The end is always near, depending on how you keep time. In 1925, a Long Island house painter-cum-preacher Robert Reidt convinced himself–and many others–that the four horsemen of the apocalypse were galloping with intent. A fireball was to strike New York City and Mars would provide refuge for only the souls that were saved, it was promised. The mania that ensued, which included casualties, was recalled four years later in an article in the October 8, 1929 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, published just days before a real disaster occurred–the financial crash that led to the Great Depression. A postscript: Despite Reidt’s seeming newfound humility on display in this report, he decided again in 1932 that the Earth was soon to be a goner. Thankfully, he was mistaken once more. The article:

“Baldwin, L.I.–The crack of doom–or just the end of the world in every-day language–was formally predicted for the night of February 6, 1925.

Even if it didn’t come true, don’t you remember?

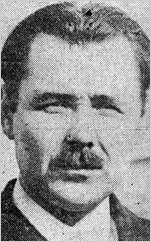

“Reidt neither looks nor talks like one would expect of a forecaster of such dire disaster.”

The little groups of serious and intent men and women–‘brides of the lamb’–who stayed up and shivered all that mid-winter night in tumble-down shacks in Patchogue and Valley Stream, L.I., awaiting the bolt of flames, the cloud of smoke, and the outpouring of floods that were to blast all earthly life. Stripped of their possessions for the end, and watching intently the slowly moving hands of the clock that didn’t strike the appointed doom.

Dawn and disillusionment. Shattered faith, and existences to be picked up all over again.

Modern Paul Revere.

And the grim, determined, exhorting young leader of the Long Island believers, Robert Reidt, the Prophet of Doom. And his rides for weeks over snow and ice in his battered model T Ford as the modern Paul Revere of a crashing and crumpling sphere.

In the three and a half years since he sent shivers up many backs and the world failed him by rolling merrily on, Reidt has become convinced that he is a better house painter than prophet.

So, a bit taciturn and something of a recluse, he is sticking to his painting and papering in and about this fast growing community, forgetful of doom and refusing to commit himself on it. He has, indeed, renounced the role of a prophet. An excellent workman, they say here, he has rebuilt his fortunes since coming through broke and virtually homeless, with a brood of four youngsters to support on the dawn when the sun surprised him by coming up.

Reidt neither looks nor talks like one would expect of a forecaster of such dire disaster. He has a broad Dutch smile, a sense of humor that has mellowed of late, and a neatly trimmed mustache. He also wears good clothes and taken on a bit of weight since he gave night and day to obtaining converts to his miscalculated crackling.

His youngsters, two boys and two girls, go to school and play with their neighbors children in Lynbrook, where they live with their mother. They don’t know doom was ever ordained.

“Mrs. Rowen disappeared from her Hollywood home for some time when the movement she had started failed to stand the test of time.”

In all, Main Street and the cities, plains and mountains, there were 140,000 ‘brides of the lamb’ keeping the vigil that, they were told, would furnish them refuge on Mars while unbelievers perished in space. They took their cues from Mrs. Margaret Rowen, Hollywood ‘prophet,’ who has since turned seeress, and Reidt dropped his paint bucket and brush around Christmas time, in 1924, to take charge of recruiting the ‘brides of the lamb’ in the metropolitan district.

The ‘Prophet of Doom’ rushed into print, and mostly on the front pages, with the impending sweep of fire, smoke and water that was to signalize the second coming of Christ, destruction of the sinful world, and the corralling of the faithful for the greater adventure. Biblical prophecies and astronomical calculations entered into the fixing of the date, positively. The exhortations went into every corner of the world.

Even though the newsprints and public generally failed to heed the th sounding note of doom seriously, the followers of Mrs. Rowen and on Long Island, of Reidt and his aide, John Downs, carpenter, enlisted the largest army the world has witnessed for th impending devastation. It was fully three times as large as the ‘Doomsday’ believers of 1848. There was, in the wake of the prophecy and waiting for the end, a fair share of tragedies.

A woman in Pennsylvania committed suicide. A 12-year-old boy ran away from home in Greenpoint and was found weeping at the altar in a Catholic Church. A disillusioned adherent hung himself on the West Side of Manhattan, and in Michigan a farmer, who had been planning a life of ease and travel on $35,000 head saved, killed himself and wounded his wife.

And, too, a few of the faithful gave up their jobs as they came to believe the prophecy, wondering what good work would do them.

The widest drawn tragedy that went with disillusionment, though, through Long Island and through the country, was the lack of material possessions most of the 140,000 had to face the world with when the ball kept spinning.

Part of the ritual for becoming a ‘bride of the lamb’ was for believers to disavow their worldly goods as the zero hour approached. Some, or perhaps most, of the followers were fortunate in that friends took just temporary care of their possessions as they prepared to await. Others had long, hard pulls in the chill of mid-winter as their rewards.

The little group at Valley Stream that sat up in the home of Mrs. Katherine B. Kennedy, with only enough coal to last them until dawn, renounced Mrs. Rowen and all prophets when dawn came up instead of doom.

The largest group that waited with Reidt and his lieutenants were more patient, for a while. They said that the end might just be delayed. Then they went, gradually, back to work and their families, Reidt moving for the time being to Newark before returning to Long Island and settling down in Baldwin.

Mrs. Rowen disappeared from her Hollywood home for some time when the movement she had started failed to stand the test of time. There was talk out there of an investigation to determine what had become of funds collected from believers and supposedly sent to her for spreading her prophecies, but nothing ever came of it, and the prophetess went in for occultism.

Reidt is through with propheting. He’s satisfied to stick to his paints.”