Really wonderful conversation between Sean Illing of Vox and the economist Tyler Cowen, whose thinking I always admire even when I disagree with him. The two discuss, among other topics, the Internet, biotech, politics, war, Kanye West and the “most dangerous idea in history.” An excerpt:

Question:

How do you view the internet and its impact on human life?

Tyler Cowen:

The internet is great for weirdos. The pre-internet era was not very good for weirdos. I think in some ways we’re still overrating the internet as a whole. It’s wonderful for manipulating information, which appeals to the weirdos. Now it’s going to start changing our physical reality in a way that will be another productivity boom. So I’m very pro-internet.

Question:

What do you think will be the next major technological breakthrough?

Tyler Cowen:

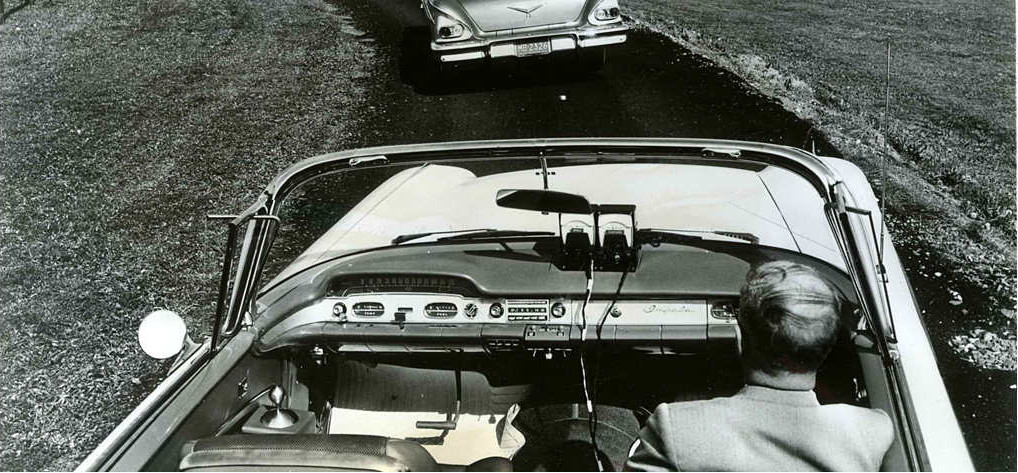

If you mean a single thing that you could put in a single headline, I would say self-driving vehicles. But I think a deeper and more important thing will be a subtle integration of software and hardware in way that will change everything and won’t have a single name.

Question:

Are you thinking here of the singularity or of something less radical?

Tyler Cowen:

No, nothing like the singularity. But software embedded in devices that will get better and smarter and more interactive and thoughtful, and we’ll be able to do things that we’ll eventually take for granted and we won’t even call them anything.

Question:

Do you think technology is outpacing our politics in dangerous, unpredictable ways?

Tyler Cowen:

Of course it is. And the last time technology outpaced politics, it ended in a very ugly manner, with two world wars. So I worry about that. You get new technologies. People try to use them for conquest and extortion. I’ve no predictions as to how that will play out, but I think there’s at least a good chance that we will look back on this era of relative technological stagnancy and say, “Wasn’t that wonderful?”•