Andy Greenwald has a really good article at Grantland about comedy in the time of Twitter and Instagram, inspired by Jimmy Fallon’s attempt to be crowned the new King of Late Night, but I don’t know that I agree with his conclusion about contemporary comics being “transparent.” The long tail of distribution and the decentralization of media have made for more opportunities to pursue our dreams even if most of those positions pay far less or not at all. Comics, like anyone else in media, need to place advertisements for themselves on as many channels as possible. But I don’t think that means that we get to see the real person any more now than we have in the past, except for the rare slip-up. Ubiquity is one thing but reality another. And our so-called Reality TV era has very little to do with being real. It’s still scripted, just with worse writing.

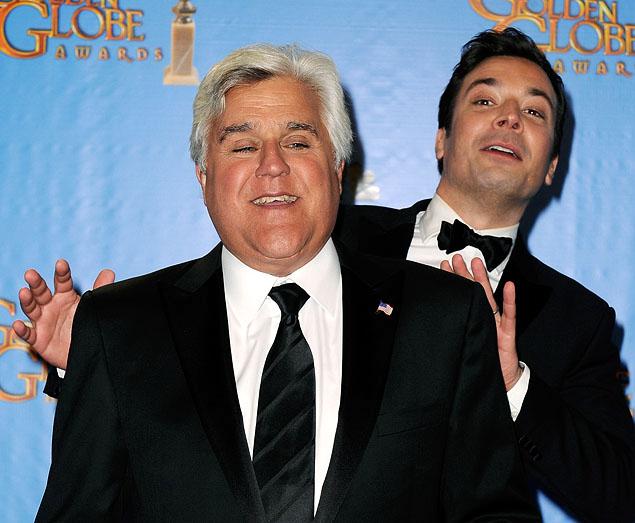

Fallon seems to be a younger and handsomer version of Jay Leno: a machine-like dispenser of entertainment who reveals very little of his real self except for the aspects he wants to stress in order to connect with his audience. If anything, he’s smoother, not as rough around the edges, having knocked about less, never having been homeless and arrested for vagrancy the way Leno was when he was trying to make his way in the L.A. stand-up scene. That’s not an insult to Fallon. There’s nothing wrong with him creating an image for himself, but it never feels particularly revelatory on a personal level. We may see Fallon and his peers in the media constantly now, but constancy doesn’t necessarily reduce distance, and being more connected doesn’t really mean we’re any closer. From Greenwald:

“When Tina Fey was a guest on Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee, she was friendly but reticent, wondering aloud how she’d continue to ‘stay opaque.’ But these days, transparency is a requirement for a young comedian. Audiences don’t want to be told jokes, they want to be in on them. Flubs and falls are endearing; seeing the cracks is what cracks people up. Jimmy Fallon has proven himself to be the ideal comedian for this moment because he understands that being funny is now a full-time gig, that oversharing is just another way of being generous. Forget leaving them wanting more: Fallon can’t ever leave them at all. He always has to be on, and so too does his show, tweeting out gags, offering up videos, and, with the help of the incomparable Roots, making Studio 6A feel like a madcap launching pad for creativity and joy, not just a destination for A-listers with projects to push. From across a generational divide and, for now at least, several tax brackets, Jerry Seinfeld and Jimmy Fallon seem to have reached the same conclusion at exactly the right moment. Comedy has a new mantra and it’s working like gangbusters: Always let them see you sweat.”