Excellent article at Capital by my old pal Steven Boone, in which he does the Wi-Fi shuffle, scamming free connectivity wherever he can and summing up our somnambulant, searching age. An excerpt:

“Back home I had run into many such late-night nerd-drifters at the Apple store on 58th Street. An angry young black British writer had tipped me to the glories of 24-hour Apple joints one night, when we both found ourselves kicked out of the Grand Central Terminal wifi hotspot at closing time.

58th Street was a revelation. So this was where all the weirdoes who used to fill the early-2000’s Internet cafe on Times Square had migrated.

Under the supervision of highly tolerant Apple store Geniuses, folks could play with the latest MacBooks, iPods, Shuffles, Airs, iPhones, and iMacs (iPads were still a few months off) for as long as they could stand or lean at the waist-level display tables. Others who brought their own devices siphoned wifi while sitting on the stone bench encircling the store’s Logan’s Run-looking glass elevator.

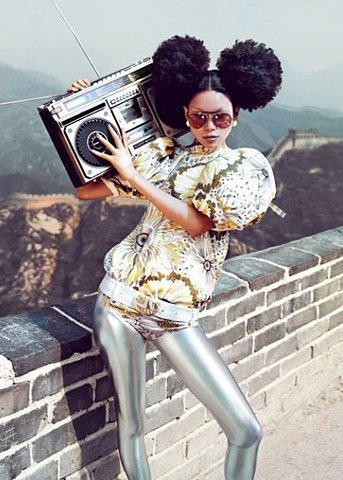

My favorite stand-up regular was a wild Hispanic man who scoured YouTube for reggaeton booty-shaking videos. None of my business, except that he would watch the clips full-screen on the store’s biggest iMac display, the speaker bass thumping while he ground his hips in the approximate space the dancing women’s butts would have occupied if the videos were holograms. Here was the only argument for 3-D that I could respect. On a similar theme, I once overheard a young, broke playboy arranging a booty call on one of the iPhones. Speaking above the store’s iTunes-diverse muzak, he told the girl he was just leaving the studio.

Others conducted important business on the phones, shouting or sobbing or plaintively whispering. Been there, too: The day my MacBook and phone got stolen, I ran to the Geniuses before I thought to run to the cops.

This was the future a lot of dystopian sci-fi authors warned us about, where a private, profit-hungry corporation could make itself feel like Mom’s house.“