I would just as soon watch work by Errol Morris as by any living filmmaker. His big-screen documentaries and episodes of his former Bravo show First Person are as perceptive about human psychology as a piece of art can be. I’ve learned so much from Morris and his Interrotron about how we piece together a reality, a consciousness, in an effort to navigate a scary world, and how often deception of self is at its core. Years ago, I interviewed him, and he had a slow, plodding manner, a tortoise who could win the race despite appearances. Two excerpts from Alex Pappademas’ insightful new Grantland Q&A with the documentarian: one about the empathy he feels for his subjects no matter how objectionable they are and the other about how this ability to understand others causes him criticism.

______________________________

Grantland:

Adams was a convicted murderer when you met him. You seem to be drawn to the type of person other people hate. It’s as if there’s something about the psychology of widely despised people that fascinates you.

Errol Morris:

Absolutely. I’ve never heard anyone put it quite that way, but it’s absolutely true. I like pariahs. There are endless examples of them. Randall Adams was a cold-blooded cop killer, labeled a psychopath. Fred Leuchter in Mr. Death — an electric-chair repairman who coincidentally happens to be a Holocaust denier.

Grantland:

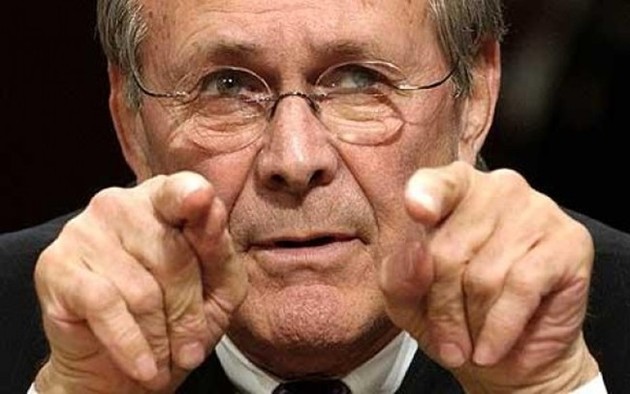

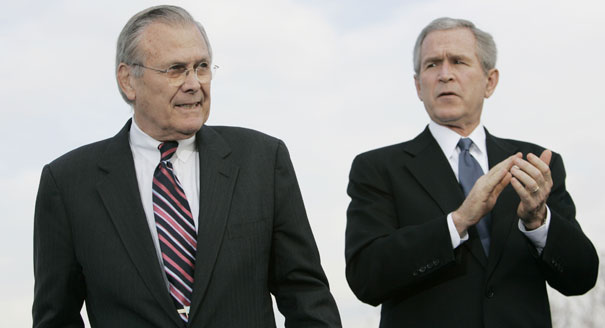

And then Robert McNamara and Donald Rumsfeld.

Errol Morris:

McNamara, Rumsfeld, probably Joyce McKinney.

Grantland:

Who’s maybe not as widely and famously despised …

Errol Morris:

Not famously despised, but adjourned, discredited, acquainted with grief. A woman of sorrows. So, yeah. I do like that. I can’t deny it.

Grantland:

Do you have to like the person, as well? In most cases, I get the impression that you do — that it isn’t hard for you to get to a place of comfort with these subjects.

Errol Morris:

No. When I was interviewing killers years ago, I enjoyed talking to them. I enjoyed being with them. I wasn’t there to moralize with them or temporize with them, I was there to talk to them. And I think that’s still true. Rumsfeld pushed it, I have to say.

Grantland:

Just your capacity for …

Errol Morris:

Empathy. Yeah.

______________________________

Grantland:

It’s interesting, though, because while you’ve generally fared pretty well with critics over the years, whenever Fog of War or The Unknown Known were negatively reviewed, it was always for that reason. Especially Rumsfeld — you got a lot of flak for somehow letting him get away. People seemed disappointed that you didn’t grab him by the lapels and shake him, rhetorically speaking.

Errol Morris:

I think there’s a whole group of people who would’ve loved for me to get out of my chair and to hit him with a cinder block, which I was not going to do. Y’know, it’s really interesting, because they made that whole movie — a horrendous movie, I think — about the Nixon-Frost interviews, and of course they changed it to make it more dramatic and more confrontational. But I think — and I could be just making excuses for myself — that there’s a portrait that emerges [in The Unknown Known] that’s very different and far more interesting than the portrait you would’ve gotten by having him walk off the set or repeatedly refuse to answer questions, which is what would’ve happened. There’s something about his manner that reveals to me much about the man. A refusal to engage stuff with any meaning is really frightening, and I think that’s part of who he is. There’s a whole class of people who love to push people around but don’t love to think about stuff carefully. Maybe it’s a different talent.•