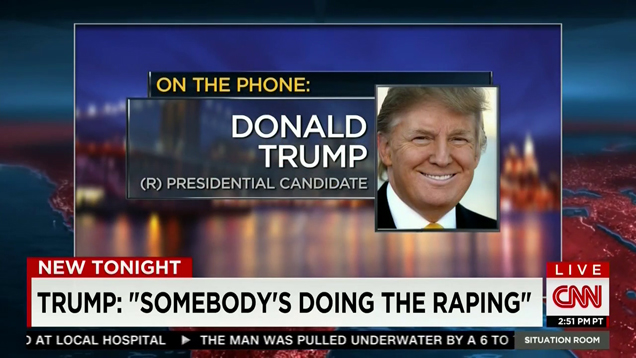

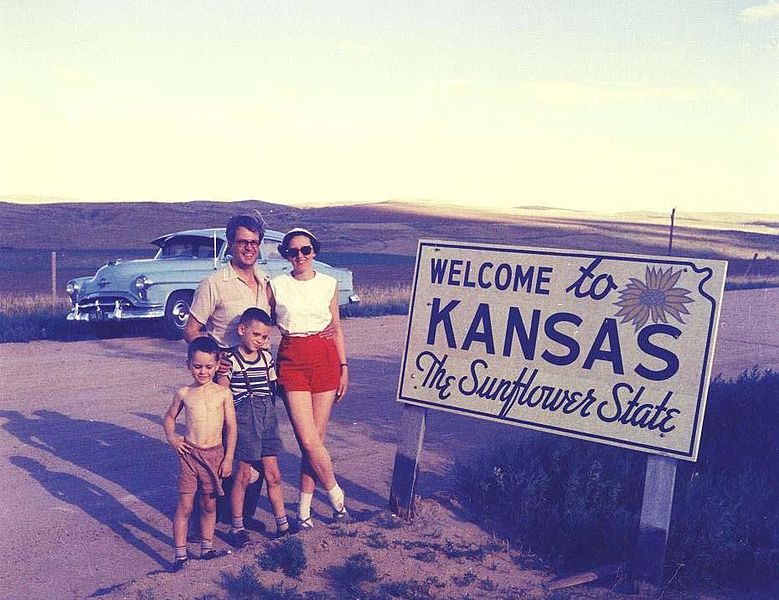

While I agree with Thomas Frank that few things are more out of touch than New York Times editorials–remember Maureen Dowd’s awful, cackling Donald Trump interview?–I can’t support his contention in the Guardian that the average Trump supporter isn’t chiefly and deeply racist. The first thing you hear from his voters isn’t that the fascist condo salesman is strong on trade but rather that “he isn’t politically correct.” Or that “he speaks the truth.” Those lines seem a dog whistle for bigotry considering the statements he’s made. His nativist blame game is the exploitation of not only economic fears but also of racial ones. Mostly the latter, I believe. Maybe the trouble with Kansas is, at long last, Kansans.

From Frank:

Stories marveling at the stupidity of Trump voters are published nearly every day. Articles that accuse Trump’s followers of being bigots have appeared by the hundreds, if not the thousands. Conservatives have written them; liberals have written them; impartial professionals have written them. The headline of a recent Huffington Post column announced, bluntly, that “Trump Won Super Tuesday Because America is Racist.” A New York Times reporter proved that Trump’s followers were bigots by coordinating a map of Trump support with a map of racist Google searches. Everyone knows it: Trump’s followers’ passions are nothing more than the ignorant blurtings of the white American id, driven to madness by the presence of a black man in the White House. The Trump movement is a one-note phenomenon, a vast surge of race-hate. Its partisans are not only incomprehensible, they are not really worth comprehending.

* * *

Or so we’re told. Last week, I decided to watch several hours of Trump speeches for myself. I saw the man ramble and boast and threaten and even seem to gloat when protesters were ejected from the arenas in which he spoke. I was disgusted by these things, as I have been disgusted by Trump for 20 years. But I also noticed something surprising. In each of the speeches I watched, Trump spent a good part of his time talking about an entirely legitimate issue, one that could even be called leftwing.Yes, Donald Trump talked about trade. In fact, to judge by how much time he spent talking about it, trade may be his single biggest concern – not white supremacy. Not even his plan to build a wall along the Mexican border, the issue that first won him political fame. He did it again during the debate on 3 March: asked about his political excommunication by Mitt Romney, he chose to pivot and talk about … trade.•