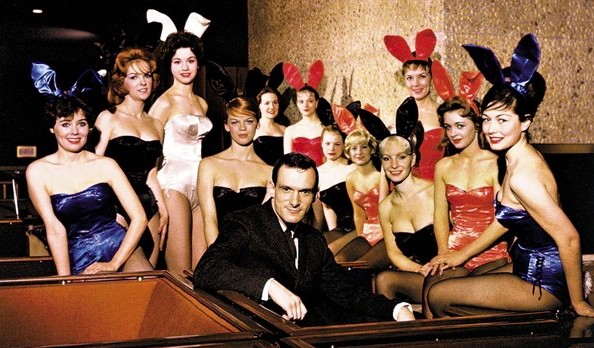

In 1966, when Playboy was still based in Chicago, Hugh Hefner thought most people would soon be enjoying his lifestyle. Well, not exactly his lifestyle.

The mansion, the grotto and the Bunnies were not likely for most, but he believed technology would help us remove ourselves from the larger world so that we could create our own “little planet.” The gadgets he used to extend his adolescence and recuse himself five decades ago are now much more powerful and affordable to almost everyone. Hefner believed our new, personalized islands would be our homes, not our phones, but he was right in thinking that tools would make life more remote in some fundamental way.

In 1966, Oriana Fallaci interviewed Hefner for her book, The Egotists. Her sharp introduction and the first exchange follow.

_________________________

First of all, the House. He stays in it as a Pharaoh in a grave, and so he doesn’t notice that the night has ended, the day has begun, a winter passed, and a spring, and a summer–it’s autumn now. Last time he emerged from the grave was last winter, they say, but he did not like what he saw and returned with great relief three days later. The sky was then extinguished behind the electronic gate, and he sat down again in his grave: 1349 North State Parkway, Chicago. But what a grave, boys! Ask those who live in the building next to it, with their windows opening onto the terrace on which the bunnies sunbathe, in monokinis or notkinis. (The monokini exists of panties only, the notkini consists of nothing.) Tom Wolfe has called the house the final rebellion against old Europe and its custom of wearing shoes and hats, its need of going to restaurants or swimming pools. Others have called it Disneyland for adults. Forty-eight rooms, thirty-six servants always at your call. Are you hungry? The kitchen offers any exotic food at any hour. Do you want to rest? Try the Gold Room, with a secret door you open by touching the petal of a flower, in which the naked girls are being photographed. Do you want to swim? The heated swimming pool is downstairs. Bathing suits of any size or color are here, but you can swim without, if you prefer. And if you go into the Underwater Bar, you will see the Bunnies swim as naked as little fishes. The House hosts thirty Bunnies, who may go everywhere, like members of the family. The pool also has a cascade. Going under the cascade, you arrive at the grotto, rather comfortable if you like to flirt; tropical plants, stereophonic music, drinks, erotic opportunities, and discreet people. Recently, a guest was imprisoned in the steam room. He screamed, but nobody came to help him. Finally, he was able to free himself by breaking down the door, and when he asked in anger, why nobody came to his help–hadn’t they heard his screams?–they answered, “Obviously. But we thought you were not alone.”

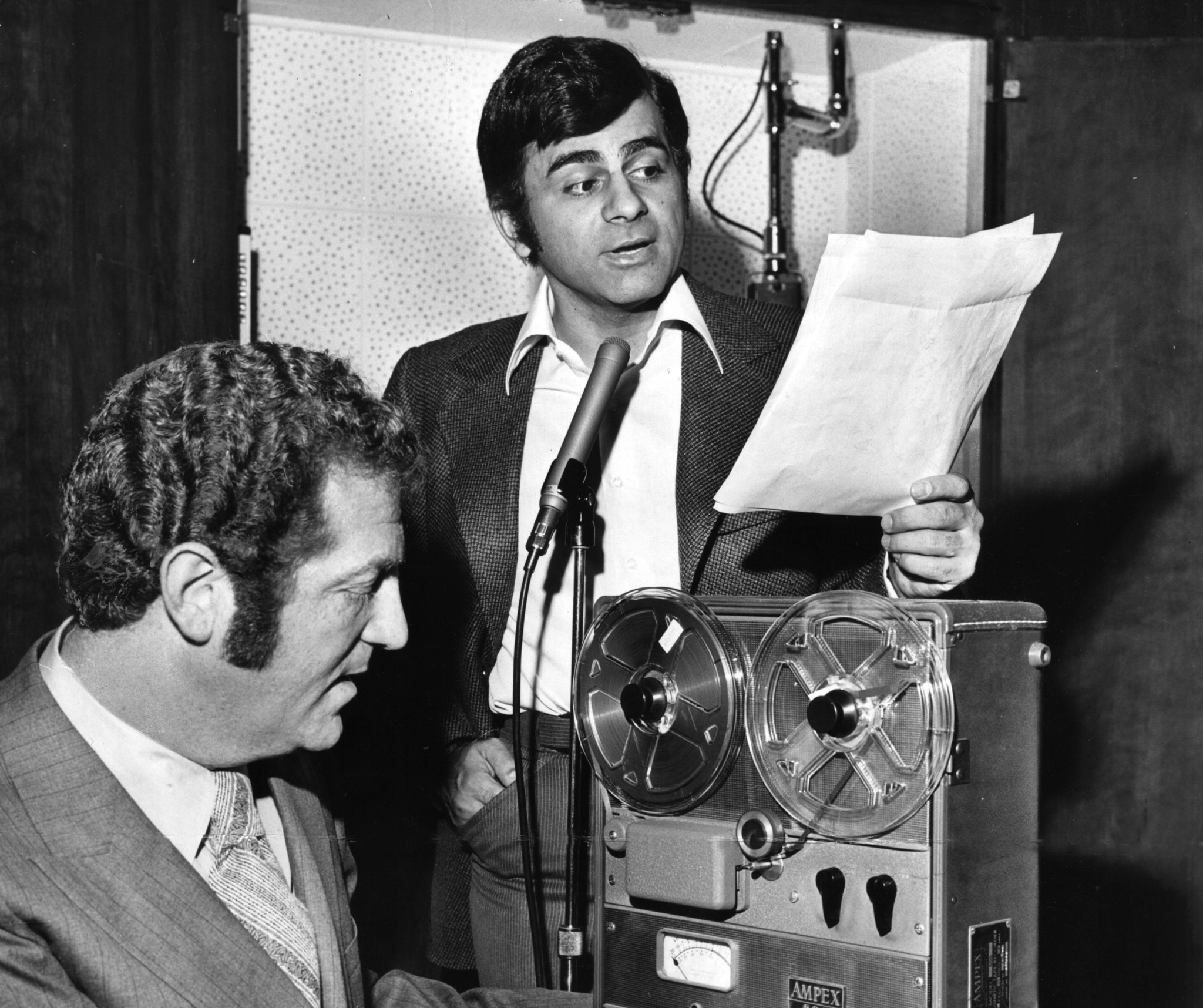

At the center of the grave, as at the center of a pyramid, is the monarch’s sarcophagus: his bed. It’s a large, round and here he sleeps, he thinks, he makes love, he controls the little cosmos that he has created, using all the wonders that are controlled by electronic technology. You press a button and the bed turns through half a circle, the room becomes many rooms, the statue near the fireplace becomes many statues. The statue portrays a woman, obviously. Naked, obviously. And on the wall there TV sets on which he can see the programs he missed while he slept or thought or made love. In the room next to the bedroom there is a laboratory with the Ampex video-tape machine that catches the sounds and images of all the channels; the technician who takes care of it was sent to the Ampex center in San Francisco. And then? Then there is another bedroom that is his office, because he does not feel at ease far from a bed. Here the bed is rectangular and covered with papers and photos and documentation on Prostitution, Heterosexuality, Sodomy. Other papers are on the floor, the chairs, the tables, along with tape recorders, typewriters, dictaphones. When he works, he always uses the electric light, never opening a window, never noticing the night has ended, the day begun. He wears pajamas only. In his pajamas, he works thirty-six hours, forty-eight hours nonstop, until he falls exhausted on the round bed, and the House whispers the news: He sleeps. Keep silent in the kitchen, in the swimming pool, in the lounge, everywhere: He sleeps.

He is Hugh Hefner, emperor of an empire of sex, absolute king of seven hundred Bunnies, founder and editor of Playboy: forty million dollars in 1966, bosoms, navels, behinds as mammy made them, seen from afar, close up, white, suntanned, large, small, mixed with exquisite cartoons, excellent articles, much humor, some culture, and, finally, his philosophy. This philosophy’s name is “Playboyism,” and, synthesized, it says that “we must not be afraid or ashamed of sex, sex is not necessarily limited to marriage, sex is oxygen, mental health. Enough of virginity, hypocrisy, censorship, restrictions. Pleasure is to be preferred to sorrow.” It is now discussed even by theologians. Without being ironic, a magazine published a story entitled “…The Gospel According to Hugh Hefner.” Without causing a scandal, a teacher at the School of Theology at Claremont, California, writes that Playboyism is, in some ways, a religious movement: “That which the church has been too timid to try, Hugh Hefner…is attempting.”

We Europeans laugh. We learned to discuss sex some thousands of years ago, before even the Indians landed in America. The mammoths and the dinosaurs still pastured around New York, San Francisco, Chicago, when we built on sex the idea of beauty, the understanding of tragedy, that is our culture. We were born among the naked statues. And we never covered the source of life with panties. At the most, we put on it a few mischievous fig leaves. We learned in high school about a certain Epicurus, a certain Petronius, a certain Ovid. We studied at the university about a certain Aretino. What Hugh Hefner says does not make us hot or cold. And now we have Sweden. We are all going to become Swedish, and we do not understand these Americans, who, like adolescents, all of a sudden, have discovered that sex is good not only for procreating. But then why are half a million of the four million copies of the monthly Playboy sold in Europe? In Italy, Playboy can be received through the mail if the mail is not censored. And we must also consider all the good Italian husbands who drive to the Swiss border just to buy Playboy. And why are the Playboy Clubs so famous in Europe, why are the Bunnies so internationally desired? The first question you hear when you get back is: “Tell me, did you see the Bunnies? How are they? Do they…I mean…do they?!?” And the most severe satirical magazine in the U.S.S.R., Krokodil, shows much indulgence toward Hugh Hefner: “[His] imagination in indeed inexhaustible…The old problem of sex is treated freshly and originally…”

Then let us listen with amusement to this sex lawmaker of the Space Age. He’s now in his early forties. Just short of six feet, he weighs one hundred and fifty pounds. He eats once a day. He gets his nourishment essentially from soft drinks. He does not drink coffee. He is not married. He was briefly, and he has a daughter and a son, both teen-agers. He also has a father, a mother, a brother. He is a tender relative, a nepotist: his father works for him, his brother, too. Both are serious people, I am informed.

And then I am informed that the Pharaoh has awakened, the Pharaoh is getting dressed, is going to arrive, has arrived: Hallelujah! Where is he? He is there: that young man, so slim, so pale, so consumed by the lack of light and the excess of love, with eyes so bright, so smart, so vaguely demoniac. In his right hand he holds a pipe: in his left hand he holds a girl, Mary, the special one. After him comes his brother, who resembles Hefner. He also holds a girl, who resembles Mary. I do not know if the pipe he owns resembles Hugh’s pipe because he is not holding one right now. It’s a Sunday afternoon, and, as on every Sunday afternoon, there is a movie in the grave. The Pharaoh lies down on the sofa with Mary, the light goes down, the movie starts. The Bunnies go to sleep and the four lovers kiss absentminded kisses. God knows what Hugh Hefner thinks about men, women, love, morals–will he be sincere in his nonconformity? What fun, boys, if I discover that he is a good, proper moral father of Family whose destiny is paradise. Keep silent, Bunnies. He speaks. The movie is over, and he speaks, with a soft voice that breaks. And, I am sure, without lying.

Oriana Fallaci:

A year without leaving the House, without seeing the sun, the snow, the rain, the trees, the sea, without breathing the air, do you not go crazy? Don’t you die with unhappiness?

Hugh Hefner:

Here I have all the air I need. I never liked to travel: the landscape never stimulated me. I am more interested in people and ideas. I find more ideas here than outside. I’m happy, totally happy. I go to bed when I like. I get up when I like: in the afternoon, at dawn, in the middle of the night. I am in the center of the world, and I don’t need to go out looking for the world. The rational use that I make of progress and technology brings me the world at home. What distinguishes men from other animals? Is it not perhaps their capacity to control the environment and to change it according to their necessities and tastes? Many people will soon live as I do. Soon, the house will be a little planet that does not prohibit but helps our relationships with the others. Is it not more logical to live as I do instead of going out of a little house to enter another little house, the car, then into another little house, the office, then another little house, the restaurant or the theater? Living as I do, I enjoy at the same time company and solitude, isolation from society and immediate access to society. Naturally, in order to afford such luxury, one must have money. But I have it. And it’s delightful.•

Tags: Hugh Hefner, Oriana Fallaci

How do we reconcile largely free-market economies with highly automated ones? That depends.

If a scary number of jobs disappear into the algorithms and are readily replaced by new positions in industries we’ve yet to imagine, then it’s a bumpy changeover but not a massive upheaval. But why wouldn’t those jobs also be roboticized? Really, only trucking, delivery and construction have to lose their human workers for serious remedies to be required. Universal basic income is often cited as one potential solution.

From Josefin Smeds at Smarter Together:

For a long time, an argument in favor of automatization has been that it frees up time for people to work less and spend more time on family, leisure, and hobbies. Unfortunately, reality has shown that this has not been the result. Rather, some of us work a lot more than before whereas others are struggling to even break into the job market.

What are the alternatives then? Here is a little optimism along with some thought-provoking ideas. Jobs disappearing and tasks being carried out by machines do not have to be an entirely bad thing. Basic income is an intriguing (and somewhat controversial) concept where each citizen gets a regular “citizen salary” from the government, enough to cover expenses for basic needs. Supposedly, this would enable people to do what they really want to do in life, rather than working just to get bread on the table. The money for this basic income could, at least partly, be taken from the savings made from reduced government expenses on unemployment allowances and social security.•

Tags: Josefin Smeds

You hear an awful lot about how America is falling behind in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) education, that there’s a shortfall of graduates in those areas for now and the future. But labor statistics don’t back this claim.

Silicon Valley has been particularly loud about wanting foreign applicants fast-tracked for visas and citizenship. The situation is dire, they insist. Perhaps whether we’re talking about apple pickers or Apple engineers, this protest is more about want than need.

From Andrew Hacker’s NYRB piece “The Frenzy About High-Tech Talent“:

A variety of American industries have long held that their survival depends on being permitted to bring in foreign workers. Most familiar has been much of agriculture, which claims that resident citizens will not take the pay that employers can afford. Today the technology sector is making a similar plea, with the obvious difference that it needs more cerebral skills. Under H-1B, candidates must be sponsored by specified employers, with elaborate paperwork on both sides, including avowals that the domestic workforce has been thoroughly combed for qualified candidates. Apparently, the time spent on such applications is worth it.

As of the end of 2012, fully 262,569 H-1B visa-holders were working in the United States. By far the most were from India (168,367), with China a distant second (19,850). Indians are most wanted because they come knowing English and can start on assignments the day after they arrive. Topping the list are “computer-related occupations,” such as coding, followed by engineering. Microsoft leads the employers’ list, with Intel, IBM, and Oracle close behind. But a host of enterprises now have software systems in need of servicing. The H-1B roster also includes Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan Chase, and the Rite-Aid pharmacy chain.

A central question, of course, is why Americans weren’t available or applying for these 262,569 jobs. During the 2001–2011 decade, the most recent for which we have figures, our colleges turned out some 2.5 million graduates in computer science and engineering, which seems a fair-sized pool. On its face, it should contain enough people with the qualifications that Microsoft and Oracle and Rite-Aid expect. One explanation is that these and other firms in fact prefer people from abroad. Indeed, many are already in universities here, where they receive half the graduate degrees in computer science and engineering. Of students from India awarded Ph.D.s, 85 percent were still in the US five years after receiving their degrees.

James Bach and Robert Werner’s How to Secure Your H-1B Visa is written for both employers and the workers they hire. They are told that firms must “promise to pay any H-1B employee a competitive salary,” which in theory means what’s being offered “to others with similar experience and qualifications.” At least, this is what the law says. But then there are figures compiled by Zoe Lofgren, who represents much of Silicon Valley in Congress, showing that H-1B workers average 57 percent of the salaries paid to Americans with comparable credentials.

Norman Matloff, a computer scientist at the University of California’s Davis campus, provides some answers. The foreigners granted visas, he found, are typically single or unattached men, usually in their late twenties, who contract for six-year stints, knowing they will work long hours and live in cramped spaces. Being tied to their sponsoring firm, Matloff adds, they “dare not switch to another employer” and are thus “essentially immobile.” For their part, Bach and Warner warn, “it may be risky for you to give notice to your current employer.” Indeed, the perils include deportation if you can’t quickly find another guarantor.

Matloff also found that employers “tailor job requirements so that only the desired foreign applicants qualify” and they “have an arsenal of legal means to reject all US workers who apply.”•

Tags: Andrew Hacker

I own almost nothing. Seriously. My laptop and phone and whatever books I’m reading right now and some clothes. That’s it. But some collect and others hoard, and the latter’s driven by a deep psychological impulse. I suspect it has something to do with a desire for permanence, a vain attempt to defeat death.

Of course, the Borrowing Economy has made it possible to unclutter our lives somewhat, as information, rather than a physical product, is traded, the hardware disappeared into the software. In “Why You Soon Won’t Own Anything And Why That’s A Good Thing,” Johannes Koponen of Demos Helsinki believes this trend will not just continue apace but reach maximum speed. An excerpt:

Things get really interesting when we start talking about cars instead of music. What would it be like to access a car on-demand? You might say that we already have taxis. But a taxi isn’t as convenient as Netflix is. What would it be like to actually have the convenience of your own car without owning it?

Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) is a model for traffic without ownership. You pay a monthly fee for it, like with Spotify, tell the app where you are going and get instnat access to taxis, Ubers, buses, and so on. Everything is available on-demand and ownership is no longer needed.

MaaS is part of a trend called the “as a service” model. The framework began as a simple idea in software development, when companies started paying for access instead of buying permanent licenses for office programs. Now the same model is moving into the material world. Netflix, Spotify, AirBnb and Uber are all “as a service” companies.

“As a service” models become more and more feasible when the number of sensors that surround us increases. This development is often called the “Internet of Things”. But when we consider the Internet of Things from the perspective of disappearing products and the increase in new service models, we can effectively conclude that it is, in fact, the “Internet of No Things.”

What is so revolutionary about the “as a service” model then? Why is it good not to own things? There are two main reasons and these are related:

- Ownership makes us lazy.

- The planet cannot survive with us consuming so much stuff.•

Tags: Johannes Koponen

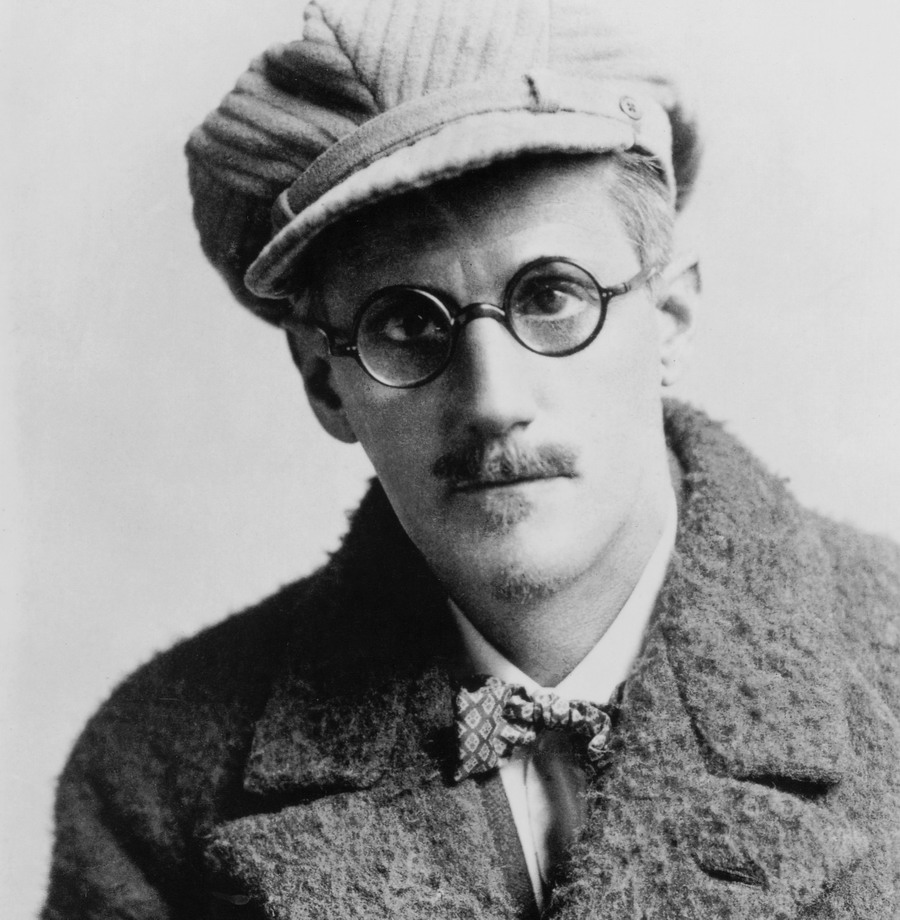

Some tell the truth–or their version of it–through exaggeration, assigning perceived offenses Brobdingnagian proportions. Dale Peck, erstwhile enfant terrible, has a permanent place in that canon. In Christopher Frizzelle’s well-written Stranger piece, “Literature’s Biggest Asshole Shows His Soft Side,” the literary terror’s new memoir about living through the age of AIDS is compared pretty much favorably to Didion. The opening:

Dale Peck is one of those writers who’s infamous among literary types and unheard of among normal people. His book reviews 10 years ago were all anyone could talk about. They were mean and unpredictable. He called Rick Moody “the worst writer of his generation” in the New Republic, the same magazine in which he compared Ulysses to diarrhea. He was a grandstander and a flamethrower, which made him fun to read, but it was fun in the sense that a demolition derby is “fun.” You experienced the fun while distrusting anyone who would go to such lengths to make it fun. The suspense in Hatchet Jobs, Peck’s book of collected takedowns, was in watching him bring every weapon he’s ever owned to the task of “proving” good writers were bad writers. He seemed to have endless energy for that project.

Those essays bothered people, but they didn’t bother me. (Especially because the very last essay in the book does nothing but praise Rebecca Brown.) Anyone who’s read vicious reviews by Dorothy Parker, Virginia Woolf, Mary McCarthy, Pauline Kael, or Joan Didion would be able to see that Peck’s pieces are part of a long tradition: non-hetero-white-men ripping apart hetero-white-male work. Peck’s essays were more reckless and shameless than, say, McCarthy’s piece on J.D. Salinger, but just as elegant. Literary folks were scandalized and aghast, but literary folks love to be scandalized and aghast. (Can you believe someone wouldexaggerate in print? My word.)

In April, Dale Peck published a book that doesn’t consist of Dale Peck going around telling everyone what their problem is. Visions and Revisions is about being gay and living through the “hothouse” period of AIDS, from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. It’s full of previously published chunks of journalism and memoir that have been submerged in molten time, and then hardened and cooled into Literature. It’s funny and full of sex, in addition to being sad and full of ghosts.

AIDS is the perfect subject for a born exaggerator like Peck.•

Tags: Christopher Frizzelle, Dale Peck

Mollie Fancher didn’t exactly sleep through history, but she certainly reclined as it passed by.

The odd woman, known as the “Brooklyn Enigma,” reportedly suffered a pair of accidents in the 1860s while on the cusp of adulthood and repaired to her bedroom where she spent the rest of her life, saying that she could no longer walk. It’s not something you’d normally question, but doctors could never precisely figure out her condition, and Fancher became known for her strange claims that she could go years without solid food (a “fasting girl,” she was called) and that she was a clairvoyant. (It’s also possible she had multiple personalities.) Over the next 50 years (or 438,000 hours), some of which she shared with her parrot, Joe, the Brooklyn Bridge was built, streetcars and automobiles began replacing horses and the telephone was patented and proliferated. All the while, Fancher clung to her pillow.

One month before her death, she celebrated five decades of being bedridden with a party of sorts, as was recorded in an article the January 30, 1916 Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

Tags: Mollie Fancher

In the year 2100, how much of construction will remain in human hands? Precious little, I would think.

Pluses include much cheaper structures that are much quicker to completion, home costs being lower and personalized architecture being readily available. The chief minus is, of course, the number of jobs lost. If just the construction and trucking industries were lost to printing and automation, that would leave a huge gulf in the U.S. Labor market.

From Andrew Torchia of Reuters:

DUBAI (Reuters) – Dubai said it would construct a small office building using a 3D printer for the first time, in a drive to develop technology that would cut costs and save time as the city grows.

3D printing, which uses a printer to make three-dimensional objects from a digital design, is taking off in manufacturing industries around the world but has so far been used little in construction.

Dubai’s one-storey prototype building, with about 2,000 square feet (185 square meters) of floor space, will be printed layer-by-layer using a 20-foot tall printer, Mohamed Al Gergawi, the United Arab Emirates Minister of Cabinet Affairs, said on Tuesday.

It would then be assembled on site within a few weeks. Interior furniture and structural components would also be built through 3D printing with reinforced concrete, gypsum reinforced with glass fiber, and plastic.•

Tags: Andrew Torchia

I’ve read some titles from the Financial Times “Summer Books 2015” list, including Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens, Evan Osnos’ Age of Ambition and Martin Ford’s Rise of the Robots, all of which are wonderful–in fact, Harari’s title is the best book I’ve read this year, period. Here are several more suggestions from FT which sound great:

Station Eleven (Emily St. John Mandel) is an apocalyptic novel about a world in which almost everyone has died in a flu pandemic, and clans roam the earth killing at random. It could hardly sound less promising. And yet Emily St John Mandel’s fourth novel is different partly because she skips over the apocalypse itself — all the action takes place just before or 20 years afterwards — and because it is less about the survival of the human race than the survival of Shakespeare. The book has been on literary shortlists and won prizes and been much praised for its big themes: culture, memory, loss. Yet it works just as well at a less lofty level, as a beautifully written, compulsive read.

A Kim Jong-Il Production (Paul Fischer) The story of how the late North Korean dictator kidnapped South Korean cinema’s golden couple, the director Shin Sang-ok and his actress wife Choi Eun-hee, and put them to work building a film industry in the North. At once a gripping personal narrative and an insight into the cruelty and madness of North Korea.

The Vital Question: Why is Life the Way It Is? (Nick Lane) Biochemist Lane offers a scintillating synthesis of a new theory of life, emphasising the interplay between energy and evolution. He shows how simple microbes, which monopolised Earth for the first 2bn years, took the momentous step towards becoming the “eukaryotic” cells that then evolved into animals, plants, fungi and protozoa.•

Tags: Emily St. John Mandel, Evan Osnos, Kim Jong-il, Martin Ford, Nick Lane, Paul Fischer, Yuval Noah Harari

The biggest problem with the Huffington Post isn’t the incessant lewd and lurid clickbait used to lure eyeballs, but that the money derived from such garbage is used to support very, very little good journalism. The site has been touted as navigating the way forward for the news business, but it isn’t that. The company might as well be selling Ding Dongs or Whoppers. It’s a gigantic operation coming to very little good and some bad (e.g., its early support of the anti-vaccination movement helped propel that lunacy). Ultimately, the site is its own strange island having no ramifications beyond its borders for anyone who wants to do responsible journalism. It’s not a news business, really, just a business and a dubious one.

Early on in “Arianna Huffington’s Improbable, Insatiable Content Machine,” David Segal’s knowing New York Times Magazine article, the founder says this about a new vertical: “Let’s start iterating…let’s not wait for the perfect product.’’ And that’s true of the site writ large: It’s just iteration, and there’s no reason to anticipate it becoming perfect or even just good. That wait is over.

From Segal:

When most sites were merely guessing about what would resonate with readers, The Huffington Post brought a radical data-driven methodology to its home page, automatically moving popular stories to more prominent spaces and A-B testing its headlines. The site’s editorial director, Danny Shea, demonstrated to me how this works a few months ago, opening an online dashboard and pulling up an article about General Motors. One headline was ‘‘How GM Silenced a Whistleblower.’’ Another read ‘‘How GM Bullied a Whistleblower.’’ The site had automatically shown different headlines to different readers and found that ‘‘Silence’’ was outperforming ‘‘Bully.’’ So ‘‘Silence’’ it would be. It’s this sort of obsessive data analysis that has helped web-headline writing become so viscerally effective.

Above all, from its founding in an era dominated by ‘‘web magazines’’ like Slate, The Huffington Post has demonstrated the value of quantity. Early in its history, the site increased its breadth on the cheap by hiring young writers to quickly summarize stories that had been reported by other publications, marking the birth of industrial aggregation.

Today, The Huffington Post employs an armada of young editors, writers and video producers: 850 in all, many toiling at an exhausting pace. It publishes 13 editions across the globe, including sites in India, Germany and Brazil. Its properties collectively push out about 1,900 posts per day. In 2013, Digiday estimated that BuzzFeed, by contrast, was putting out 373 posts per day, The Times 350 per day and Slate 60 per day. (At the time, The Huffington Post was publishing 1,200 posts per day.) Four more editions are in the works — The Huffington Post China among them — and a franchising model will soon take the brand to small and midsize markets, according to an internal memo Huffington sent in late May.Throughout its history, the site’s scale has also depended on free labor. One of Huffington’s most important insights early on was that if you provide bloggers with a big enough stage, you don’t have to pay them.•

Tags: Arianna Huffington, David Segal

I certainly don’t know enough about Utrecht’s economy to say if the Dutch city’s plan to provide universal basic income is a good one or what the success or failure of the experiment would mean, if anything, beyond its borders, but it certainly will get rid of a lot of bureaucracy. In the U.S., the measuring of the needs of people across a multitude of plans carries heavy administrative costs.

From DutcheNews.nl:

Utrecht city council is to begin experimenting with the idea of a basic income, replacing the current complicated system of taxes, social security benefits and top-up benefits.

City alderman Victor Everhardt says the aim is to see if the concept of a basic income works in practice. ‘Things can be simpler if we base the system on trust,’ he told website DeStadUtrecht.nl.

The experiment will start after the summer holidays and is being carried out together with researchers from Utrecht University.

In theory, a basic income consists of a flat income to cover living costs which, supporters say, will free up people to work more flexible hours, do volunteer work and study. Additional income is subject to income tax.

The Utrecht project will focus on people claiming welfare benefits. One group will continue under the present system of welfare plus supplementary benefits for housing and health insurance. A second group will get benefits based on a system of incentives and rewards and a third group will have a basic income with no extras.•

Tags: Victor Everhardt

Not everything should be left to the algorithms, but the drawing of U.S. congressional districts is one that cries out for such a technological shift. When members of congress, who collectively have a seven-percent approval rating, don’t have to worry about the security of their day jobs, gerrymandering has reached a ridiculous level. And if you can’t throw the bums out, you become Bumtown.

A half-step in the right direction is the Supreme Court decision which supports independent redistricting. It will still be people, prone to prejudices, doing the job, but at least it doesn’t allow for an outright “land grab.”

From Adam Liptak at the New York Times:

The case, Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, No. 13-1314, concerned an independent commission created by Arizona voters in 2000. About a dozen states have experimented with redistricting commissions that have varying degrees of independence from the state legislatures, which ordinarily draw election maps. Arizona’s commission is most similar to California’s.

The Arizona commission has five members, with two chosen by Republican lawmakers and two by Democratic lawmakers. The final member is chosen by the four others.

The Republican-led State Legislature sued, saying the voters did not have the authority to strip elected lawmakers of their power to draw district lines. They pointed to the elections clause of the federal Constitution, which says, “The times, places and manner of holding elections for senators and representatives shall be prescribed in each state by the legislature thereof.”

Justice Ginsburg wrote that the Constitution’s reference to “legislature” encompassed the people’s legislative power when acting through ballot initiatives. “The animating principle of our Constitution is that the people themselves are the originating source of all the powers of government,” she wrote.•

Tags: Adam Liptak, Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Volunteer for joke writer for feature film

Please send some jokes if you’d like to volunteer.

Movie Plot:

A poet turns to selling medical marijuana to make money. Along his journey he tries to help 5 strangers everyday by helping anyway he can. The poet’s best friend is arrested and held for blackmail by a DEA captain, and the poet does his best to pay off the DEA captain and help others along the way. He meets a beautiful nurse along the way.

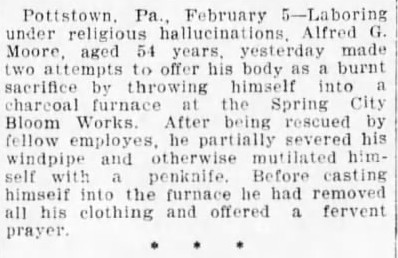

Tags: Alfred G. Moore

Ant colonies are analogous in many ways with human societies and computer systems, operating as a cooperative with the help of innate algorithms. In a Quanta Magazine Q&A, Emily Singer speaks to Stanford biologist Deborah Gordon about how these tiny builders can help us learn how to better assimilate the Information Age’s flood of data. An excerpt:

Question:

How do ant colonies change over time?

Deborah Gordon:

I found that a harvester ant colony’s behavior changes as it gets older and larger. Some aspects of network behavior just depend on size. In harvester ants, individual worker ants (other than the queen) live only a year, so it’s not the ants that get older and wiser, it’s the colony. That’s a puzzle, and it got me thinking about interaction networks, because I was looking for something that the ants could do in the same way but would have a different outcome if there are more ants. For example, I’m an ant, and I follow a rule that says, if I meet another ant at a certain rate, I do x. In a large colony, I might meet more ants. The same rule might have a different outcome if the colony is bigger because the rate of interaction would change.

We’re surrounded by giant networks — the Internet, our brains — so that got me interested in other systems. How does the behavior of a network scale as it gets larger?

Question:

How does it scale?

Deborah Gordon:

Older ant colonies are much more stable than young ones. If you create a disturbance, such as making a mess for them to clean up — I put out little piles of toothpicks — the older colonies eventually ignore the mess and get back to foraging. I think that in these colonies, with large numbers of foragers, the processes that drive them to forage override the response to the mess.•

Tags: Deborah Gordon, Emily Singer

Did life on Earth have to turn out this way? Oh, I’d like to think it was all an accident.

In “Last Hominin Standing,” a bright and eloquent Aeon piece, Dan Falk weighs whether the semi-intelligent life we call Homo sapiens simply had to be or if we’re the result of a series of lucky bounces in distant history. Did we depend entirely on a certain spiny eel-esque creature surviving extinction? Without a course-altering asteroid making an impression, would it still be a planet of dinosaurs? The late paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould believed our existence a contingent one, though he had no shortage of willing debaters on the topic. My particular favorite part of Falk’s essay is the passage on a theoretical world, free of Homo sapiens, that became dominated by Neanderthals. An excerpt:

If we re-played the tape of evolution, so to speak, would Homo sapiens – or something like it – arise once again, or was humanity’s emergence contingent on a highly improbable set of circumstances?

At first glance, everything that’s happened during the 3.8 billion-year history of life on our planet seems to have depended quite critically on all that came before. And Homo sapiens arrived on the scene only 200,000 years ago. The world got along just fine without us for billions of years. Gould didn’t mention chaos theory in his book, but he described it perfectly: ‘Little quirks at the outset, occurring for no particular reason, unleash cascades of consequences that make a particular future seem inevitable in retrospect,’ he wrote. ‘But the slightest early nudge contacts a different groove, and history veers into another plausible channel, diverging continually from its original pathway.’

One of the first lucky breaks in our story occurred at the dawn of biological complexity, when unicellular life evolved into multicellular. Single-cell organisms appeared relatively early in Earth’s history, around a billion years after the planet itself formed, but multicellular life is a much more recent development, requiring a further 2.5 billion years. Perhaps this step was inevitable, especially if biological complexity increases over time – but does it? Evolution, we’re told, does not have a ‘direction’, and biologists balk at any mention of ‘progress’. (The most despised image of all is the ubiquitous monkey-to-man diagram found in older textbooks – and in newer ones too, if only because the authors feel the need to denounce it.) And yet, when we look at the fossil record, we do, in fact, see, on average, a gradual increase in complexity.

But a closer look takes out some of the mystery of this progression. As Gould pointed out, life had to begin simply – which means that ‘up’ was the only direction for it to go. And indeed, a recent experiment suggests that the transition from unicellular to multicellular life was, perhaps, less of a hurdle than previously imagined. In a lab at the University of Minnesota, the evolutionary microbiologist William Ratcliff and his colleagues watched a single-celled yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) evolve into many-cell clusters in fewer than 60 days. The clusters even displayed some complex behaviours – including a kind of division of labour, with some cells dying so that others could grow and reproduce.

But even if evolution has a direction, happenstance can still intervene.•

Tags: Dan Falk

While futzing around on Reddit, I came across a link to “Darwin Among the Machines,” a piece from Samuel Butler’s A First Year in Canterbury Settlement, which, amazingly, was written in 1863, when he was beginning to put together Erewhon. An excerpt:

The views of machinery which we are thus feebly indicating will suggest the solution of one of the greatest and most mysterious questions of the day. We refer to the question: What sort of creature man’s next successor in the supremacy of the earth is likely to be. We have often heard this debated; but it appears to us that we are ourselves creating our own successors; we are daily adding to the beauty and delicacy of their physical organisation; we are daily giving them greater power and supplying by all sorts of ingenious contrivances that self-regulating, self-acting power which will be to them what intellect has been to the human race. In the course of ages we shall find ourselves the inferior race. Inferior in power, inferior in that moral quality of self-control, we shall look up to them as the acme of all that the best and wisest man can ever dare to aim at. No evil passions, no jealousy, no avarice, no impure desires will disturb the serene might of those glorious creatures. Sin, shame, and sorrow will have no place among them. Their minds will be in a state of perpetual calm, the contentment of a spirit that knows no wants, is disturbed by no regrets. Ambition will never torture them. Ingratitude will never cause them the uneasiness of a moment. The guilty conscience, the hope deferred, the pains of exile, the insolence of office, and the spurns that patient merit of the unworthy takes—these will be entirely unknown to them. If they want “feeding” (by the use of which very word we betray our recognition of them as living organism) they will be attended by patient slaves whose business and interest it will be to see that they shall want for nothing. If they are out of order they will be promptly attended to by physicians who are thoroughly acquainted with their constitutions; if they die, for even these glorious animals will not be exempt from that necessary and universal consummation, they will immediately enter into a new phase of existence, for what machine dies entirely in every part at one and the same instant?

We take it that when the state of things shall have arrived which we have been above attempting to describe, man will have become to the machine what the horse and the dog are to man. He will continue to exist, nay even to improve, and will be probably better off in his state of domestication under the beneficent rule of the machines than he is in his present wild state. We treat our horses, dogs, cattle, and sheep, on the whole, with great kindness; we give them whatever experience teaches us to be best for them, and there can be no doubt that our use of meat has added to the happiness of the lower animals far more than it has detracted from it; in like manner it is reasonable to suppose that the machines will treat us kindly, for their existence is as dependent upon ours as ours is upon the lower animals. They cannot kill us and eat us as we do sheep; they will not only require our services in the parturition of their young (which branch of their economy will remain always in our hands), but also in feeding them, in setting them right when they are sick, and burying their dead or working up their corpses into new machines. It is obvious that if all the animals in Great Britain save man alone were to die, and if at the same time all intercourse with foreign countries were by some sudden catastrophe to be rendered perfectly impossible, it is obvious that under such circumstances the loss of human life would be something fearful to contemplate—in like manner were mankind to cease, the machines would be as badly off or even worse. The fact is that our interests are inseparable from theirs, and theirs from ours. Each race is dependent upon the other for innumerable benefits, and, until the reproductive organs of the machines have been developed in a manner which we are hardly yet able to conceive, they are entirely dependent upon man for even the continuance of their species. It is true that these organs may be ultimately developed, inasmuch as man’s interest lies in that direction; there is nothing which our infatuated race would desire more than to see a fertile union between two steam engines; it is true that machinery is even at this present time employed in begetting machinery, in becoming the parent of machines often after its own kind, but the days of flirtation, courtship, and matrimony appear to be very remote, and indeed can hardly be realised by our feeble and imperfect imagination.

Day by day, however, the machines are gaining ground upon us; day by day we are becoming more subservient to them; more men are daily bound down as slaves to tend them, more men are daily devoting the energies of their whole lives to the development of mechanical life. The upshot is simply a question of time, but that the time will come when the machines will hold the real supremacy over the world and its inhabitants is what no person of a truly philosophic mind can for a moment question.•

Tags: Samuel Butler

Somebody able to read psychology and situations at will can do amazing things, but there aren’t enough such people to go around. Many of those leading governments, corporations, HR departments, etc., are clueless as fuck, and that has an unfortunate ripple effect on others.

Enter data analysis. Can it consistently–or at least more consistently than us–get the answer right, identifying market inefficiencies and inequalities? In many cases, it couldn’t do much worse, especially when you factor in the unwitting biases within us. In “The Data or the Hunch,” Ian Leslie’s Economist Intelligent Life article, the writer uses the story of legendary record-industry figure John Hammond, who made informed bets on Billie and Basie and Bob without the aid of algorithms, to analyze Moneyball and human error. Could a computer have heard in Dylan’s voice what Hammond did? Will AI be better on average but be prone to missing the black swan? An excerpt:

The old music industry turned many young acts into big stars. But it placed many, many more wagers on acts that didn’t sell enough records to pay back; William Goldman’s axiom, “Nobody knows anything,” applies to music as much as the movies. In the social-media era, big bets on untested talent are rarer. This is partly because there’s less money to spray around. But also because the record companies are using data to lower the risk.

This is the day of the analyst. In education, academics are working their way towards a reliable method of evaluating teachers, by running data on test scores of pupils, controlled for factors such as prior achievement and raw ability. The methodology is imperfect, but research suggests that it’s not as bad as just watching someone teach. A 2011 study led by Michael Strong at the University of California identified a group of teachers who had raised student achievement and a group who had not. They showed videos of the teachers’ lessons to observers and asked them to guess which were in which group. The judges tended to agree on who was effective and ineffective, but, 60% of the time, they were wrong. They would have been better off flipping a coin. This applies even to experts: the Gates Foundation funded a vast study of lesson observations, and found that the judgments of trained inspectors were highly inconsistent.

THE LAST STRONGHOLD of the hunch is the interview. Most employers and some universities use interviews when deciding whom to hire or admit. In a conventional, unstructured interview, the candidate spends half an hour or so in a conversation directed at the whim of the interviewer. If you’re the one deciding, this is a reassuring practice: you feel as if you get a richer impression of the person than from the bare facts on their résumé, and that this enables you to make a better decision. The first theory may be true; the second is not.

Decades of scientific evidence suggest that the interview is close to useless as a tool for predicting how someone will do a job. Study after study has found that organisations make better decisions when they go by objective data, like the candidate’s qualifications, track record and performance in tests. “The assumption is, ‘if I meet them, I’ll know’,” says Jason Dana, of Yale School of Management, one of many scholars who have looked into the interview’s effectiveness. “People are wildly over-confident in their ability to do this, from a short meeting.” When employers adopt a holistic approach, combining the data with hunches formed in interviews, they make worse decisions than they do going on facts alone.

The interview isn’t just unreliable, it is unjust, because it offers a back door for prejudice.•

Tags: Ian Leslie, John Hammond

I guess the biggest difference between the Web 1.0 bubble and the one we may be experiencing now is that no one this time thinks the Internet will suffer long-term damage even if stocks should founder badly. That actually was a fear among some during the first stunning downturn, that it had all been a flash in the pan, that we’d mistaken a frenzy for a fundamental shift. It was silly, of course, even if the jolt to the big-picture economy was painful. As had been the case with earlier, non-virtual gold rushes which left new cities in their wake, the infrastructure built in support of the burgeoning media ensured something more permanent had been realized.

In his WSJ piece “Why This Tech Bubble Is Less Scary,” Chris Mims explains why this “frothy” period won’t be similar to the last one. Of particular interest is his analysis of tech companies floating on private money and what a market correction might mean to them. The opening:

Is tech in a bubble? I think so. The signs are all around us. The good news is, it’s nothing like the last one. Plus, for reasons that go beyond the usual impossibilities of economic prognostication, no one can say for sure what’s going on. Many people seem to find this reassuring, but we would be wise to heed the lesson that a lack of transparency about the mechanics of a market rarely leads anywhere good.

But first, let’s define what kind of a bubble tech might be in. It isn’t like the bubble of 1997-2000, the Kraken of legend that came from the depths to wreak havoc on the whole of the U.S. economy. That was a genuine, old-fashioned stock market bubble, with money pouring into publicly held tech companies that couldn’t justify the investment.

If I’m right, and what we’re experiencing now is a kind of Bubble Jr., any correction will be less widespread.

In 2015’s less-terrifying sequel to 1999, everyone is to be commended for avoiding the worst excesses of the past, the empty vehicles for irrational exuberance like Pets.com.•

Tags: Christopher Mims

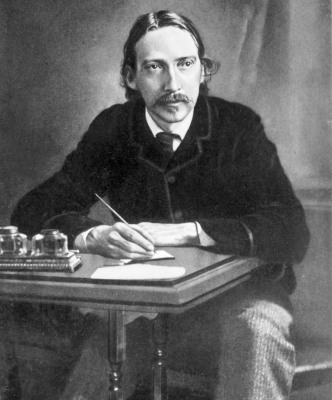

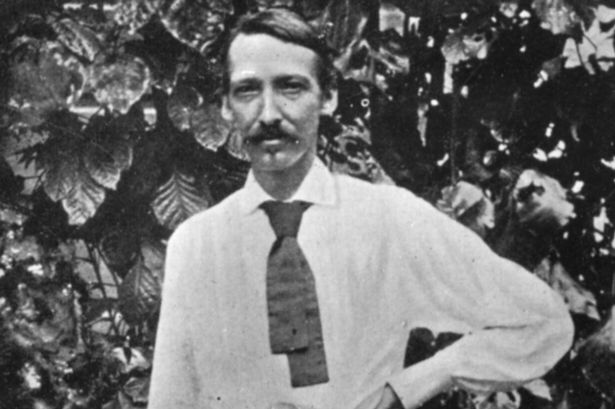

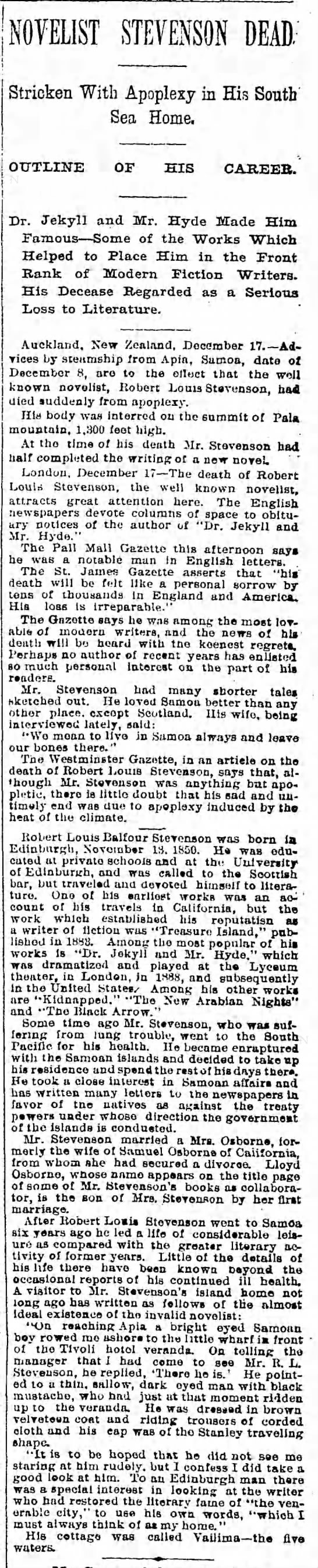

There was something rotten inside Robert Louis Stevenson, as there is in all of us, but he had a name for it: Mr. Hyde. Not to suggest the author’s voluminous and varied output can be reduced to one novella–I’m talking about the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, of course–but it’s rare that something can be written about the human mind, in this case the subconscious, that will be true as long there are people.

The following article from the December 17, 1894 Brooklyn Daily Eagle announced the sickly author’s death, which occurred two weeks earlier from a cerebral hemorrhage he experienced while living on the Samoan Islands.

Tags: Robert Louis Stevenson

In 1979, Thomas G. Stockham Jr., an electrical engineer who’d provided expert testimony on the Watergate tapes, was preaching to the recording industry that digital was the future, which ultimately helped convince execs to replace LPs with CDs. He spoke to Pattie Reilly of People magazine about the coming revolution, though even he didn’t seem to fully grasp the ramifications. An excerpt:

The pioneer in America in the new field is an MIT-trained electrical engineer and computer scientist named Thomas G. Stockham Jr. “Digital recording isn’t a fad,” he insists. “It’s a whole new concept, like a new alphabet. It has stunning implications. Digitals will cause a music revolution.”

The 45-year-old Stockham is making news with his Soundstream, Inc. of Salt Lake City. But he was no stranger to headlines before this: In 1974, during the Watergate investigation, he was one of six experts who testified on the 18½-minute gap in the Nixon tapes. He and the others agreed that the segment of conversation between the ex-President and aide H. R. Haldeman had been erased from five to nine times, although they stopped short of saying that the so-called accidental erasure was apparently deliberate.

In 1975 Stockham left his professorship at the University of Utah to set up Soundstream, which built the first successful digital recorder in the U.S. the next year. Since then other companies, like 3M and Sony, have developed rival digital systems independently.

Today Soundstream is producing digitally recorded discs for 11 record companies, and the LPs are being sold at selected stores. Though the discs look the same as conventional ones, they can be identified by the word “digital” stamped on the jacket and by their premium prices, ranging from $11 to $18. …

Without doubt, digital recording enhances the reproduction of almost any orchestral performance and that of soloists with multidimensional voices. Another plus is that the new discs can be played on ordinary stereos, and the improvement is obvious even with a basic $400 system. While digitals will not necessarily make conventional records obsolete, the question is whether fussy listeners will want to play their old library after hearing digitals.”•

Thomas Piketty is a capitalist, which might surprise some. The French economist simply believes the system is a driving force of wealth inequality if left unfettered and must be constantly treated, like a patient prone to fever. In a Financial Times piece by Anne-Sylvaine Chassany, Piketty discusses the development of his ideas. An excerpt:

Piketty says his interest in inequality crystallised after the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the first Gulf war. He recalls visiting Moscow in 1991 and being struck by “the lines in front of shops”. He came back vaccinated against communism — “I believe in capitalism, private property, the market” — but also with a question central to his work: “How come those people had been so afraid of inequality and capitalism in the 19th and 20th century that they created such a monstrosity? How can we tackle inequality without repeating this disaster?”

The first Gulf war, he believed, demonstrated the cynicism of the west: “We are told constantly that states can’t do anything, that it’s impossible to regulate the Cayman Islands and the other tax havens because they are too powerful, and all of a sudden we send a million soldiers 10,000km from home to allow the emir of Kuwait to keep his oil.”

I am halfway through the now tepid bolognese when I ask him why his work had such an impact in the US without causing anything like such a stir in France at the time of its original publication. Piketty says he caught American attention in 2003 when, together with Emmanuel Saez, a fellow French economist who teaches at the University of California, he first compiled historical data on the US’s wealthiest people. In 2009, newly elected President Obama used the French economists’ graph that showed inequality was back to its 1929 peak. “We became the target of Republican think-tanks,” he recalls. The French version of the book acted as a teaser to those critics, he believes, helping propel it to the top of Amazon’s bestseller list for three weeks when it was released in English.

“The rise of the top 1 per cent is an American thing. It’s not by chance that Occupy Wall Street happened in Wall Street, and not in Brussels, Paris or Tokyo,” he says. “It’s different in Europe. Here, inequality takes the form of unemployment and public debt.”

Though Piketty concedes that the global wealth tax he recommends is a “utopian” dream, he also says a confiscatory tax rate of more than 80 per cent on earnings exceeding $1m would work.•