Since he moved to the United States in 1973, De Laurentiis, 56, has become Hollywood’s most successful producer, turning out a string of unlikely hits that began with The Valachi Papers and went on to Serpico, Death Wish, Mandingo and Three Days of the Condor.

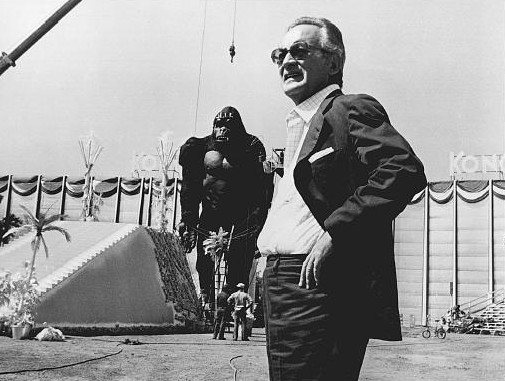

De Laurentiis recently signed, for films now in progress or soon to begin, an international all-star team of directors that includes Ingmar Bergman, Robert Altman, Martin Scorsese and Miloš Forman. They and a half-dozen less celebrated directors are working with stories on, among other subjects, Buffalo Bill, boxer Jake LaMotta, the disintegration of a marriage and—if De Laurentiis gets some legal problems solved—on a new, improved version of King Kong. The films will feature such marquee names as Liv Ullmann, Paul Newman and Margaux Hemingway, not to mention a mechanical gorilla.

How has he corralled such an array of talent, in the process earning a reputation as “the Godfather of the movie business”? Actor Charles Bronson, who will star in his fourth De Laurentiis film when he finishes the current St. Ives, says, “Because Dino invests so much in material, he’s bound to have some good stories, and stars and directors are attracted by that. But when we come to the selling of a picture, that’s where Dino really shines because he has contacts all over the world. He can pick up the telephone and book pictures even before they’re made—he has such a good reputation for success.”

It is not accompanied by any such reputation for modesty, which is perhaps understandable.

“When I leave Italy it is from zero, to start a new life,” he says, apologizing that he is still “allergic” to English. “Everybody there, they want me to come right back with no money. Now, I’m no star like Redford, who has to be recognized when he walks down the street. But I spend $6 million for properties alone in the last year, and I have only one boss: the audience.”

De Laurentiis says he left Italy because production costs had risen too high, government bureaucracy was interfering too much in the film business, and he was “tired of making movies for Italian taste.” That Italian taste also seemed to be less enchanted with him than it once had been.

After World War II, De Laurentiis rapidly made himself a power in the Italian film industry, turning out financial triumphs that occasionally won over the critics, as in Federico Fellini’s La Strada. In the mid ’50s, however, De Laurentiis split with partner Carlo Ponti and decided to go international and epic at the same time. This led to a mixed bag of florid productions from War and Peace to The Bible and finally to Waterloo, which did about as much for De Laurentiis’ prestige as it had for Napoleon’s.

At his peak in the early ’60s, De Laurentiis built a mammoth, $30 million ultramodern studio just south of Rome, with heavy government financial support. He called it “Dinocittà.” When he was forced out of the studio by business rivals and it was turned into an industrial park, he began to call it “the biggest mistake of my life.” Though he has more than recovered his esteem and fortune in the U.S., De Laurentiis still scowls when Dinocittà is mentioned. He has little else to scowl about.

Even his reputation as a tough, cynical and not hyper-scrupulous man to deal with has been gentled. True, nobody seems quite sure how De Laurentiis finances his projects, using both “private investors” and intricate arrangements with studios. De Laurentiis himself says only, “Good stories are like real estate; if you have them you can always get money.”

Even discounting the fact that for film people De Laurentiis is a potential employer to be cultivated, not cut up, his personality has become the target of relative raves.

Some are restrained. An industry veteran says, “People are surprised, but he’s a gentleman…. Well, anyway, nobody walks around calling him a son of a bitch like they do with a lot of producers.”

Others are enthusiastic, such as author Peter Maas, whose best-sellers The Valachi Papers and Serpico became film hits and whose most recent book, King of the Gypsies, will also become a De Laurentiis movie. “Before I met Dino, everybody I knew in the movie business said he was a crook and told me to stay away from him,” Maas says. “But I’ve found him to be completely honest, straightforward and loyal. He has guts—he produced The Valachi Papers after one studio executive had told my agent he wouldn’t buy the book because he didn’t want to worry that his car was going to blow up when he started it in the morning. And he has a tremendous, little boy enthusiasm for what he’s doing. Nothing turns him on like seeing a long line outside a theater showing one of his movies.”•