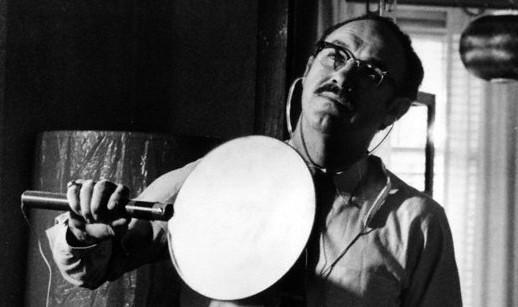

In 1976, Gail Jennes of People magazine conducted a Q&A with Michael L. Dertouzos, who was the Director of the Laboratory for Computer Science at MIT. He pretty much hit the bullseye on everything regarding the next four decades of computing, except for thinking Moore’s Law would reach endgame in the mid-’80s. An excerpt:

Question:

Could a computer ever become as “human” as the one named Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey?

Michael Dertouzos:

A computer has already taken over a “human” mission on the Viking mission to Mars. But control over humans is a different issue. In open-heart surgery where a computer monitors bloodstream and vital functions, are we not under a machine’s control? A human being is often under the control of a machine and, in many situations, wants to be.

Question:

Will machines ever be more intelligent than humans?

Michael Dertouzos:

That is the important question, and the one on which scientists are split. One side says it’s impossible to make machines with the same intelligence, emotions and abilities as humans, and that therefore machines will only be able to do our bidding. The other side believes that it’s possible to make machines learn much more. Both sides argue from faith; neither from fact.

Question:

What do you think?

Michael Dertouzos:

I think progress will be a lot slower than predicted. Computers will get smarter gradually. I don’t know if they will get as smart as we are. If they did, it probably would take a long time. …

Question:

Will computers be widely used by the average person in coming years?

Michael Dertouzos:

We don’t see technical limitations in computer development until the mid-1980s. Until then, decreased cost will make computers smaller, cheaper and more accessible. In 10 or 15 years, one should cost about the same as a big color TV. This machine could become a playmate, testing your wits at chess or checkers. If a computer were hooked up to AP or UPI news-wires, it could be programmed to know that I’m interested in Greece, computers and music. Whenever it caught news items about these subjects, it would print them out on my console—so I would see only the things I wanted to see.

Question:

Will they transmit mail?

Michael Dertouzos:

We are already hooked into a network spanning the U.S. and part of Europe by which we send, collect and route messages easily. Although the transmission process is instant, you can let messages pile up until you turn on your computer and ask for your mail.

Question:

Will the computer eventually be as common as the typewriter?

Michael Dertouzos:

Perhaps even more so. It may be hidden so you won’t even know you’re using it. Don’t be surprised if there is one in every telephone, taking over most of the dialing. If you want to call your friend Joe, you just dial “JOE.” The same machine could take messages, advise if they were of interest and then could ring you. In the future, I would imagine there could be computerized cooking machines. You put in a little card that says Chateaubriand and it cooks the ingredients not only according to the best French recipe, but also to your particular taste.

Question:

Will robots ever be heavily relied upon?

Michael Dertouzos:

Robots are already doing things for us—for example, accounting and assembling cars. Two-legged robotic bipeds are a romantic notion and actually pretty unstable. But computer-directed robot machines with wheels, for example, may eventually do the vacuum cleaning and mow the lawn.

Question:

How might computers aid us in an election year?

Michael Dertouzos:

Voters might quickly find out political candidates’ positions on the issues by consulting computers. Government would then be closer to the pulse of the governed. If we had access to a very intelligent computer, we could probe to find out if the guy is telling the truth by having them check for inconsistency—but that is way in the future.

Question:

Should everyone be required to take a computer course?

Michael Dertouzos:

I’d rather see people choose to do so. Latin, the lute and the piano used to be required as a part of a proper upbringing. Computer science will be thought of in the same way. If we can use the computer early in life, we can understand it so we won’t be hoodwinked into believing it can do the impossible. A big danger is deferring to computers out of ignorance.•