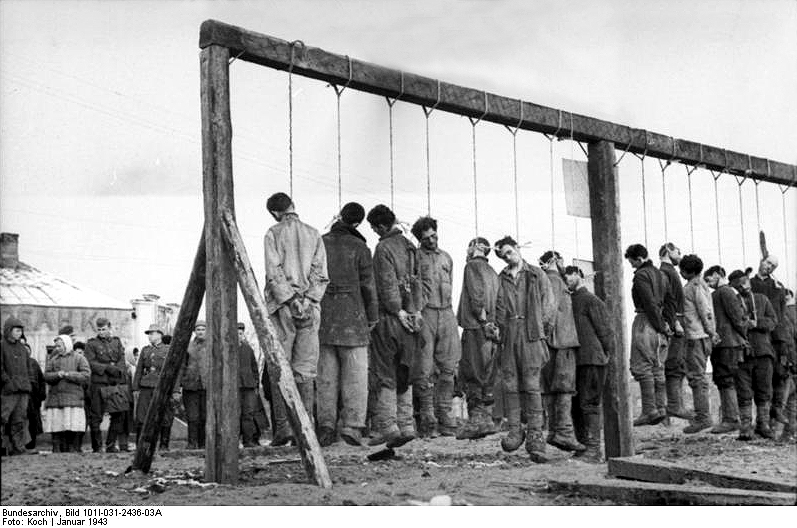

As far as domestic atrocities in America can be measured, I would think that the conduct at Fort Sumter, the Civil War military prison in Georgia, ranks with anything after slavery and the treatment of Native Americans. The open-air stockade prison (nicknamed Andersonville by inmates) held 45,000 prisoners during its 14-month existence, with nearly a third succumbing to starvation, lack of drinking water and disease. Swiss-born Confederate officer Henry Wirz commanded the camp and was known for his brutality and severity. Even though the lack of supplies and pen-type jail weren’t his fault alone, Wirz was the one executed for the crimes against humanity. The classic photograph above shows him as he’s about to have his sentence carried out. From the story of his hanging in the November 10, 1865 New York Times:

“WIRZ was executed this morning at 10:30 o’clock. Nobody who saw him die to-day will think any the less of him. He disappointed all those who expected to see him quiver at the brink of death. He met his fate, not with bravado, or defiance, but with a quiet, cheerful indifference. Smiles even played upon his countenance until the black coat shut out from his eyes the sunlight and the world forever. His physical misery, whatever it may have been, was completely hidden in his last and successful effort to die bravely and without any exhibition of trepidation or fear, so his step was steady, his demeanor calm, his tongue silent, except as he offered up his last prayer, and all his bearing evinced more of the man than at any time since his first incarceration. The crowd said he was a braver man than PAYNE, or HERROLD, or ATZEROTH. Perhaps it was the bravery of a desperate man, who knows mercy is beyond his hope. Nevertheless, he met his fate with unblanched eye, unmoving feature, and a calm, deliberate prayer for all those whom he has deemed his persecutors. He seemed to have convinced himself of his own innocence, and his last principal conversation was full of protestations that he died unjustly, and that others were just as guilty as he.

Yesterday afternoon, LOUIS SCHADE, WIRZ junior counsel, communicated to him the result of his last appeal to the President. WIRZ said he had no hope. He was ready to die. He had sought and received religious consolation, and it mattered little whether he died now or was spared to die a natural death, for die soon he must. An attache of the Swiss Consulate also called to ascertain the residence of his relatives, that they might be officially apprised of his death. WIRZ said he had been greatly wronged by the refusal of the Swiss Consul to receive money to enable him to conduct his defence.

WIRZ ate his supper as usual, and retiring, slept soundly the best part of the night. This morning he arose early and partook of a moderate breakfast. Soon after, R.B. WINDER, who was associated with WIRZ in the command at Andersonville, was allowed to visit him, and the two had a long conversation, devoted to a review of their career at the stockade, a review of the evidence, and mutual assertions that they were equally guilty, or rather, equally innocent, and that if WIRZ deserved hanging, so did WINDER. WINDER then bade WIRZ an emotional farewell at half-past eight o’clock. Mr. SCHADE was admitted for a farewell interview, during which the prisoner reiterated his thanks for his counsel’s efforts, and expressed himself as to his innocence, much as he had done before. It is due to Mr. SCHADE to say that he has been indefatigable in seeking to prolong the life of his client. He left the prison at the close of the interview, and went to the President’s, where at ten thirty-five he made his last appeal. WIRZ was hung at ten thirty-two.

WIRZ ate his supper as usual, and retiring, slept soundly the best part of the night. This morning he arose early and partook of a moderate breakfast. Soon after, R.B. WINDER, who was associated with WIRZ in the command at Andersonville, was allowed to visit him, and the two had a long conversation, devoted to a review of their career at the stockade, a review of the evidence, and mutual assertions that they were equally guilty, or rather, equally innocent, and that if WIRZ deserved hanging, so did WINDER. WINDER then bade WIRZ an emotional farewell at half-past eight o’clock. Mr. SCHADE was admitted for a farewell interview, during which the prisoner reiterated his thanks for his counsel’s efforts, and expressed himself as to his innocence, much as he had done before. It is due to Mr. SCHADE to say that he has been indefatigable in seeking to prolong the life of his client. He left the prison at the close of the interview, and went to the President’s, where at ten thirty-five he made his last appeal. WIRZ was hung at ten thirty-two.

After Mr. SCHADE left WIRZ, his spiritual advisers, Fathers BOYLE and WIGET entered and remained with him until he was led forth to the scaffold.

…

At thirty minutes past ten, his hands and legs having been pinioned by straps, the noose was adjusted by L.J. RICHARDSON, Military Detective, and the doomed man shook hands with the priests and officers. At exactly thirty-two minutes past ten, SYLVESTER BALLOU, another detective, at the signal of the Provost-Marshal, put his foot upon the fatal spring, the trap fell with a heavy noise, and the Andersonville jailor was dangling in the air. There were a few spasmodic convulsions of the chest, a slight movement of the extremities, and all was over. When it was known in the street that WIRZ was hung, the soldiers sent up a loud ringing cheer, just such as I have heard scores of times on the battle-field after a successful charge. The sufferings at Andersonville were too great to cause the soldiers to do otherwise than rejoice at such a death of such a man.

After hanging fourteen minutes the body was examined by Post-Surgeon FORD, and life pronounced to be extinct. It was then taken down, placed upon a stretcher, and carried to the hospital, where the surgeons took charge of it.

No sooner had the scaffold and the rope done its work, and become historically famous, than relic seekers began their work. Splinters from the scaffold were cut off like kindling wood, and a dozen feet of rope disappeared almost instantly. The interposition of the guard only saved the whole thing from being carried off in this manner.

The surgeons held a post-mortem, and an examination of the neck showed the vertebrae to be dislocated. His right arm, which has been the chief cause of his physical misery, was in a very bad condition, in consequence of an old wound having broken out afresh. His body also showed severe scrofulitic cruptions.

Agreeably to a request from WIRZ, Father BOYLE received the body to-day, and delivered it to an undertaker, who will inter it, to await the arrival of Mrs. WIRZ, who is expected soon. WIRZ left few or no earthly effects. The only things in his room after the execution were a few articles of clothing, some tobacco, a little whisky, a Testament, a copy of Cummings on the Apocalypse, and a cat, which was WIRZ’s pet companion. This is all there is left of him.”

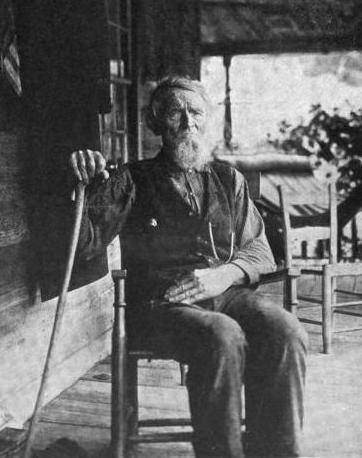

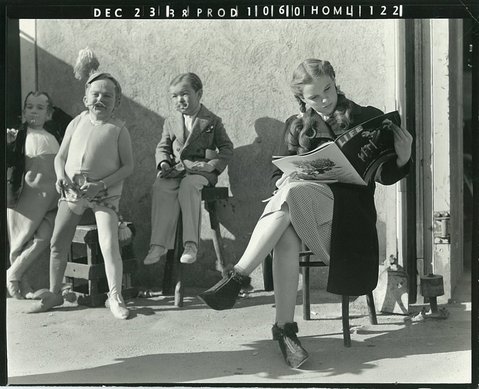

Andersonville survivor, May 1865.