Much of American space exploration is being handed over to private enterprise, which I have some qualms about, but even some of the more prosaic elements of our lives have been offloaded from the public sector to technological “innovators.” Certainly that’s not one-hundred percent the case in the U.S., with healthcare, a huge concern, headed in the opposite direction, and the budget, while having grown slower under Obama than under Dubya or Reagan, still formidable. In a new Guardian piece, Evgeny Morozov, that self-designated mourner, looks at the dark side of capitalism and technocracy’s impact on democracy. The opening:

“For seven years, we’ve been held hostage to two kinds of disruption. One courtesy of Wall Street; the other from Silicon Valley. They make for an excellent good cop/bad cop routine: the former preaches scarcity and austerity while the other celebrates abundance and innovation. They might appear distinct, but each feeds off the other.

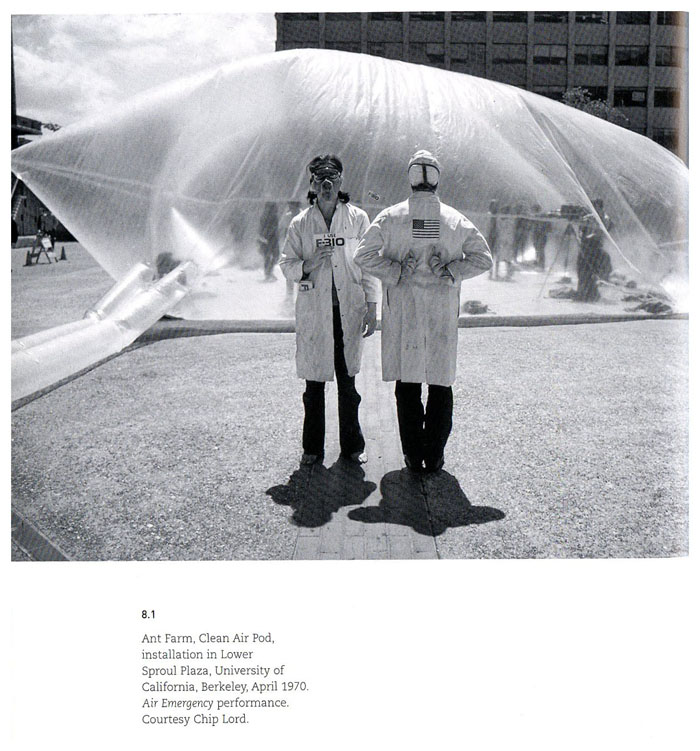

On the one hand, the global financial crisis – and the ensuing push to bail out the banks – desiccated whatever was left of the welfare state. This has mutilated – occasionally to the point of liquidation – the public sector, the only remaining buffer against the encroachment of the neoliberal ideology, with its unrelenting efforts to create markets out of everything.

The few public services to survive the cuts have either become prohibitively expensive or have been forced to experiment with new and occasionally populist survival mechanisms. The ascent of crowdfunding whereby, instead of relying on lavish and unconditional government funding, cultural institutions were forced to raise money directly from citizens is a case in point: in the absence of other alternatives, the choice has been between market populism – the crowd knows best! – or extinction.

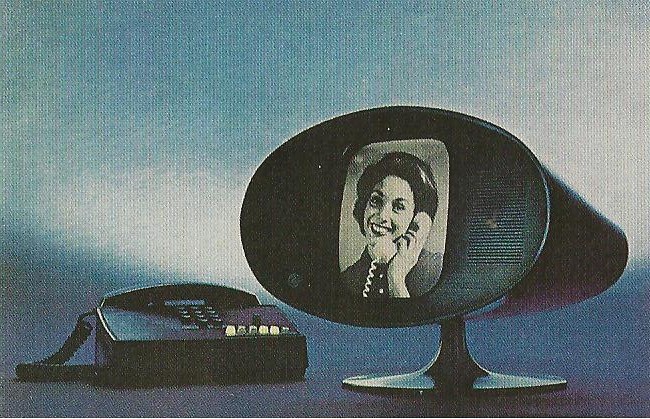

By contrast, the second kind of disruption has been hailed as a mostly positive development. Everything is simply getting digitised and connected – a most natural phenomenon, if venture capitalists are to be believed – and institutions could either innovate or die. Having wired up the world, Silicon Valley assured us that the magic of technology would naturally pervade every corner of our lives. On this logic, to oppose technological innovation is tantamount to defaulting on the ideals of the Enlightenment: Larry Page and Mark Zuckerberg are simply the new Diderot and Voltaire – reborn as nerdy entrepreneurs.

And then, a rather strange thing happened: somehow we have come to believe that the second kind of disruption had nothing to do with the first.”