“The brain, like the phonographic cylinder, is a mere record.”

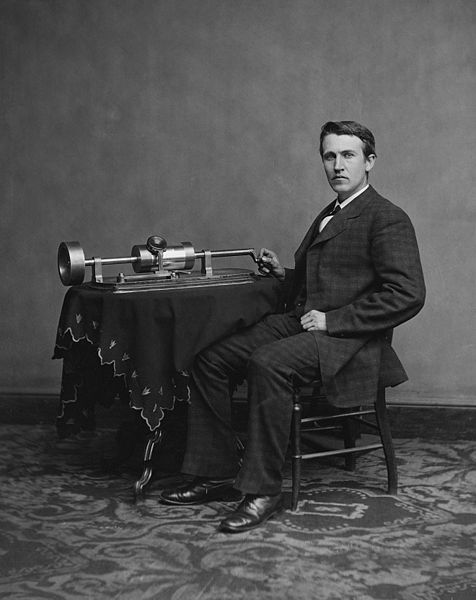

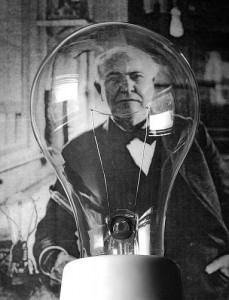

Thomas Edison didn’t believe humans were magical, individual souls created by God but simply a swarm of biological machines. The death of philosopher William James in 1910 occasioned much breathless discussion in intellectual circles about immortality and heaven, but Edison wasn’t having any of it. From an article by Edward Marshall in the October 2, 1910 New York Times:

“No one has studied the minutiae of science with greater care than Edison. I determined, therefore, to find out what were his conclusions. And the result, as I have said, was amazing, fascinating.

Searching the inner structure of all things for the fundamental. Edison told me he had come to the conclusion that there were is no ‘supernatural,’ or ‘supernormal,’ as the psychic researchers put it–that all there is, that all there has been, all there ever will be, soon or late, be explained among the material lines.

He denied the individuality of the human being, declaring that each human being is an aggregate, as a city is an aggregate. No just judge would, in these modern days of clearing vision, punish or reward an entire city full; therefore future reward and punishment for human beings seems to him unreasonable. Immortality of the human soul seems as unreasonable. He does not, indeed, admit existence of a soul.

A merciful and loving creator he considers not to be believed in. Nature, the supreme power, he recognizes and respects, but does not worship. Nature is not merciful and loving, but wholly merciless, indifferent. He hints, but does not say, that he believes discoveries of vast import will be made by man among the hidden mysteries of life, but thinks the present wave of ‘psychic study’ is conducted on wrong lines–lines which are so utterly at fault that it is most unlikely they ever will produce important information.

‘I cannot believe in the immortality of the soul,’ he said to me, as, with his eyes closed tightly while concentrated in deep thought, he sat the other day in the great, dim library which forms his private quarters in the tremendous works known as his ‘laboratory’ at Orange, N.J.

‘Heaven? Shall I, if I am good and earn reward, go to heaven when I die? No–no. I am not I–I am not an individual–I am an aggregate of cells, as for instance, New York City is an aggregate of individuals. Will New York City go to heaven?’

The perfecter of the telegraph, inventor of the megaphone, the phonograph, the aerophone, the incandescent lamp and lighting system, and more than 700 other things, raised his massive head and looked at me with eyes which did not see me because the mind behind them was busy searching the vast mysteries of our existence.

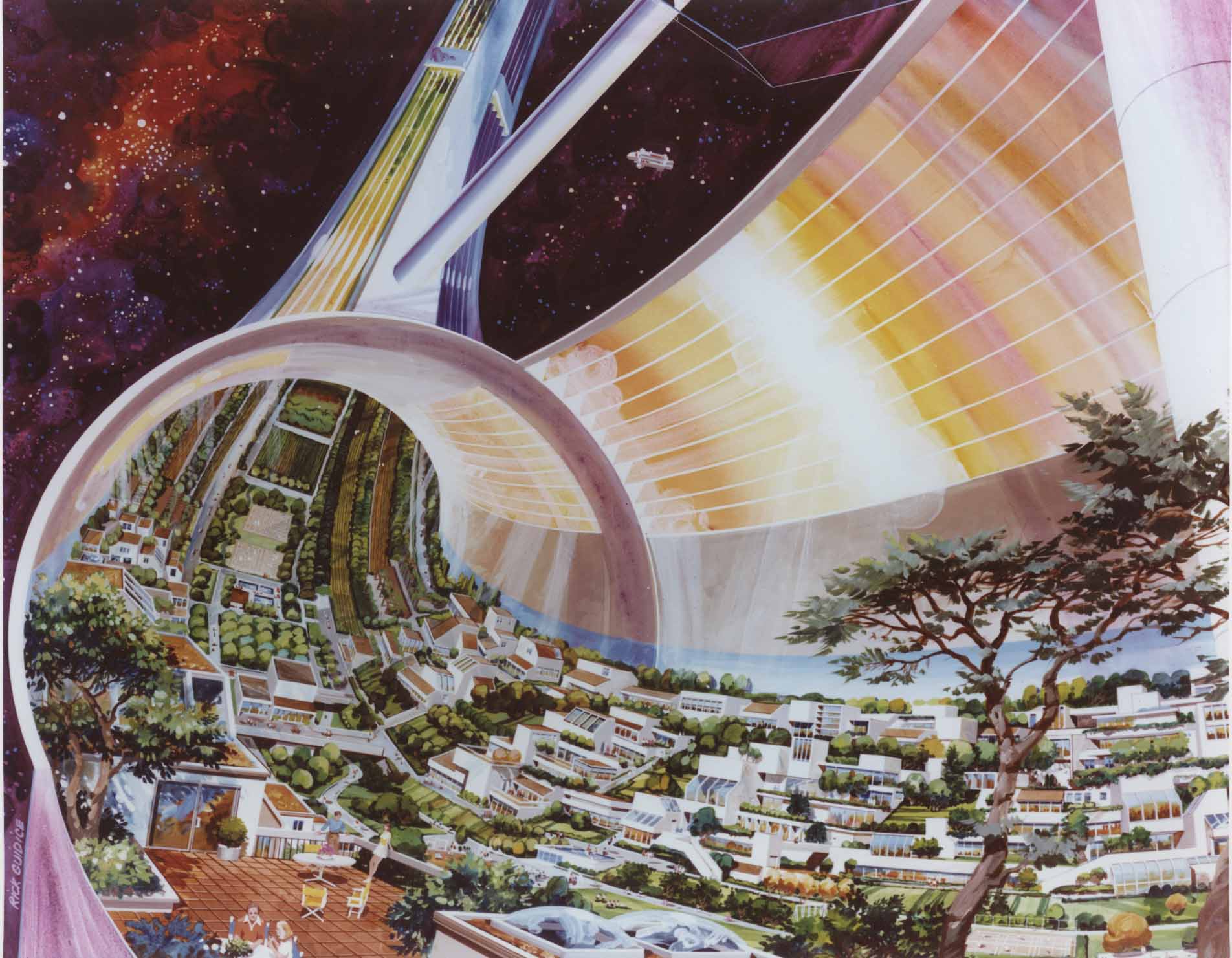

‘I do not think that we are individuals at all,’ he went on slowly. ‘The illustration I have used is good. We are not individuals any more than a great city is an individual.

‘I do not think that we are individuals at all,’ he went on slowly. ‘The illustration I have used is good. We are not individuals any more than a great city is an individual.

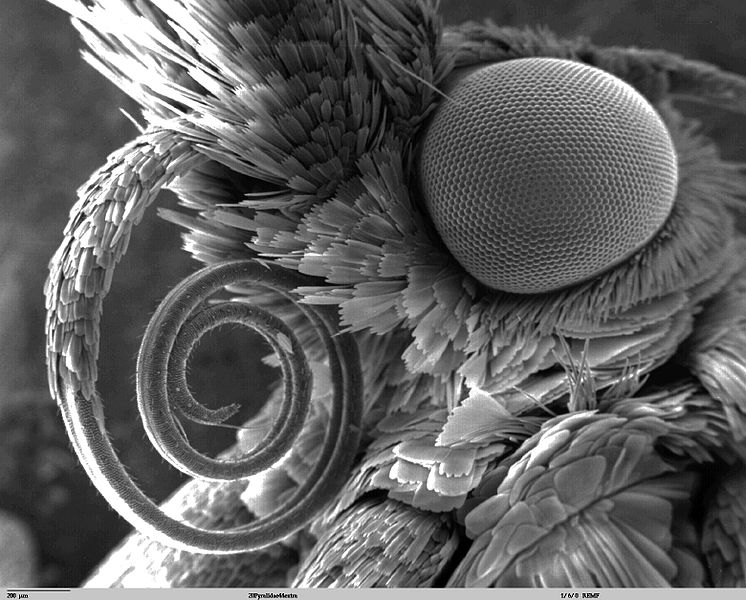

‘If you cut your finger and it bleeds, you lose cells. They are the individuals. You don’t know them–you don’t know your cells any more than New York City knows its five millions of inhabitants. You don’t know who they are.

‘No, all this talk of an existence for us, as individuals, beyond the grave is wrong. It is born of our tenacity of life–our desire to go on living–our dread of coming to an end as individuals. I do not dread it though. Personally I cannot see any use of a future life.

‘But the soul!’ I protested. The soul–‘

‘Soul? Soul? What do you mean by soul? The brain?’

‘Well, for the sake of argument, call it the brain, or what is in the brain. Is there not something immortal of or in the human brain–the human mind?’

‘Absolutely no,’ he said with emphasis. ‘There is no more reason to believe that any human brain will be immortal than there is to think that one of my phonographic cylinders will be immortal. My phonographic cylinders are mere records of sounds which have been impressed upon them.

Under given conditions, some of which we do not at all understand, any more than we understand some of the conditions of the brain, the phonographic cylinders give off these sounds again. For the time being we have perfect speech, or music, practically as perfect as is given off by the tongue when the necessary forces are set in motion by the brain.

‘Yet no one thinks of claiming immortality for the cylinders or the phonograph. Then why claim it for the brain mechanism or the power that drives it? Because we don’t know what this power is, shall we call it immortal? As well call electricity immortal because we do not know what it is.

‘The brain, like the phonographic cylinder, is a mere record, not of sounds alone, but of other things which have been impressed upon it by the mysterious power which actuates it. Perhaps it would be better if we called it a recording office, where records are made and stored. But no matter what you call it, it is a mere machine, and even the most enthusiastic soul theorist will concede that machines are not immortal.'”