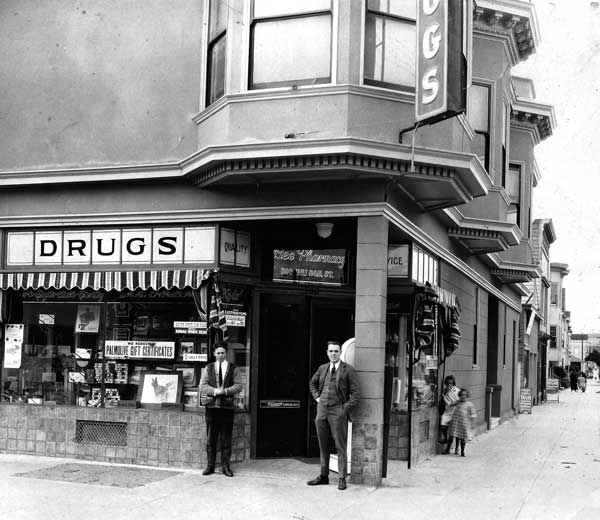

I don’t use illegal drugs, and I don’t think you should, either. They’re bad for you. But that doesn’t mean I support any cockamamie “War on Drugs.” That’s just bad policy crashing into stark reality. I think if someone sells drugs to a minor, they should be given a prison sentence. Otherwise, the whole thing should be decriminalized. That doesn’t mean it should be legalized. Relatively mild substances like marijuana should be legal and arrests for other harder drugs should be met with out-patient rehab and community-service sentences, for both dealers and buyers.

Of course, the situation is further complicated because you don’t have to do anything illegal to get a dangerous high. The number of Americans attaining painkillers, Oxy and others, with prescriptions is staggering. I don’t doubt these folks have pain, though usually it’s more mental than physical. The pusher got pushed by Big Pharma, and attempting to cage that monster will only cause more problems, especially with the Internet opening up global sales far too large to be prosecuted with precision.

Mike Jay, who wrote this brilliant article for Aeon last year, returns to the same publication with a piece that doesn’t try to make sense of this unwinnable war but to show how senseless it is in the light of history and the new normal. The opening:

“When the US President Richard Nixon announced his ‘war on drugs’ in 1971, there was no need to define the enemy. He meant, as everybody knew, the type of stuff you couldn’t buy in a drugstore. Drugs were trafficked exclusively on ‘the street’, within a subculture that was immediately identifiable (and never going to vote for Nixon anyway). His declaration of war was for the benefit the majority of voters who saw these drugs, and the people who used them, as a threat to their way of life. If any further clarification was needed, the drugs Nixon had in his sights were the kind that was illegal.

Today, such certainties seem quaint and distant. This May, the UN office on drugs and crime announced that at least 348 ‘legal highs’ are being traded on the global market, a number that dwarfs the total of illegal drugs. This loosely defined cohort of substances is no longer being passed surreptitiously among an underground network of ‘drug users’ but sold to anybody on the internet, at street markets and petrol stations. It is hardly a surprise these days when someone from any stratum of society – police chiefs, corporate executives, royalty – turns out to be a drug user. The war on drugs has conspicuously failed on its own terms: it has not reduced the prevalence of drugs in society, or the harms they cause, or the criminal economy they feed. But it has also, at a deeper level, become incoherent. What is a drug these days?

Consider, for example, the category of stimulants, into which the majority of ‘legal highs’ are bundled. In Nixon’s day there was, on the popular radar at least, only ‘speed’: amphetamine, manufactured by biker gangs for hippies and junkies. This unambiguously criminal trade still thrives, mostly in the more potent form of methamphetamine: the world knows its face from the US TV series Breaking Bad, though it is at least as prevalent these days in Prague, Bangkok or Cape Town. But there are now many stimulants whose provenance is far more ambiguous.

Pharmaceuticals such as modafinil and Adderall have become the stay-awake drugs of choice for students, shiftworkers and the jet-lagged: they can be bought without prescription via the internet, host to a vast and vigorously expanding grey zone between medical and illicit supply. Traditional stimulant plants such as khat or coca leaf remain legal and socially normalised in their places of origin, though they are banned as ‘drugs’ elsewhere. La hoja de coca no es droga! (the coca leaf is not a drug) has become the slogan behind which Andean coca-growers rally, as the UN attempts to eradicate their crops in an effort to block the global supply of cocaine. Meanwhile, caffeine has become the indispensable stimulant of modern life, freely available in concentrated forms such as double espressos and energy shots, and indeed sold legally at 100 per cent purity on the internet, with deadly consequences. ‘Legal’ and ‘illegal’ are no longer adequate terms for making sense of this hyperactive global market.”