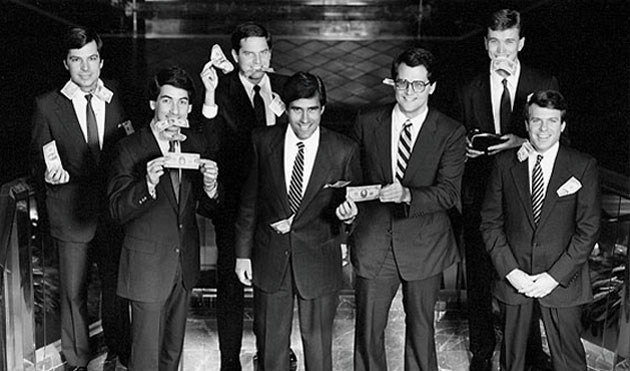

In “Dickheads,” an excellent Baffler essay, David Graeber measures the sociological and historical significance of the necktie, which he believes to be a phallus (how it’s shaped, where it points) full of cultural meaning about power. An excerpt:

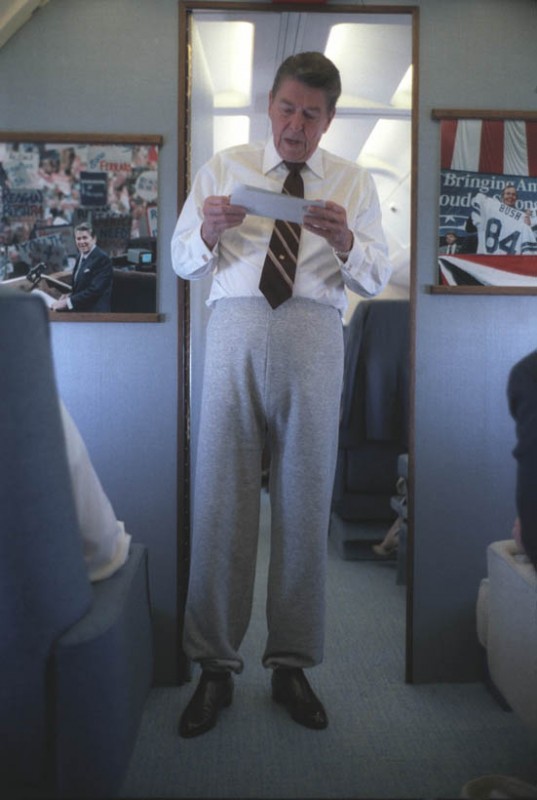

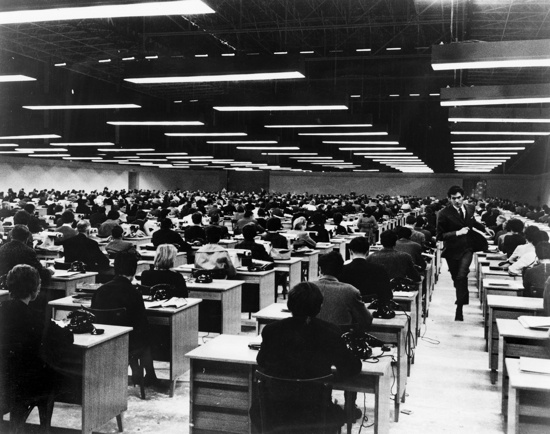

So what does any of this have to do with neckties? Well, at first glance, the paradox has only deepened. If the message of the suit is that its wearer is a largely invisible, abstract, and generic creature to be defined by his ability to act, then the decorative necktie makes little sense.

But let’s examine other forms of decoration allowed in formal attire and see if a larger pattern of sartorial power begins to emerge. Decoration that’s specific to women (earrings, lipstick, eyeshadow, etc.) tends to highlight the receptive organs. Permissible men’s jewelry—rings, cuff links, fancy watches—tends to accentuate the hands. This is, of course, consistent: it is through the hands that one acts upon the world. There’s also the tie clip, but that’s not really a problem. The tie and the cuff links seem to fulfill their functions in parallel, each adding a little decoration to tighten a spot where human flesh sticks out, namely the neck and wrists. They also help seal off the exposed bits from the remainder of the body, which remains effaced, its contours largely invisible.

This observation, I think, points the way to the resolution of our paradox. After all, the male body in a suit does contain a third potentially obtrusive element that is most definitely not exposed, something that, in fact, is not indicated in any way, even though one does have to take it out, periodically, to pee. Suits have to be tailored to allow for urination, which also has to be done in such a way that nobody notices. The fly (which is invisible) is a bourgeois innovation, much unlike earlier aristocratic styles, such as the European codpiece, that often drew explicit attention to the genital region. This is the one part of the male body whose contours are entirelyeffaced. If hiding something is a way of declaring it a form of power, then hiding the male genitals is a way of declaring masculinity itself a form of power. It’s not just that the tie sits on precisely the spot that, in women’s formal wear, tends to be the most sexualized (the cleavage). A tie resembles a penis in shape, and points directly at it. Couldn’t we say that a tie is really a symbolic displacement of the penis, only an intellectualized penis, dangling not from one’s crotch but from one’s head, chosen from among an almost infinite variety of other ties by an act of mental will?

Hey, this would explain a lot…•