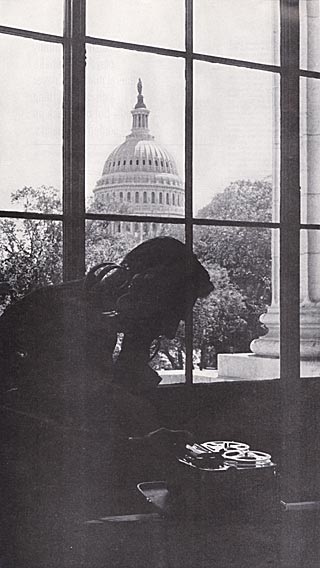

Tech-driven spying didn’t start in America recently–or even with Watergate–but the tools have grown exponentially cheaper and better over time. It has reached critical mass and won’t be completely tamed no matter the law. That doesn’t mean it’s right, just that it’s reality. The opening of “Big Brother Is Listening,” Ben H. Bagdikian’s 1964 Saturday Evening Post article:

“One evening last year, after most of the offices of the State Department Building were closed, two hard-working men let themselves into Room 3333 and began dismantling the telephone. They were Clarence J. Schneider, a technician, and Elmer Dewey Hill, a State Department electronics expert. Working under orders of John F. Reilly, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Security, the men changed some wires, reassembled the telephone and left. For two days the innocent-looking telephone in the office of Otto F. Otepka, Deputy Director of the Office of Security, doubled as a microphone, relaying everything which was said in the office, whether or not the phone was on the cradle. In a laboratory some distance away, diligent eavesdroppers recorded 12 separate conversations.

On July 9, four months later, Hill was put under oath by the Senate Internal Security subcommittee and asked, ‘Do you know of any single instance in which the [State] Department has ever listened in on the telephone of an employee?’ Hill answered, ‘I cannot recall such an instance.’

On August 6, Reilly was put under oath and asked, ‘Have you ever engaged in or ordered the bugging or tapping or otherwise compromising telephones or private conversations in the office of an employee of the State Department?’ Reilly’s answer was, ‘No, sir.’

The parties in this particular charade were engaged in some political in-fighting. Otepka, a security officer brought into the State Department in 1953, had risen to one of the top security evaluation jobs in Washington. But now he himself was under suspicion. His superiors believed that he was feeding classified information to a hostile Senate committee in order to embarrass his boss, Reilly. So Reilly had Otepka’s phone fixed to catch him in the act. He also had Otepka’s wastebaskets intercepted on the way to the incinerator and combed for incriminating material. Reilly says he lost interest in the phone tap after finding in the wastebasket a piece of carbon paper with the impression of 15 questions which Otepka had allegedly typed out for Senate investigators to ask Reilly.

At the time, these two men – Otepka and Reilly – were responsible for passing judgment on the loyalty, security and reliability of American diplomats. Hill and Reilly later ‘amplified’ their denials of eavesdropping by giving the facts and promptly resigned from the State Department. Otepka, charged with passing privileged documents without authority, carries on in a sort of limbo, marking time on the payroll while awaiting a hearing on his dismissal.

The story of Otto Otepka is part of the brave new world of white-collar eavesdropping in the United States Government. The eavesdropping may consist merely of a silent secretary’s taking down your words while you speak to her boss, or it may be a hidden microphone recording everything you say in what you think is a confidential interview. Some governmental eavesdropping is directed against espionage and crime, of course, but a great deal more is done for bureaucratic convenience and gamesmanship, either to spring a trap on a colleague or to avoid one.

These days, consequently, if you telephone a Washington official of more than middling importance – or it he calls you – the odds are disturbingly high that a third person is listening in. They are almost as high that every important word you utter is being taken down in shorthand. And while lower, the odds are still significant that your entire conversation is being taped.

In fact, Americans are so busy snooping on one another that it has almost been forgotten that Big Brother may not be an American at all. A European diplomat recently told of having discovered a man tinkering with the wall clock in his Foreign Office chamber at home; he immediately called his security men for fear the man was planting a microphone ‘for our Russian friends.’ A short time later, an American who works for the American military in Washington made an unexpected Saturday visit to his office and found a stranger in the process of dismantling his phone. The stranger had tools draped around his waist and said he was a telephone man checking phones. The American said later that he assumed a microphone was being planted. Asked who he thought responsible, he said, ‘Oh, I suppose one of our spooks’ – meaning a rival American military agency. Did it occur to him, as it had to the European, that the man could have been ‘one of our Russian friends’? The American thought about that for a moment. ‘Well, of course, it could have been,’ he admitted, ‘but I’m told our spooks do it so often, I just naturally assumed it was one of ours.”‘

Electronic snooping is not confined to Government, of course. Thanks to modern science, privacy is becoming more and more rare all over the world. Even a child can send away for a $15 device that picks up sounds in a room across the street. For $17.95 you can buy a machine that secretly tapes telephone conversations without touching a wire. And $150 buys a TV camera the size of a book that can spy on a room secretly while you watch on a distant monitor. Using these and other modern methods, American business has turned increasingly to espionage in recent years.”

Tags: Ben H. Bagdikian