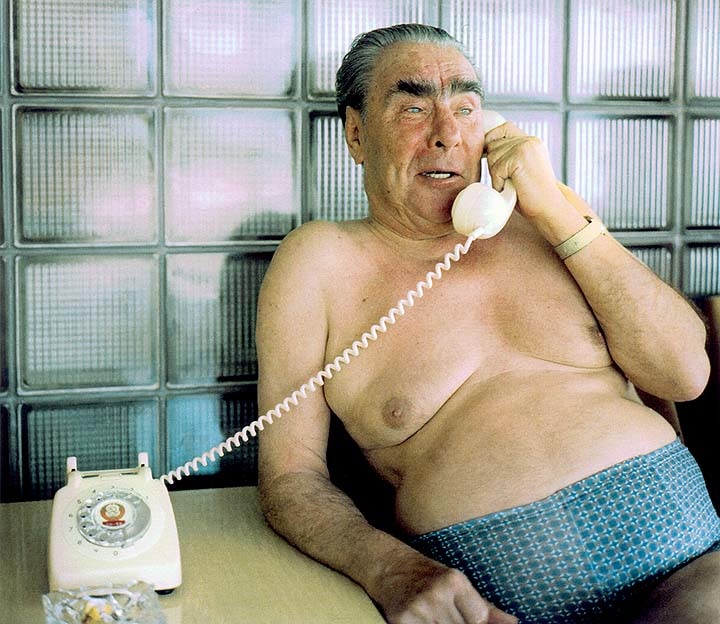

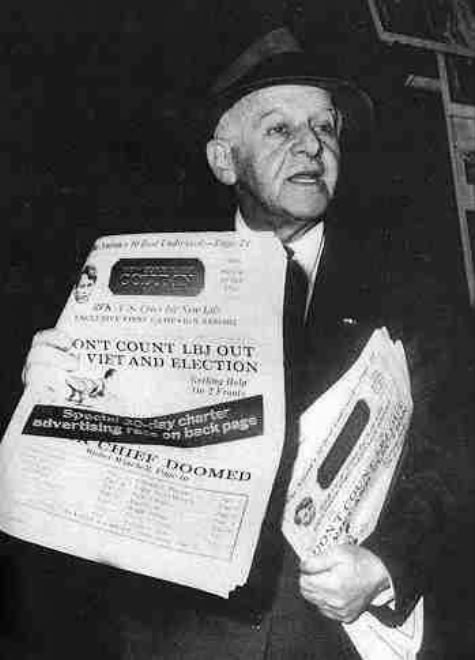

In all the kaleidoscopic years from bootleg liquor to the hydrogen bomb, few figures have been more consistently or controversially both creator and chronicler of news than a fifty-nine-year-old former song-and-dance man named Walter Winchell. Winchell, whose schooling terminated in the sixth grade, has seen his contributions to the language (infanticipating, Chicagorilla) duly noted by H. L. Mencken and included in freshman English textbooks. As the originator of the modem gossip column, he upended journalistic technique. His syndicated commentaries built him a huge national audience, later multiplied by his staccato Sunday-night (215 words a minute) newscasts. This fall he has added another dimension to a phenomenal career as the star of his own TV variety show over NBC.

Winchell’s waking hours, once merely frantic, now approach final chaos. His nightly prowlings about Manhattan are punctuated by the conversational delivery of an animated typewriter. Shortly after seven one recent evening, he strode briskly up Broadway (“the Sappian Way”) to Lindy’s Restaurant, fortified himself against the hours ahead with a chocolate soda, poetically signed a little girl’s menu (“Bread is food / Water is drink / An autograph is just some ink”), described to early dinner arrivals a five-alarm fire (“Oh, did you miss the action!”), acknowledged (“Hello”) the greeting of a former member of Murder, Inc., and an hour later abruptly left with a dozen people yet vying for his ear.

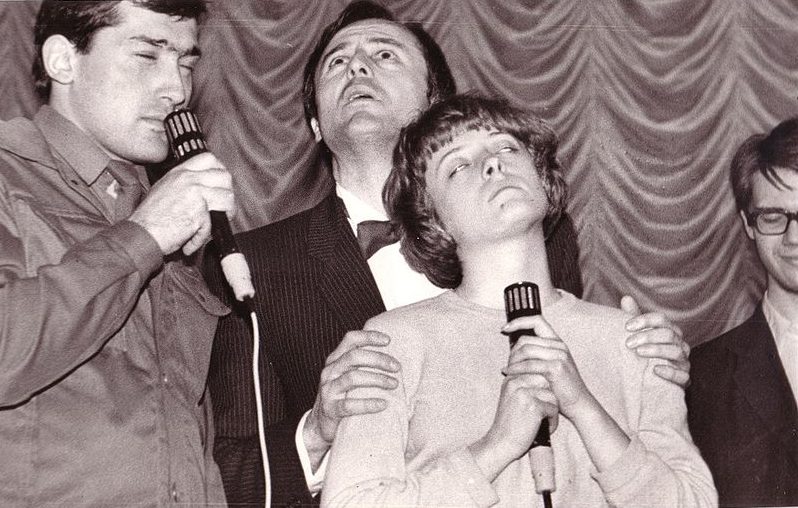

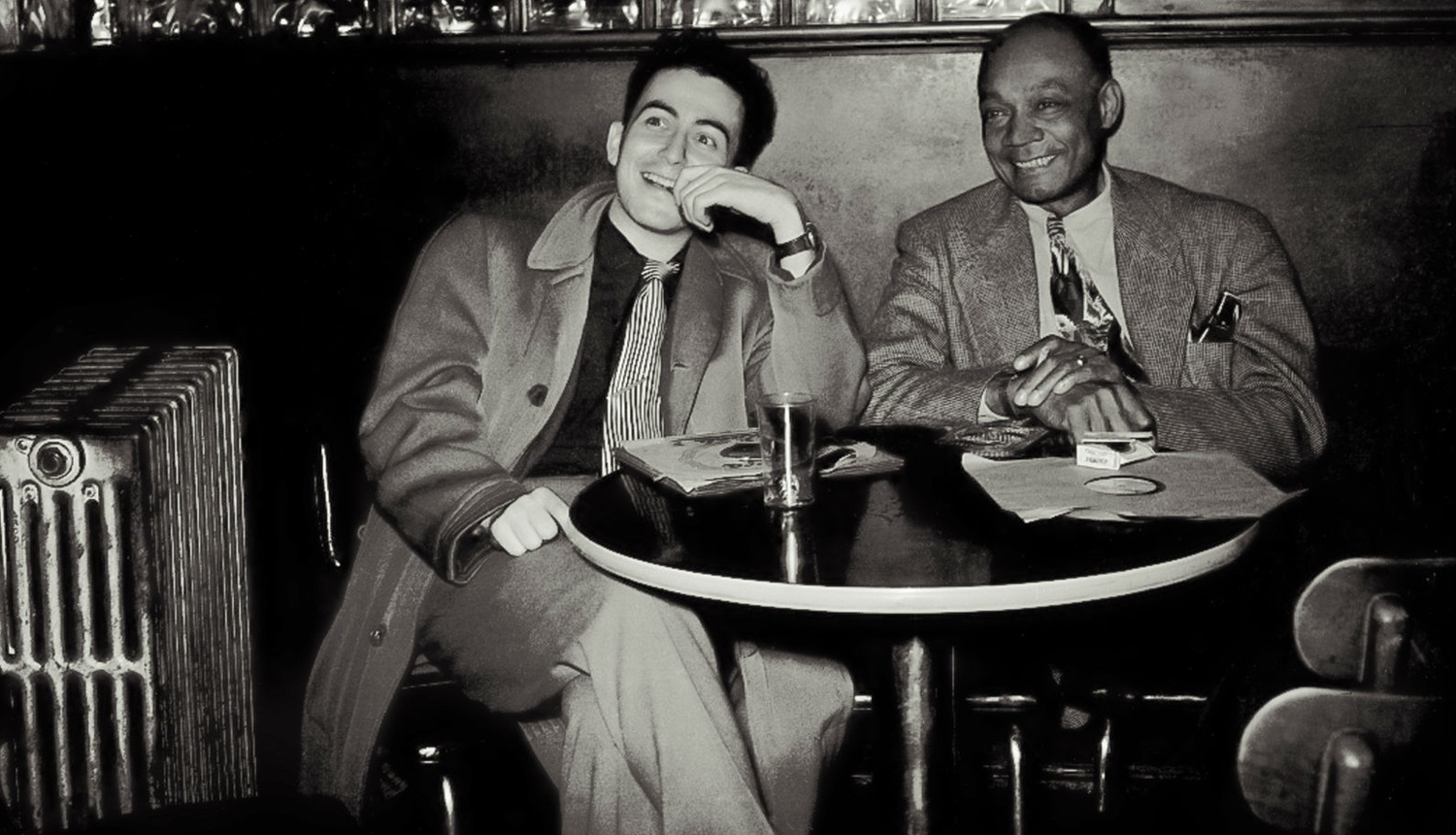

Backstage at a nearby theater, he asked Sammy Davis, Jr., to appear on his TV show, commented on his recent split with Stork Club owner Sherman Billingsley (“I think I’ll open Winchell’s Bar and Grill across the street”), dropped into a Broadway music shop as he regularly does to listen to both sides of a Roberta Sherwood record (“She doesn’t want to open an engagement without me”), paused outside to talk to an elderly lady (“1 know you, you’re Mrs. America!”) and then said, as he invariably does at some point in the night, “Let’s go chase the burglars.”

Thus, at ten o’clock, he rolled forth in his car (complete with short-wave receiver) to answer all police and fire calls within striking distance. Along with the mambo, this is his principal mode of relaxation. Most police officers know him by sight now and, if not, his standard introduction, “My name’s Winchell; I’m a reporter,” usually suffices.

At a Signal 30 (crime of violence) this night he arrived simultaneously with the police and pistol in hand (“What am I doing this for? I’m fiftynine years old”) gave chase to a hoodlum—who eventually escaped. Soon thereafter, he attended a political reception where he lectured Tammany bigwig Carmine De Sapio on the shortcomings of the Truman administration. He then left to go to a night club, El Morocco, hastily munched a steak sandwich, whirled through several mambos with Elizabeth Taylor (when she said it was her first dance in five years, he told her, “That’s why marriages break up” ) and invited Deborah Kerr and a 20th Century-Fox executive to ride in the car. Upon depositing Miss Kerr at her hotel at 4:00 A.M., he invited her to appear on his TV show. When 20th Century demurred on the grounds of conflicting films, he later noted, “Now I’ll have to give raves to her next three pictures, good or bad. Because they’ll be saying, watch him pan us.”

Winchell resumed the chase of further police calls until, at dawn, he found himself present at an emergency birth in a tenement house. It was the first he had ever seen and he was moved to report it as a society item: “A bundle of Boy (her 2d) for Mrs. Arcario Otero of W. 22d St. Happy Baby!”

Afterward, he stopped for a cup of cafeteria hot chocolate (“It gives me energy”) and returned to his St. Morilz Hotel duplex apartment. He went directly to his offlce on the second floor, equipped with a bed, an ancient table-model typewriter and heavy beige curtains, ever drawn against the sun. There, he began his next day’s column. He finished the column at 9:0 0 A.M. Then he fell asleep.

WINCHELL APPLIES HIMSELF with equal vehemence to the fate of a Broadway play or the state of the nation. Following a recent newscast, he pointed to a soapbox orator on the street and cracked, “I’m just like him. I’m a rabble rouser too. But I’ve got syndication and a mike.”

He sees himself first as a reporter. His critics insist that he is irresponsible, and refer to him as “Little Boy Peep.” When he hears such charges. he usually reacts with the disdain of a man who has just heard the cry, “Break up the Yankees!” Although Winchell’s temper flares easily and he is continually on edge, rival columnists, except Ed Sullivan, leave him relatively unruffled and he says of them, “They print it; / make it public.”

He has no leg men as such but a number of contacts supply material they know is of specific interest to him. Otherwise, he collects his items in person or culls them from his immense daily mail. His column is currently carried by 165 papers with an audience estimated at 25,000,000. When the editors of a news weekly asked Winchell how he arrived at this figure, he told them, “I read it in your magazine.”

Winchell first got the idea for his column when, still a vaudevillian. he produced a gossipy mimeographed sheet about backstage goings on and pinned it to bulletin boards under the heading, “Daily Newsense.” Several years later on the New York Evening Graphic (a tabloid which on a dull day would have a reporter shoot up the editor’s office, call the cops and headline: “Gangland Tries to Intimidate Graphic”), he included a series of his tips, turned down by the city desk, in his regular drama column. By morning, he was the talk of the town. In 1929, Winchell was hired by Hearst’s New York Daily Mirror and immediately syndicated. The first of his regular Sunday-night newscasts began in 1932. They continue today over Mutual and are still preceded by tremendous personal tension. Winchell constantly, although futilely, admonishes himself: “Calm down!”

He is acutely conscious of his power. He is also privy to the enormous draw of gossip and often uses it as a lure to advance his own highly opinionated views on affairs of state and the world. In the 19.30s he shelved his previous disinterest in politics to, as he says, “help a man named F.D.R. win.” Soon after, he plunged with equal force into the international arena “because of two guys named Hitler and Mussolini.” Winchell currently regards himself in the forefront of the fight against Communism and, after a break in diplomatic relations with President Truman, is again a favored White House visitor. Politically, he regards himself as an Independent. “There aren’t any liberals left,” he says. “If there are, I’m one.” Scoffers deny this and charge Winchell is in over his head. They single out his violent defense of Senator Joseph McCarthy as a case in point. He angrily answers, “Who else was fighting the Commies? Name me one!”

Winchell’s volatile nature demands outlets. His cops-and-robbers exploits serve this end as well as giving him some notable scoops. His first such coup took place in 1932 when nightclub hostess Texas Guinan tipped him off that Vincent Coll, the then infamous Mad Dog Killer, was about to get his from rival mobsters. Winchell printed the item forthwith. Per prediction, Coll was mowed down some five hours later.

His most sensational exploit unfolded in 1939 after he had become a friend of FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover. Louis (Lepke) Buchalter, gangland’s high executioner, had been hunted for two years. He was America’s most wanted criminal and carried a $50,000 tag dead or alive. After a decision to surrender to the FBI, Buchalter’s problem was to get to Hoover alive. Winchell was chosen as go-between. For 20 frustrating days during August, he carried on blind negotiations that apparently led nowhere. Finally, Hoover taunted Winchell to his face (“Here he is, the biggest hotair artist in town”). But the next Sunday night on a deserted Fifth Avenue, Winchell was able to make a memorable introduction: “Mr. Hoover, Mr. Buchalter; Mr. Buchalter, Mr. Hoover.” As it turned out, Winchell lost his scoop; when he breathlessly telephoned his city desk he was brushed off with, “So what, Hitler’s just invaded Danzig.”

Winchell is a man of intense personal loyalties. His association with police and firemen during his nocturnal prowling led him to discover the inadequate death benefits provided their dependents. He promptly crusaded for the Bravest and Finest Fund to provide financial assistance (“The check gets there before the undertaker”). His closest friend was the late Damon Runyon, who rode with him nightly. Just before Runyon died from cancer of the throat, he told Winchell he hoped that one friend would remember him “once a year.” Four nights later, on Winchell’s newscast, he announced the Damon Runyon Cancer Fund. “I didn’t know what we’d get,” Winchell recalls. “Maybe fifty thousand, seventy-five tops.” To date, largely through his efforts, $11,500,000 has been raised, with no deducted expenses.

His feuds are equally violent. Although he once championed the Stork Club, he has soured on owner Sherman Billingsley (“I built the place up and III tear it down”). Winchell and Ed Sullivan are long-time foes. The bitterness was renewed when Sullivan publicly announced that Winchell was a “dead duck” after he lost his TV and radio newscasts with the American Broadcasting Company. One of Winchell’s prize possessions is an early letter from Sullivan expressing the hope he could return a Winchell favor with “something equally nice.” “I put it with all my other thank-you notes,” Winchell snaps, “in the ingrate file.”

Of show business, Winchell says, “I never left it.” He is almost universally regarded in the trade as a man whose nod of approbation will lift a hitherto obscure entertainer to stardom. Winchell’s willingness to do battle for a favored cause has produced some spectacular results. Several years ago, he took a unanimous critical flop, Hellzapoppin, under his wing and it wound up one of the eight musicals in Broadway history to run more than 1,000 performances. More recently, he has been plugging forty-three-year-old singer Roberta Sherwood, lifting her from $50 to $5,000 a week in six months.•