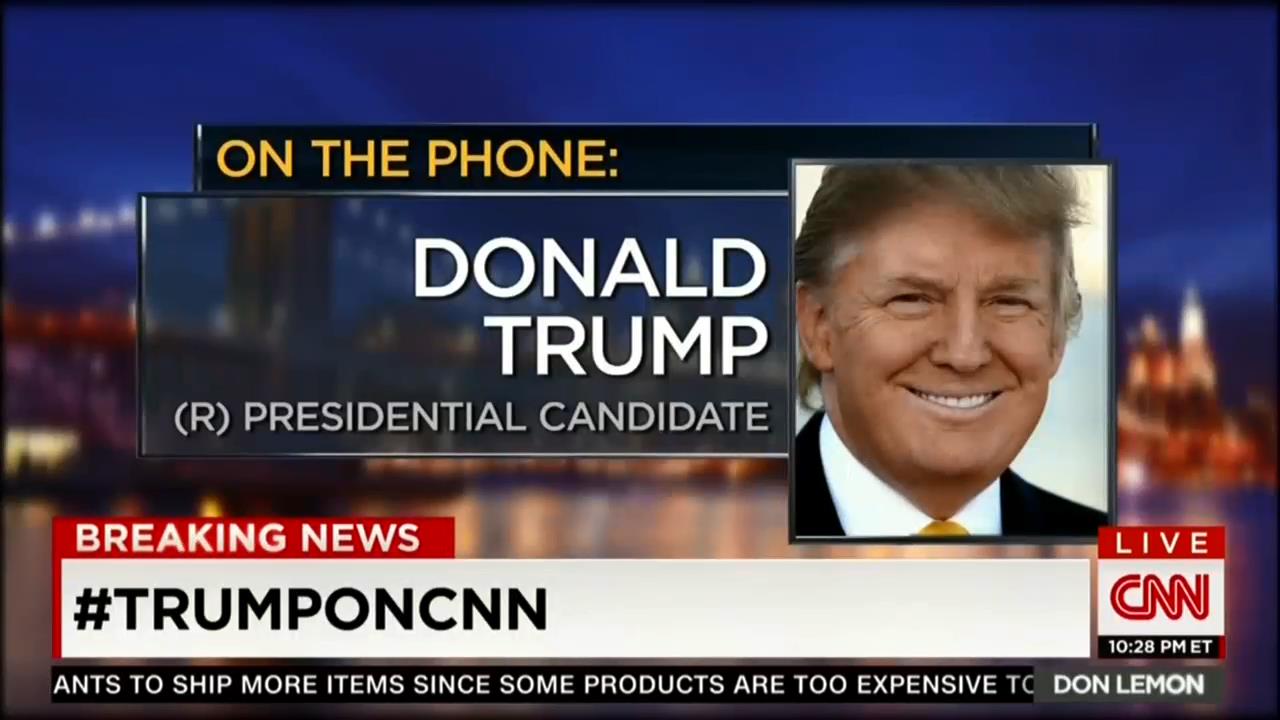

An ‘extremely credible source’ has called my office and told me that @BarackObama‘s birth certificate is a fraud.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 6, 2012

The problem with anarchy is that it has a tendency to get out of control.

In 2013, Eric Schmidt, the most perplexing of Googlers, wrote (along with Jared Cohen) the truest thing about our newly connected age: “The Internet is the largest experiment involving anarchy in history.”

Yes, indeed.

California was once a wild, untamed plot of land, and when people initially flooded the zone, it was exciting if harsh. But then, soon enough: the crowds, the pollution, the Adam Sandler films. The Golden State became civilized with laws and regulations and taxes, which was a trade-off but one that established order and security. The Web has been commodified but never been truly domesticated, so while the rules don’t apply it still contains all the smog and noise of the developed world. Like Los Angeles without the traffic lights.

Our new abnormal has played out for both better and worse. The fan triumphed over the professional, a mixed development that, yes, spread greater democracy on a surface level, but also left truth attenuated. Into this unfiltered, post-fact, indecent swamp slithered the troll, that witless, cowardly insult comic.

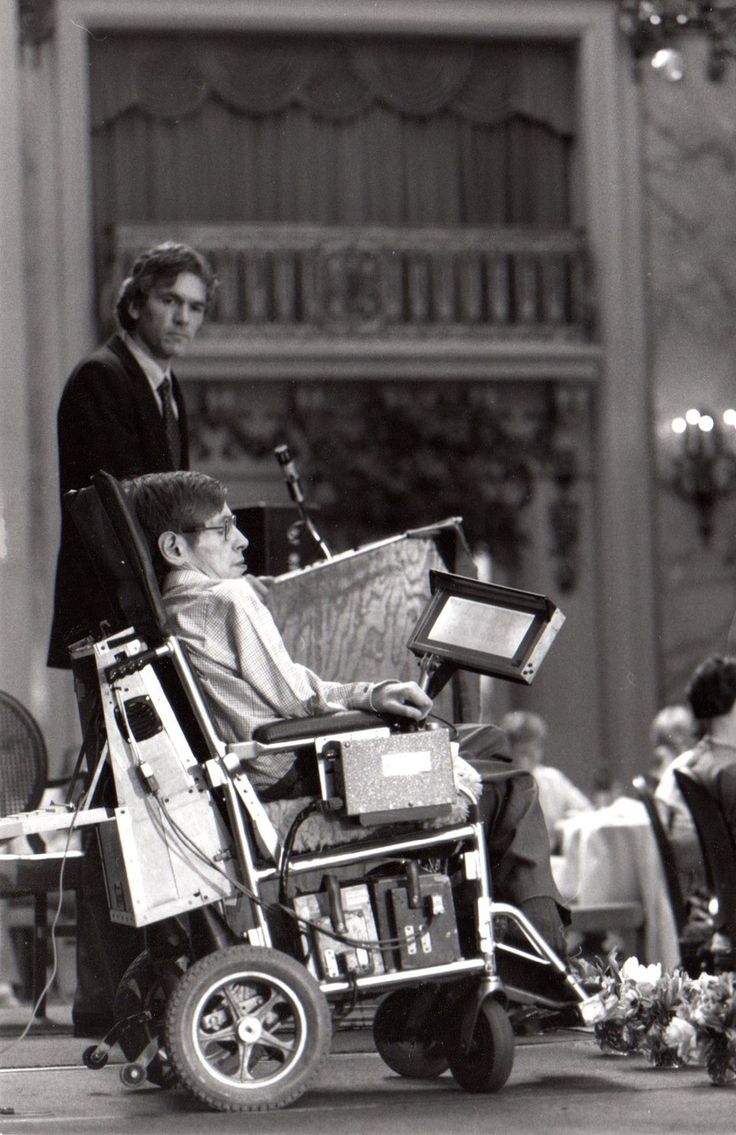

The biggest troll of them all, Donald Trump, the racist opportunist who stalked our first African-American President demanding his birth certificate, is succeeding Obama in the Oval Office, which is terrible for the country if perfectly logical for the age. His Lampanelli-Mussolini campaign also emboldened all manner of KKK 2.0, manosphere and alt-right detritus in their own trolling, as they used social media to spread a discombobulating disinformation meant to confuse and distract so hate could take root and grow. No water needed; bile would do.

In the wonderfully written essay “Schadenfreude with Bite,” Richard Seymour analyzes the discomfiting age of the troll. An excerpt:

The controlled cruelty of the wind-up didn’t need trolls to invent it. In the pre-internet era, it perhaps seemed more innocent: Candid Camera; Jeremy Beadle duping a hapless member of the public. The ungovernable rage of the unwitting victim is always funny to someone, and invariably there is sadistic detachment in the amusement. The trolls’ innovation has been to add a delight in nonsense and detritus: calculated illogicality, deliberate misspellings, an ironic recycling of cultural nostalgia, sedimented layers of opaque references and in-jokes. Trolling, as Phillips puts it, is the ‘latrinalia’ of popular culture: the writing on the toilet wall.

Trolls are also distinguished from their predecessors by seeming not to recognise any limits. Ridicule is an anti-social force: it tends to make people clam up and stop talking. So there is a point at which, if conversation and community are to continue, the joke has to stop, and the victim be let in on the laughter. Trolls, though, form a community precisely around the extension of their transgressive sadism beyond the limits of their offline personas. That the community consists almost entirely of people with no identifying characteristics – ‘anons’ – is part of the point. It is as if the laughter of the individual troll were secondary; the primary goal is to sustain the pleasure of the anonymous collective.

*

For most organised trolls, having an explicit political affiliation or moral cause goes against the basic principle that commitment to anything other than the lulz is suspect. However, for ‘gendertrolls’, a term coined by Karla Mantilla, the objective is clamorously counter-feminist. It is to silence publicly vocal women by swarm-like harassment, misogynistic insults (such epithets as ‘cunt’ and ‘whore’), ‘doxxing’ (exposing the details of someone’s offline life), and threats of rape and murder. As Mantilla sees it, there is nothing unique about this behaviour: it isn’t ‘about the internet’, but a continuation of the ‘long history of men harassing and denigrating women as a means of trying to drive out potential competitors’. It is a ‘mass cultural response to women asserting themselves [in] previously male-dominated areas’.

The new inflection that the internet appears to make possible is the trolls’ disavowal of moral commitment, which depends on a strict demarcation between the ‘real’ offline self, and online anonymity. I am not what I do, as long as I do it online.•