Just one last thing I wanted to mention about John Markoff’s Machines of Loving Grace:The Quest for Common Ground Between Humans and Robots, which I read earlier this year and enjoyed, even though I have a sharp disagreement with the book’s underlying principle.

The writer is concerned that as Artificial Intelligence and Intelligence Augmentation battle for our research dollars, we may ultimately head down a path that sees humans replaced rather than fortified. It’s noble that Markoff wants us to question the technologists of today about tomorrow’s machines, but believing we can cooly and soberly choose between these two outcomes seems farfetched to me. Humans consistently make perplexing choices, as exemplified by our glacial transition from fossil fuels when the large majority of us accept that their use could doom us.

Three points:

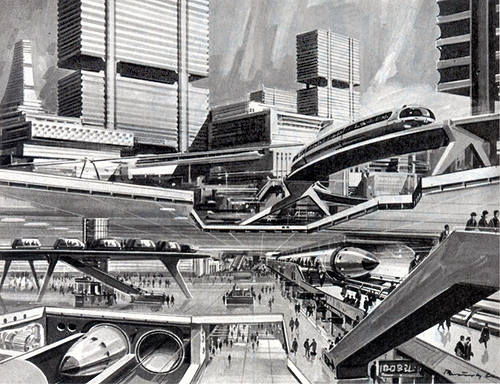

- Competition for machine dominance doesn’t occur in a vacuum, and the race for the future will occur within companies and among companies, within countries and among countries. If China or the U.S. or some other state develops an A.I. which would give it a sizable edge economically or militarily, other players would try to replicate.

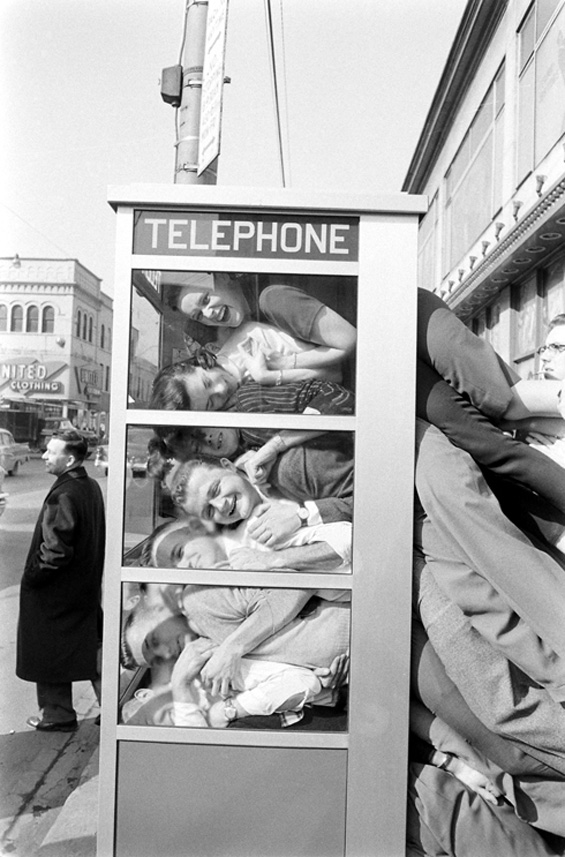

- You can’t discount the human need to discover answers, to work a puzzle to completion, even one that results in an endgame for us. In our search for greater intelligence, it’s possible we’re clever enough to finish ourselves. Humans are commanded by many non-rational forces.

- Negatives aren’t always known at the outset. When the internal-combustion engine made electric- and steam-powered vehicles obsolete, nobody thought someday a remarkably useful conveyance being powered by fossil fuels might doom humanity. We won’t always know about the next unintended consequences when working on AI and IA.

To the book’s end, Markoff maintains these decisions will be conscious ones, though a late passage asks a confounding question that (somewhat) undermines his theory. The excerpt:

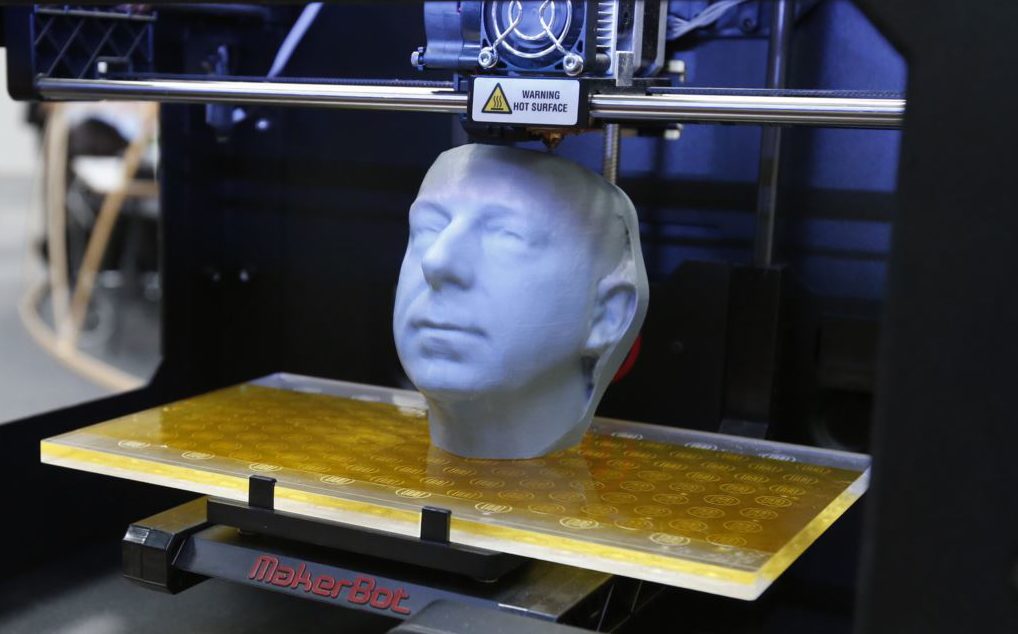

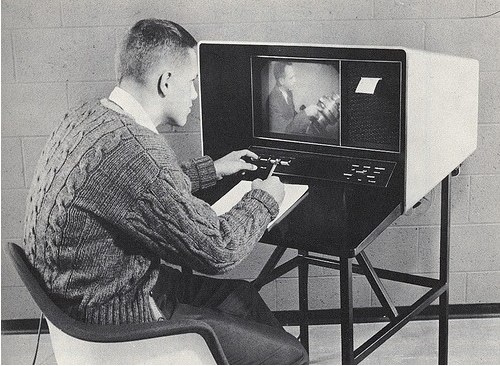

In 2013, when Google acquired DeepMind, a British artificial intelligence firm that specializes in machine learning, popular belief held that roboticists were close to building completely autonomous robots. The tiny start-up had produced a demonstration that showed its software playing video games, in some cases better than human players. Reports of the acquisition were also accompanied by the claim that Google would set up an “ethics panel” because of concerns about potential uses and abuses of the technology. Shane Legg, one of the cofounders of DeepMind, acknowledged that the technology would ultimately have dark consequences for the human race. “Eventually, I think human extinction will probably occur, and technology will likely play a part in this.” For an artificial intelligence researcher who had just reaped hundreds of millions of dollars, it was an odd position to take. If someone believes that technology will likely evolve to destroy humankind, what could motivate them to continue developing that same technology?•