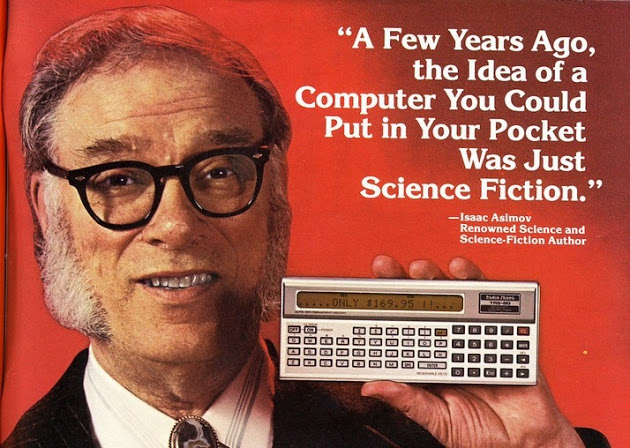

Humans experience consciousness even though we don’t have a solution to the hard problem. Will we have to crack the code before we can make truly smart machines–ones that not only do but know what they are doing–or is there a way to translate the skills of the human brain to machines without figuring out the mystery? From Marvin Minsky’s 1982 essay, “Why People Think Computers Can’t“:

“CAN MACHINES BE CREATIVE?

We naturally admire our Einsteins and Beethovens, and wonder if

computers ever could create such wondrous theories or symphonies. Most

people think that creativity requires some special, magical ‘gift’ that

simply cannot be explained. If so, then no computer could create – since

anything machines can do most people think can be explained.

To see what’s wrong with that, we must avoid one naive trap. We mustn’t

only look at works our culture views as very great, until we first get good

ideas about how ordinary people do ordinary things. We can’t expect to

guess, right off, how great composers write great symphonies. I don’t

believe that there’s much difference between ordinary thought and

highly creative thought. I don’t blame anyone for not being able to do

everything the most creative people do. I don’t blame them for not being

able to explain it, either. I do object to the idea that, just because we can’t

explain it now, then no one ever could imagine how creativity works.

We shouldn’t intimidate ourselves by our admiration of our Beethovens

and Einsteins. Instead, we ought to be annoyed by our ignorance of how

we get ideas – and not just our ‘creative’ ones. Were so accustomed to the

marvels of the unusual that we forget how little we know about the

marvels of ordinary thinking. Perhaps our superstitions about creativity

serve some other needs, such as supplying us with heroes with such

special qualities that, somehow, our deficiencies seem more excusable.

Do outstanding minds differ from ordinary minds in any special way? I

don’t believe that there is anything basically different in a genius, except

for having an unusual combination of abilities, none very special by

itself. There must be some intense concern with some subject, but that’s

common enough. There also must be great proficiency in that subject;

this, too, is not so rare; we call it craftsmanship. There has to be enough

self-confidence to stand against the scorn of peers; alone, we call that

stubbornness. And certainly, there must be common sense. As I see it, any

ordinary person who can understand an ordinary conversation has

already in his head most of what our heroes have. So, why can’t

‘ordinary, common sense’ – when better balanced and more fiercely

motivated – make anyone a genius,

So still we have to ask, why doesn’t everyone acquire such a combination?

First, of course, it sometimes just the accident of finding a novel way to

look at things. But, then, there may be certain kinds of difference-in-

degree. One is in how such people learn to manage what they learn:

beneath the surface of their mastery, creative people must have

unconscious administrative skills that knit the many things they know

together. The other difference is in why some people learn so many more

and better skills. A good composer masters many skills of phrase and

theme – but so does anyone who talks coherently.

Why do some people learn so much so well? The simplest hypothesis is

that they’ve come across some better ways to learn! Perhaps such ‘gifts’

are little more than tricks of ‘higher-order’ expertise. Just as one child

learns to re-arrange its building-blocks in clever ways, another child

might learn to play, inside its head, at rearranging how it learns!

Our cultures don’t encourage us to think much about learning. Instead

we regard it as something that just happens to us. But learning must itself

consist of sets of skills we grow ourselves; we start with only some of them

and and slowly grow the rest. Why don’t more people keep on learning

more and better learning skills? Because it’s not rewarded right away, its

payoff has a long delay. When children play with pails and sand, they’re

usually concerned with goals like filling pails with sand. But once a child

concerns itself instead with how to better learn, then that might lead to

exponential learning growth! Each better way to learn to learn would lead

to better ways to learn – and this could magnify itself into an awesome,

qualitative change. Thus, first-rank ‘creativity’ could be just the

consequence of little childhood accidents.

So why is genius so rare, if each has almost all it takes? Perhaps because

our evolution works with mindless disrespect for individuals. I’m sure no

culture could survive, where everyone finds different ways to think. If

so, how sad, for that means genes for genius would need, instead of

nurturing, a frequent weeding out.”