The good news: You can get a lot of bang for your buck these days, really wonderful amenities you could never have afforded in the past. The bad news: It would be really helpful if you were dead. In Raymond Carver terms: Can you please be dead, please? From Greg Beato’s new Reason article, “Better Off Dead: The Cheap, Exciting Afterlife Of Modern Mortal Remains“:

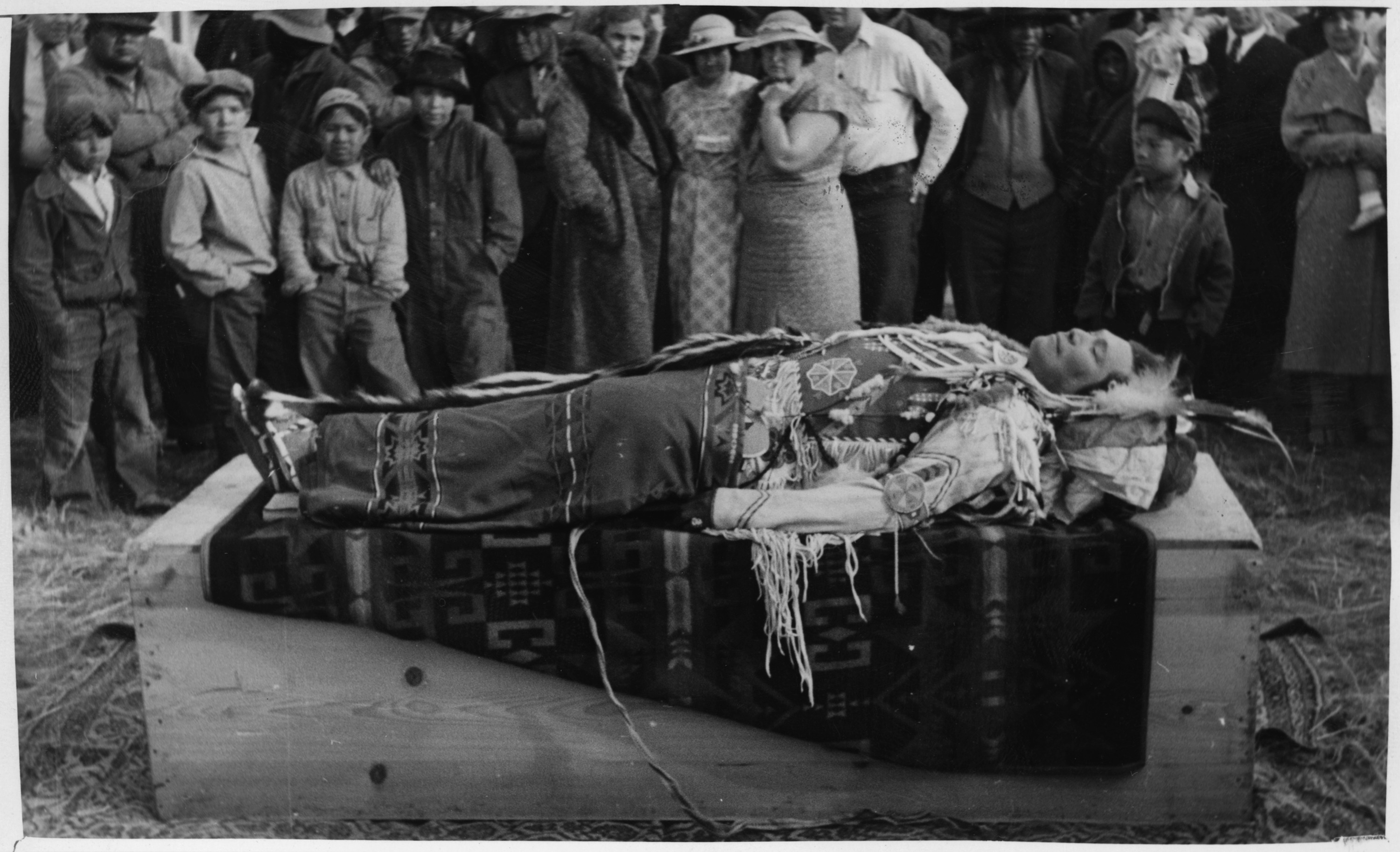

“But if the intervening 50 years have taught us anything, it’s that 1963’s corpses were woefully underserved. Sure, the ‘1 percent’ of that era could afford stunning crypts and mausoleums that were far more lavish and better appointed than the homes most of us spend our lives in. For everyone else, however, death was a homogenizing force more ruthless than any communist regime. Everyone who died got an overpriced casket, an awful post-mortem makeover, and a bland grave marker immortalizing them in the same conventionally abstract fashion as everyone else who had died that century.

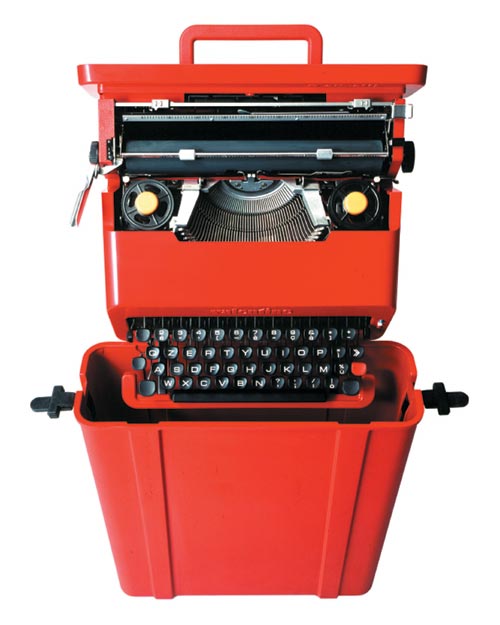

Now, we’ve got caskets that look like beer cans, headstones shaped like teddy bears, companies that will provision your loved ones with white doves to release graveside. Major League Baseball teams, many colleges, and the rock band KISS, among others, license their logos for use on caskets.

As the number of afterlife options expands, prices are dropping. For years only licensed funeral directors could sell caskets, a practice that kept prices artificially high. According to a 1988 FTC study, the average price of a casket in 1981 was $1,010, or $2,513 in 2011 dollars. In 1984, however, Congress passed the Funeral Rule, which in part requires that funeral homes accept a casket purchased from a third-party provider without charging any additional fees.” (Thanks Browser.)