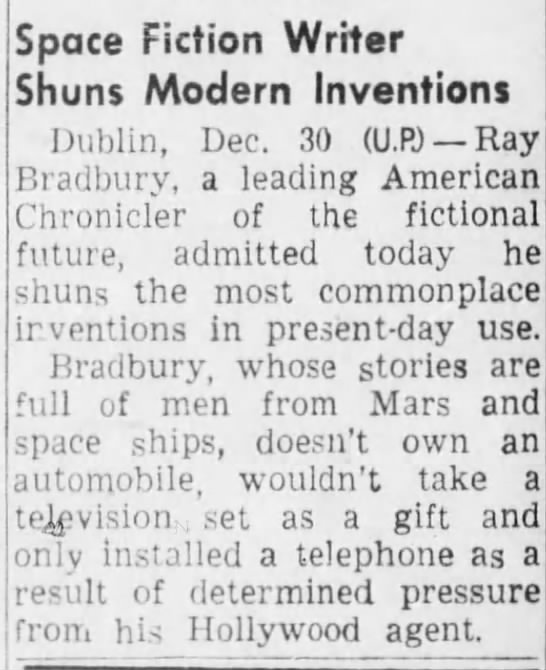

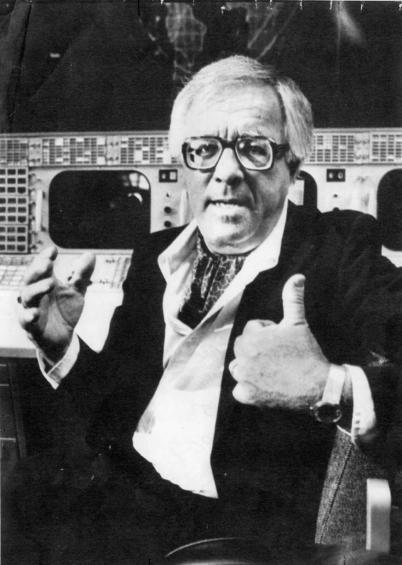

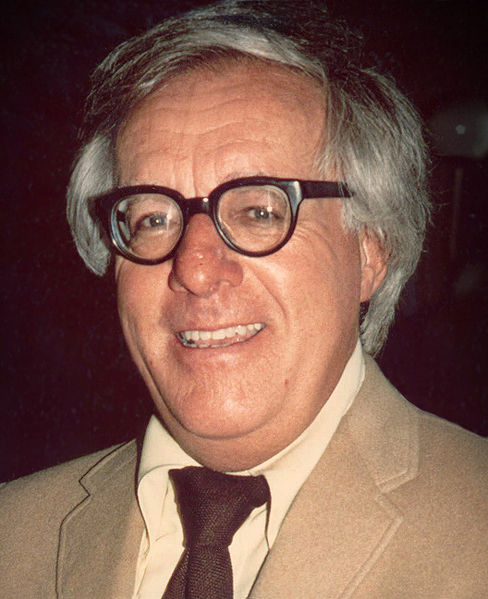

Just read “Far-Distant Days,” Ben Thomas’ very good Aeon essay about the often-vertiginous reality of the deep past, which may be discomfiting to face but must be confronted should we hope to manage today and tomorrow’s challenges. In the opening, Thomas draws on Ray Bradbury’s 1965 essay “The Machine-Tooled Happyland,” which was inspired by his long-simmering anger over Julian Halevy’s decidedly negative 1955 Nation review of Disneyland’s opening.

Halevy identified Walt’s new theme park and its far more raffish cousin Las Vegas as twin examples of vulgar American escapism that was being driven by mounting conformity. This road to nowhere—or at least to un-realism—became eminently more crowded in the decades that followed with the emergence of Graceland, Comic-Con, Dungeons & Dragons, the Internet, Netflix, Facebook, Reality TV, cosplay, Virtual Reality, Pokémon Go and, finally, a garbage-mouthed game show host for a President. Halevy’s concluding sentences:

I’m writing about Disneyland and Las Vegas to make another point: that both these institutions exist for the relief of tension and boredom, as tranquilizers for social anxiety, and that they both provide fantasy experiences in which not-so-secret longings are pseudo-satisfied. Their huge profits and mushrooming growth suggest that as conformity and adjustment become more rigidly imposed on the American scene, the drift to fantasy relief will become a flight. So make your reservations early.•

“The drift to fantasy relief will become a flight,” may be the most ominous and truest prediction made in mid-century America.

One decade later, Bradbury, whose devotion to Disney was rivaled only by Charles Laughton’s—the actor-director was the one who first introduced the sci-fi legend to the theme park—struck back at Halevy in his response in Holiday. More puzzling than the writer’s unbridled appreciation for Disney’s still-crude animatronics in a time when real rockets were traveling through space, were his views on the future of history. Bradbury believed machines in “audio-animatronic museums” could make the inscrutable past uniform, could bring it to life. He wrote: “One problem of man is believing in his past.”

When he asserts that in 2065 “Caesar, computerized, [will] speak in the Forum,” he was unwittingly describing Virtual Reality far more than robotics. He believed new tools would finally get humanity on the same page, that history would be taught by robotics that were controlled by a seer like Disney, not fully comprehending a decentralized age would allow for the remixing and distorting of history on an epic scale, and that all of it, even slavery and the Holocaust, could be reduced to entertainment or worse.

Bradbury did, however, have some inkling of the potential pitfalls, writing: “Am I frightened by any of this? Yes, certainly. For these audio-animatronic museums must be placed in hands that will build the truths as well as possible, and lie only through occasional error.”

The full essay:

“THE MACHINE-TOOLED HAPPYLAND”

The wondrous devices of Disneyland take on startling importance in the mind of a science fiction seer

Two thousand years back, people entering Grecian temples dropped coins into machinery that then clanked forth holy water.

It is a long way from that first slot machine to the “miracles of rare device” created by Walt Disney for his kingdom, Disneyland. When Walt Whitman wrote, “I sing the Body Electric,” he little knew he was guessing the motto of our robot-dominated society. I believe Disney’s influence will be felt centuries from today. I say that Disney and Disneyland can be prime movers of our age.

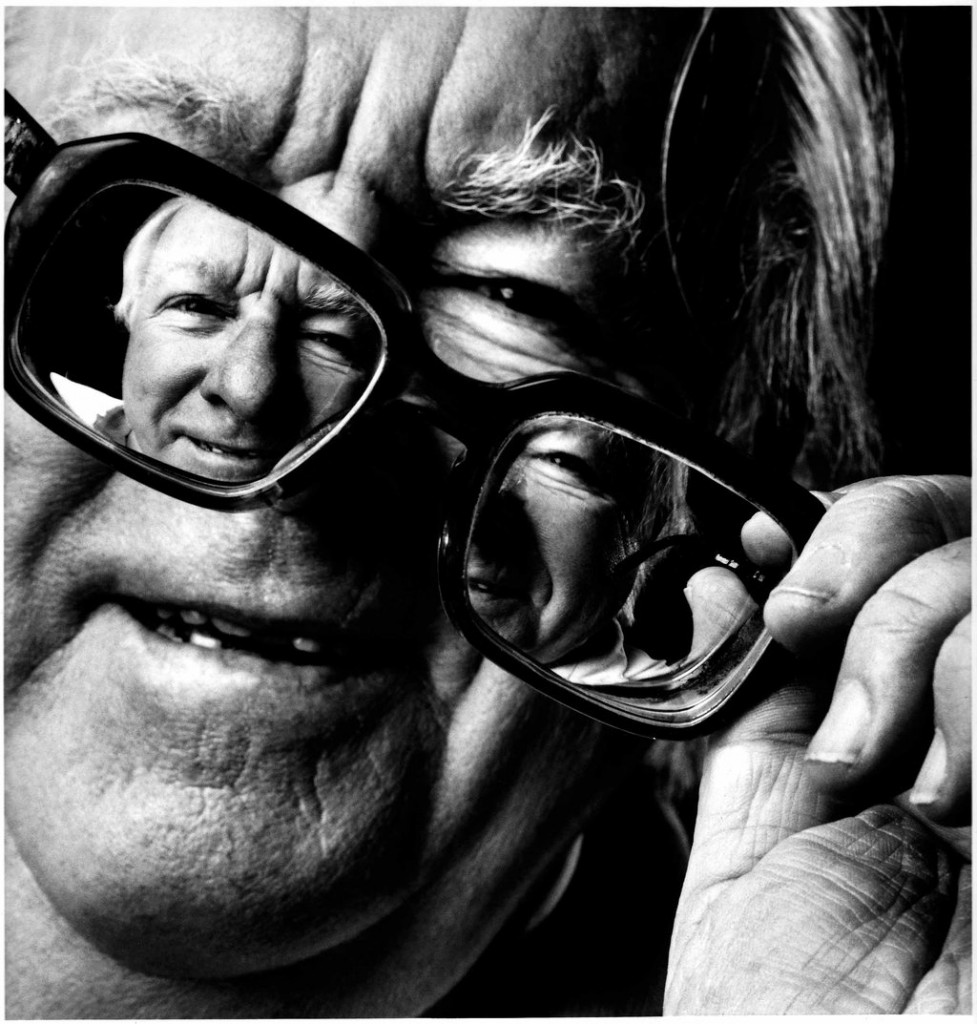

But before I offer proof, let me sketch my background. At twelve, I owned one of the first Mickey Mouse buttons in Tucson, Arizona. At nineteen, selling newspapers on a street corner, I lived in terror I might be struck by a car and killed before the premiere of Disney’s film extravaganza, Fantasia. In the last thirty years I have seen Fantasia fifteen times, Snow White twelve times, Pinocchio eight times. In sum, I was, and still am, a Disney nut.

You can imagine, then, how I regarded an article in the Nation some years ago that equated Disneyland with Las Vegas. Both communities, claimed the article, were vulgar, both represented American culture at its most corrupt, vile and terrible.

I rumbled for half an hour, then exploded. I sent a letter winging to the prim Nationeditors.

“Sirs,” it said, “like many intellectuals before me I delayed going to Disneyland, having heard it was just too dreadfully middle-class. One wouldn’t dream of being caught dead there.

“But finally a good friend jollied me into my first grand tour of the Magic Kingdom. I went…with one of the great children of our time: Charles Laughton.”

It is a good memory, the memory of the day Captain Bligh dragged me writhing through the gates of Disneyland. He plowed a furrow in the mobs; he surged ahead, one great all-enveloping presence from whom all fell aside. I followed in the wake of Moses as he bade the waters part, and part they did. The crowds dropped their jaws and, buffeted by the passage of his immense body through the shocked air, spun about and stared after us.

We made straight for the nearest boat—wouldn’t Captain Bligh?—the Jungle Ride.

Charlie sat near the prow, pointing here to crocodiles, there to bull elephants, farther on to feasting lions. He laughed at the wild palaver of our riverboat steersman’s jokes, ducked when pistols were fired dead-on at charging hippopotamuses, and basked face up in the rain, eyes shut, as we sailed under the Schweitzer Falls.

We blasted off in another boat, this one of the future, the Rocket to the Moon. Lord, how Bligh loved that.

And at dusk we circuited the Mississippi in the Mark Twain, with the jazz band thumping like a great dark heart, and the steamboat blowing its forlorn dragon-voice whistle, and the slow banks passing, and all of us topside, hands sticky with spun candy, coats snowed with popcorn salt, smiles hammer-tacked to our faces by one explosionof delight and surprise after another.

Then, weary children, Charlie the greatest child and most weary of all, we drove home on the freeway.

That night I could not help but remember a trip East when I got of a Greyhound in Las Vegas at three in the morning. I wandered through the mechanical din, through clusters of feverish women clenching robot devices, Indian-wrestling them two falls out of three. I heard the dry chuckle of coins falling out of chutes, only to be reinserted, redigested and lost forever in the machinery guts.

And under the shaded lights, the green-visored men and women dealing cards, dealing cards, noiselessly, expressionlessly, numbly, with viper motions, flicking chips, rolling dice, taking money, stacking chips—showing no joy, no fun, no love, no care, unhearing, silent and blind. Yet on and on their hands moved. The hands belonged only to themselves. While across from these ice-cold Erector-set people, I saw the angered lust of the grapplers, the snatchers, the forever losing and the always lost.

I stayed in Dante’s Las Vegas Inferno for one hour, then climbed back on my bus, taking my soul locked between my ribs, careful not to breathe it out where someone might snatch it, press it, fold it and sell it for a two-buck chip.

In sum, if you lifted the tops of the Las Vegas gamblers’ craniums you would find watch cogs, black hairsprings, levers, wheels in wheels all apurr and agrind. Tap them, they’d leak lubricant. Bang them, they’d bell like aluminum tambourines. Slap their cheeks and a procession of dizzy lemons and cherries would fly by under their cocked eyelids. Shoot them and they’d spurt nuts and bolts.

Vegas’s real people are brute robots, machine-tooled bums.

Disneyland’s robots are, on the other hand, people, loving, caring and eternally good.

Essence is everything.

What final point do I choose to make in the comparison? It is this: we live in an age of one billion robot devices that surround, bully, change and sometimes destroy us. The metal-and-plastic machines are all amoral. But by their design and function they lure us to be better or worse than we might otherwise be.

In such an age it would be foolhardy to ignore the one man who is building human qualities into robots—robots whose influence will be ricocheting off social and political institutions ten thousand afternoons from today.

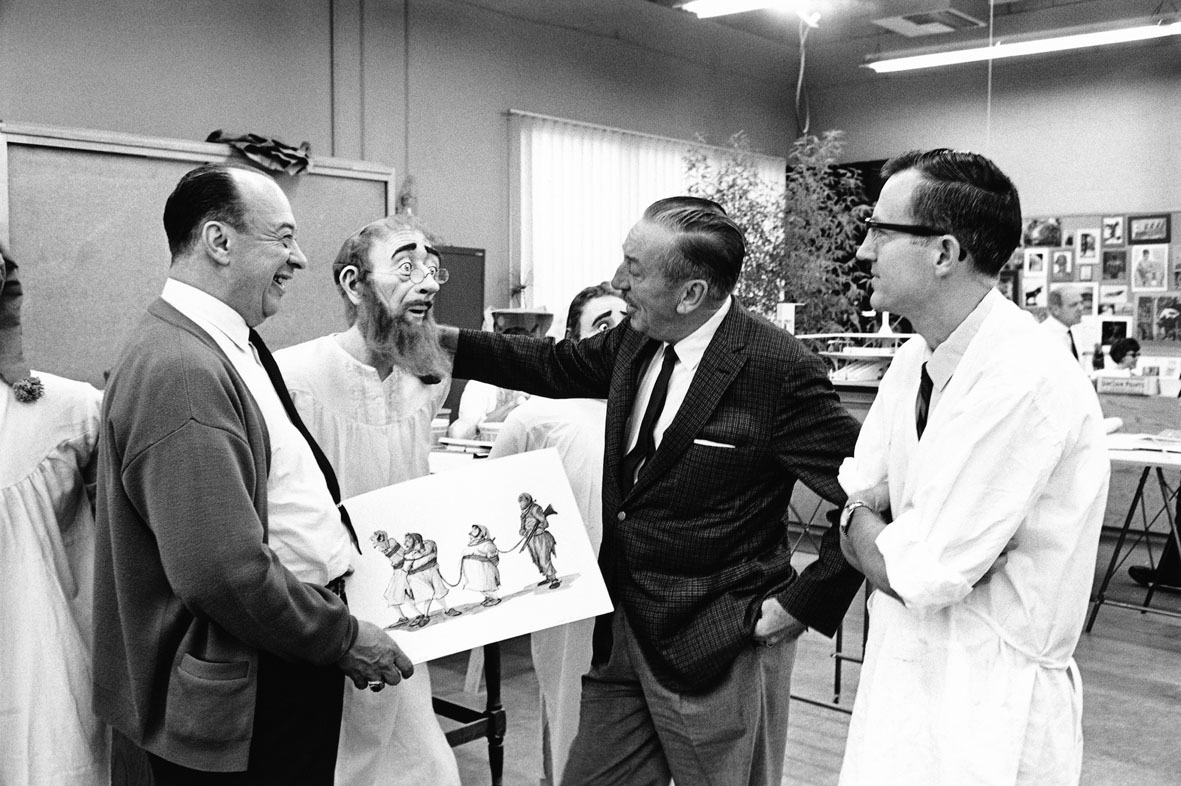

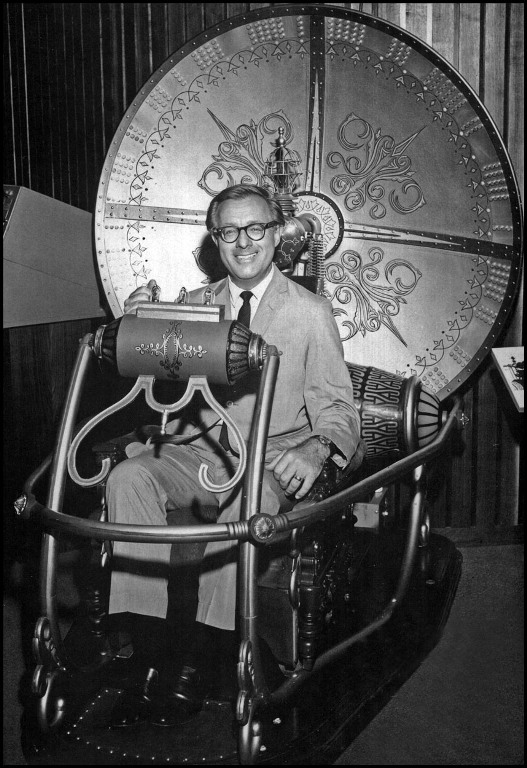

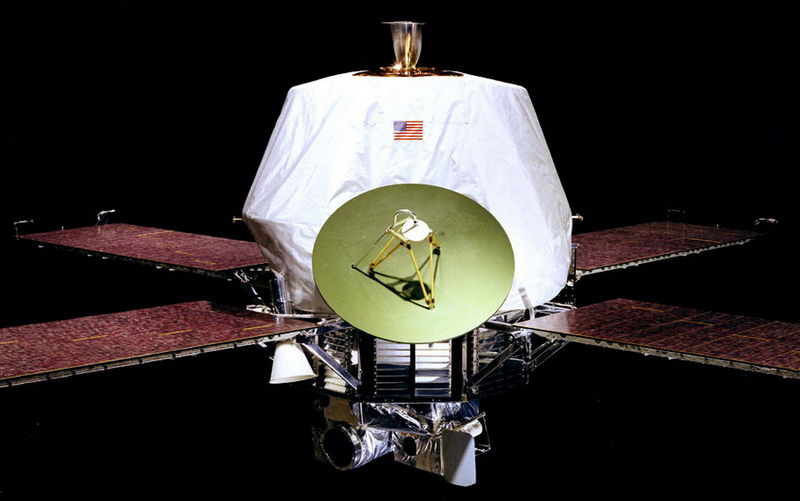

Snobbery now could cripple our intellectual development. After I had heard too many people sneer at Disney and his audio-animatronic Abraham Lincoln in the Illinois exhibit at the New York World’s Fair, I went to the Disney robot factory in Glendale. I watched the finishing touches being put on a second computerized, electric- and air-pressure-driven humanoid that will “live” at Disneyland from this summer on. I saw this new effigy of Mr. Lincoln sit, stand, shift his arms, turn his wrists, twitch his fingers, put his hands behind his back, turn his head, look at me, blink and prepare to speak. In those few moments I was filled with an awe I have rarely felt in my life.

Only a few hundred years ago all this would have been considered blasphemous, I thought. To create man is not man’s business, but God’s, it would have been said. Disney and every technician with him would have been bundled and burned at the stake in 1600.

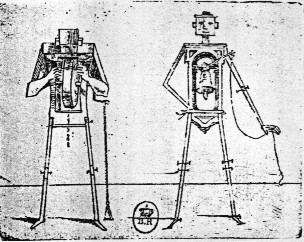

And again, I thought, all of this was dreamed before. From the fantastic geometric robot drawings of Bracelli in 1624 to the mechanical people in Capek’s R.U.R. in 1925, others have conceived and drawn metallic extensions of man and his senses, or played at it in theater.

But the fact remains that Disney is the first to make a robot that is convincingly real, that looks, speaks and acts like a man. Disney has set the history of humanized robots on its way toward wider, more fantastic excursions into the needs of civilization.

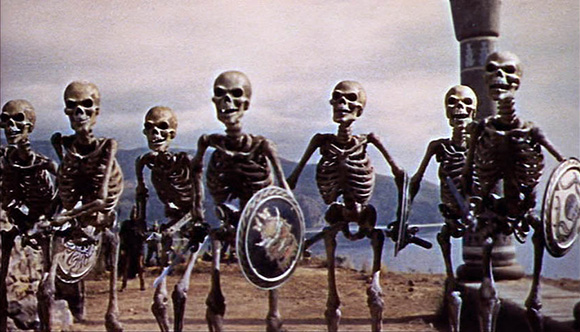

Send your mind on to the year 2065. A mere century from now set yourself down with a group of children entering an audio-animatronic museum. Inside, you find the primal sea from which we swam and crawled up on the land. In that sea, the lizard beasts that tore the air with strange cries for a million on a million years. Robot animals feasting and being feasted upon as robot apeman waits in the wings for the nightmare blood to cease flowing.

Farther on you see robot cavemen frictioning fire into existence, bringing a mammoth down in a hairy avalanche, curing pelts, drawing quicksilver horse flights like flashes of motion pictures on cavern walls.

Robot Vikings treading the Vinland coastal sands.

Caesar, computerized, speaks in the Forum. falls in the Senate, lies dead and perfect as Antony declaims over his body for the ten-thousandth time.

Napoleon, ticking as quietly as a clockshop, at Waterloo.

Generals Grant and Lee alive again at Appomattox.

King John, all hums and oiled whirs at Runnymede, signing Magna Charta.

Fantastic? Perhaps. Ridiculous? Somewhat. Nonsensical? Vulgar? A touch. Not worth the doing? Worth doing a thousand times over.

For one problem of man is believing in his past.

We have had to take on faith the unproven events of unproven years. For all the reality of ruins and scrolls and tablets, we fear that much of what we read has been made up. Artifacts may be no more than created symbols, artificial skeletons thrown together to fit imaginary closets. The reality, even of the immediate past, is irretrievable.

Thus, through half belief, we are often doomed to repeat that very past we should have learned from.

But now through audio-animatronics, robot mechanics, or if you prefer, the science of machines leaning their warm shadows toward humanity, we can grasp and fuse the best of two art forms.

Motion pictures suffer from not being “real” or three-dimensionally present. Their great asset is that they can be perfect. That is, a director of genius can shoot, cut, reshoot, edit and re-edit his dream until it is just the way he wants it. His film, locked in a time capsule and opened five centuries later, would still contain his ideal in exactly the form he set for it.

The theater suffers from a reverse problem. Live drama is indeed more real, it is “there” before you in the flesh. But it is not perfect. Out of thirty-odd performances a month, only once, perhaps, will all the actors together hit the emotional peak they are searching for.

Audio-animatronics borrows the perfection of the cinema and marries it to the “presence” of stage drama.

To what purpose?

So that at long last we may begin to believe in every one of man’s many million days upon this Earth.

Emerging from the robot museums of tomorrow, your future student will say: I know, I believe in the history of the Egyptians, for this day I helped lay the cornerstone of the Great Pyramid.

Or, I believe Plato actually existed, for this afternoon under a laurel tree in a lovely country place I heard him discourse with friends, argue by the quiet hour; the building stones of a great Republic fell from his mouth.

Now at last see how Hitler derived his power. I stood in the stadium at Nuremberg, I saw his fists beat on the air, I heard his shout and the echoing shout of the mob and the ranked armies. For some while I touched the living fabric of evil. I knew the terrible and tempting beauty of such stuffs. I smelled the torches that burned the books. I turned away and came out for air…. Beyond, in that museum, lies Belsen, and beyond that, Hiroshima…. Tomorrow I will go there.

For these students it will not be history was but history is.

Not Aristotle lived and died, but Aristotle is in residence this very hour, just down the way.

Not Lincoln’s funeral train forever lost in the crepe of time, but Lincoln eternally journeying from Springfield to Washington to save a nation.

Not Columbus sailed but Columbus sails tomorrow morning; sign up, take ship, go along.

Not Cortez sighted Mexico, but Cortez makes landfall at 3 P.M. by the robot museum clock. This instant, Montezuma waits to be wound-up and sent on his way.

Perhaps out of all this fresh seeing and knowing will come such understanding as will stop our cycling round to repeat our past.

Do I make too much of this? Perhaps. Nothing is guaranteed. We are wandering in the childhood of machines. When we and the machines mature, who can say what we might accomplish together?

Am I frightened by any of this? Yes, certainly. For these audio-animatronic museums must be placed in hands that will build the truths as well as possible, and lie only through occasional error. Otherwise we shall end in the company of Baron Frankenstein and some AC-DC Genghis Khan.

The new appreciation of history begins with the responsibility in the hands of a man I trust, Walt Disney. In Disneyland he has proven again that the first function of architecture is to make men over make them wish to go on living, feed them fresh oxygen, grow them tall, delight their eyes, make them kind.

Disneyland liberates men to their better selves. Here the wild brute is gently corralled, not wised and squashed, not put upon and harassed, not tromped on by real-estate operators, nor exhausted by smog and traffic.

What works at Disneyland should work in the robots that Disney, and others long after him, invent and send forth upon the land.

I rest my case by sending you at your next free hour to Disneyland itself. There you will collect your own evidence. There you will see the happy faces of people.

I don’t mean dumb-cluck happy, I don’t mean men’s-club happy or sewing-circle happy. I mean truly happy.

No beatniks here. No Cool people with Cool faces pretending not to care, thus swindling themselves out of life or any chance for life.

Disneyland causes you to care all over again. You feel it is that first day in the spring of that special year when you discovered you were really alive. You return to those morns in childhood when you woke and lay in bed and thought, eyes shut, “Yes, sir, the guys will be here any sec. A pebble will tap the window, a dirt clod will horse-thump the roof, a yell will shake the treehouse slats.”

And then you woke fully and the rock did bang the roof and the yell shook the sky and your tennis shoes picked you up and ran you out of the house into living.

Disneyland is all that. I’m heading there now. Race you?•