Bobby Fischer seemed just another American eccentric, trying to write his own ticket because the rules of the game weren’t expansive enough to contain his genius. But he was imploding from the start–deeply ill, not just a diva. Two excerpts from Bard Darrach’s troubling 1971 Life magazine portrait of Fischer in Buenos Aires, as he was on the precipice of becoming the first World Chess Federation number-one ranked player.

___________________________

In the lobby people rushed up to Fischer from all directions. He looked startled and irritated. Argentina is chess-crazy (there are 60 chess clubs in Buenos Aires alone) and for more than a month he had been stalked day and night by Latin adoration. A white-haired man collared him now and spoke earnestly. A young girl grabbed his arm and said something intense that made him pull back and then stride away. A U.S. TV sports team puffed along at his elbow, but he wasn’t having any. “Later!” he flung at them and, tilting forward, lurched off with a powerful wambling stride that made him look like Captain Ahab making headway in a high wind. Never a man to enjoy the scenery when he can look at a chessboard, Fischer works out a problem on his chess wallet as he takes a trip in a small plane.

At the London Grill, a transplanted English pub of pleasantly peeling charm, Fischer made for a back table and ordered two 12-ounce glasses of fresh orange juice, the largest steak in the house, a mixed green salad and a pint bottle of carbonated mineral water. Five minutes later he ordered another glass of orange juice, and by the time he was ready for a huge dish of bananas and superrich Chantilly cream he had finished his fourth pint of mineral water. He ate with the oral drive of a barracuda and talked incessantly about how wonderful the food was. “Look at that juice! Fresh, not frozen! And where else can you get a glass that big for less than ten cents? Look at that steak! It’s almost two inches thick. And YOU can really taste it! Not like that lousy American meat, all full of chemicals. This is natural meat! I tell you, Argentine food is the finest in the world! They really go in for quality here. Like clothes. You can get a tailor-made suit here for less than $100, and they last! Shoes too. They got the best shoes in the world here. Look at this pair I got on. Here, look at them!” Quickly untying an enormous brown shoe, he took it off and handed it across the table. “Look at that sole! It’s composition and I’m telling you it’s strong! I go through an ordinary pair of shoes in days. Days! But I’ve had this pair for a year and it’s still great. I mean I love America and I’d never be anything else but an American, but things are failing apart up there. Everybody doing his own thing just won’t work. We need organization! We need to get back to basic values!” Shaking his head sadly, he ordered another dish of bananas and Chantilly.

At sundown, as he does at sundown every Friday of his life, Fischer disappeared into his room for 24 hours of solitary meditation. He is a member of the Church of God, a fundamentalist California-based religious sect, and he takes his religion seriously. He won’t talk about it, though. He won’t talk to the press about any aspect of his private life. But a good deal is known.

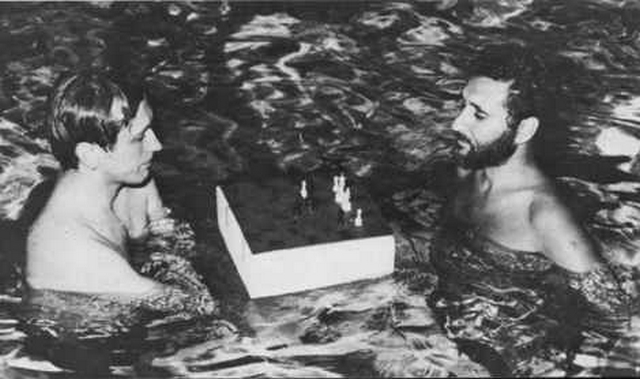

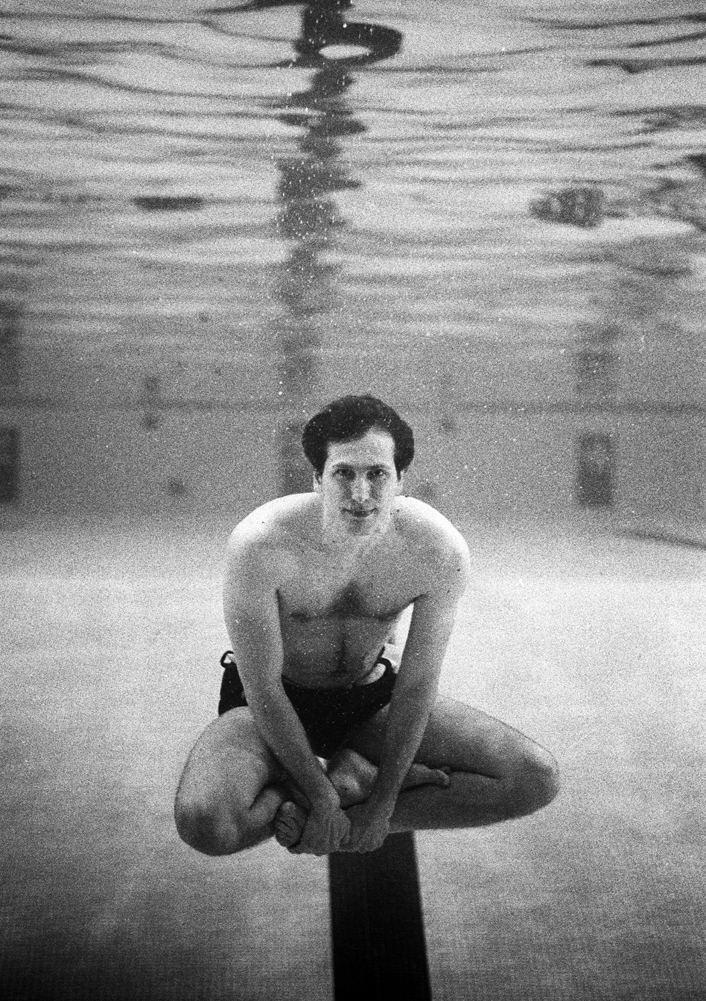

Child of a broken marriage, Bobby grew up in Brooklyn with a dominant mother and an absent father. He seemed lonely and a little withdrawn, in no way a remarkable child, until one day when he was 6 his older sister happened to bring home a chess set. From that day, bobby’s destiny possessed him. Father, mother, friends: all the people he needed he found, in a set of chess figures, all the world he wanted was there in a square foot of space. Later he tries another sport with somewhat less skill but the same furious will to win.

At 13, Bobby won the U.S junior championship. At 14, Bobby ripped through eleven matches, three with grandmasters, to become U.S. champion; the youngest ever. But his mother felt strongly that he was too little appreciated. She went to Washington and picketed in Bobby’s behalf. One day she actually chained herself to the White House gate. Acutely embarrassed, Bobby gradually pushed her out of his life. At 17, he quit school (“Teachers,” he said, “are jerks”) and lived alone in a warren of chess literature.

___________________________

At sundown on Saturday Fischer burst out of an elevator into the lobby of his hotel. An even bigger crowd was there. Dead-white with hunger after a day without food, he put his head down and headed for the street. He had promised an American TV network an interview that evening, but he pushed the cameraman aside impatiently. “Later, later!” Shutters clicked on all sides as he hit the sunlight. A husky Argentinian paparazzo gave pursuit, snapping shots every few feet. Suddenly Fischer swerved at him, grabbed for his camera but missed, then gave him two quick kicks in the right leg. Before the photographer could regain balance, Fischer turned the corner and was gone. Looking shaken, the photographer sat for some time on the fender of a nearby cab. “Bobby es loco,” he muttered, shaking his head. Fischer is a city boy born and bred, but he showed country instincts in the Argentine countryside. He tumbled about with a friendly collie named Ruby and at one point actually rescued an armadillo from her jaws.

An uncanny thing happened that night in Fischer’s room. Like a turtle he shrank into himself and gathered his world about him. First he switched on a Sony shortwave radio and fiddled till he picked up some soft rock from London. Then out came the Russian chess magazines. (Fischer seldom ventures beyond “chess Russian” but he reads and speaks Spanish fluently.) Eyes smoked with introspection, he played through 10, 15, 25 games at frenzied speed, slamming the pieces at the board like darts and muttering savage or mocking or fascinated comments under his breath. It was genius in full rage and it went on for almost an hour before he glanced up and remembered I was there.

“I shouldn’t have kicked him,” he said. “You can’t go around kicking people.”

Then his eyes smoked again and he raced through a dozen more games. This is it, I thought. This is Bobby’s life. Sleep all day. Grab some food. Hole up with a shortwave radio or a tape recorder or a TV set and play chess with himself all night. No people in his life if he can help it. Just a small circle of undemanding electronic acquaintances. A man alone in a monomania.•