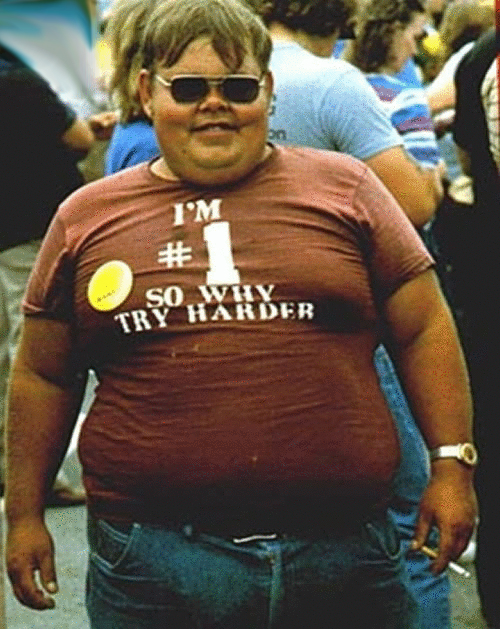

As long as people smoke, it’s difficult to argue that free markets are chastened by free wills. It’s an addiction almost always begun in adolescence, yes, but plenty of smokers aren’t even trying to quit despite the horrifying health risks. So we tax cigarettes dearly and run countless scary PSAs, trying to curtail the appetite for destruction and push aside the market’s invisible hand offering us a light.

The cost, of course, goes beyond the rugged individual, transferred onto all of us whether we’re talking about lung cancer or obesity or financial bubbles. Sooner or later, we all pay.

In a NYRB piece about Phishing for Phools, a new book on the topic by economists George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller, professional noodge Cass R. Sunstein finds merit in the work, though with some reservations. One topic of note touched on briefly: the micro-marketing of politicians aided by the “manipulation of focus.” An excerpt:

Akerlof and Shiller believe that once we understand human psychology, we will be a lot less enthusiastic about free markets and a lot more worried about the harmful effects of competition. In their view, companies exploit human weaknesses not necessarily because they are malicious or venal, but because the market makes them do it. Those who fail to exploit people will lose out to those who do. In making that argument, Akerlof and Shiller object that the existing work of behavioral economists and psychologists offers a mere list of human errors, when what is required is a broader account of how and why markets produce systemic harm.

Akerlof and Shiller use the word “phish” to mean a form of angling, by which phishermen (such as banks, drug companies, real estate agents, and cigarette companies) get phools (such as investors, sick people, homeowners, and smokers) to do something that is in the phisherman’s interest, but not in the phools’. There are two kinds of phools: informational and psychological. Informational phools are victimized by factual claims that are intentionally designed to deceive them (“it’s an old house, sure, but it just needs a few easy repairs”). More interesting are psychological phools, led astray either by their emotions (“this investment could make me rich within three months!”) or by cognitive biases (“real estate prices have gone up for the last twenty years, so they’re bound to go up for the next twenty as well”).

Akerlof and Shiller are aware that skeptics will find their depiction of human beings as “phools” to be inaccurate and impossibly condescending. Their response is that people are making a lot of bad decisions, producing outcomes that no one could possibly want. In their view, phishing for phools “is the leading cause of the financial crises that lead to the deepest recessions.” A lot of people run serious health risks from overeating, tobacco, and alcohol, leading to hundreds of thousands of premature deaths annually in the United States alone. Akerlof and Shiller think that it is preposterous to believe that these deaths are a product of rational decisions.•