In “The Lives of Ronald Pinn” in the London Review of Books, Andrew O’Hagan begins with a meditation on the creepy true-life practice of undercover UK police who secretly, for four decades, assumed the identities of actual people who’d died as children or young adults, using the deceased to construct new personas for themselves in order to stealthily investigate the activities of left-wing groups. They acquired backstories and “continued” the lives. It was grave robbery as identity theft, something like fan fiction married to police work.

During the age of the Internet, such fictionalizing has even greater consequences. In what’s an admittedly very dubious ethical act, O’Hagan then creates a fake identity from the titular Mr. Pinn, a South Londoner who presumably died of a heroin overdose in 1984, discovering how easy it still is to raise the dead and breathe something like life into it, to acquire every last ungodly thing on the Dark Internet under the alias, and how much this falsification resembles much of what the average person really does in our time of avatars, usernames, purchased followers, “friends” and cryptocurrency. An excerpt:

“Stories of people pretending to be other people, of people feeling impelled to confect, imitate or perform themselves, describe a change not just in the technological basis of our lives but in the narrative strategies now available to us. You could say that every ambitious person needs a legend to deepen their own. Last year Manti Te’o, an exceptional Hawaiian linebacker, a Mormon who played for Notre Dame, found his when he told the sad story of having to succeed for his team after his 22-year-old girlfriend, Lennay Kekua, died of leukaemia. Despite his grief, the footballer stormed up the field, making 12 tackles in one game, before appearing on news programmes to talk about his heartbreak and to quote from the letters Lennay had written him during her terrible illness. Problem was: the girlfriend never existed. She was a complete invention – the photographs on social media sites were of a girl he’d never met. He’d missed Lennay’s funeral, Te’o said, because she insisted that he not miss the game. There are hundreds of stories like this, where ‘sock-puppet’ accounts on Facebook and elsewhere have allowed a ‘person’ – sometimes a whole ‘family’ – to put together a life that’s much bigger than the real one. The Dirr family from Ohio solicited sympathy and dollars for years after losing loved ones to cancer – a small village of more than seventy invented profiles shored up the lie. It was all the work of a 22-year-old medical student, Emily Dirr, who’d been inventing her world since she was 11. Her life was a reality show that she produced, cast, directed, starred in, and broadcast to the world under a pile of aliases that felt entirely real and moving to a large group of devoted followers.

By the middle of last summer, Ronnie Pinn had a Gmail account and an aol account, as well as accounts on Craigslist and Reddit. It took the best part of a week to install and run the software necessary to get the bitcoins he needed to confirm his existence. I bought them with a credit card – hundreds of pounds’ worth – on computers that couldn’t be traced back to me. In each case they had to be ‘mixed’, or laundered, before Ronnie could buy things. Around every corner on the web is a scam, and the Ronnie I invented had to negotiate with some of the dodgiest parts of the World Wide Web. He now had currency; next he got a fake address. I used an empty flat in Islington, where I would go to collect his mail, the emptiness of the hall seeming all the emptier for the pile of mail on the floor, addressed to someone who didn’t exist but was more demanding than many who did.

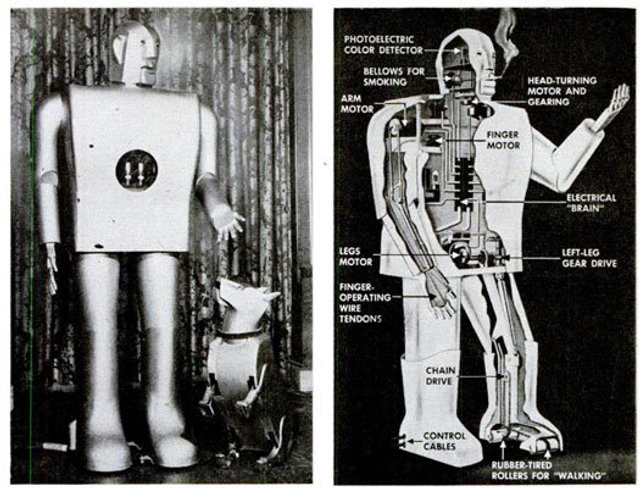

It wasn’t long before I saw Ronnie’s face on a driving licence. It took a few weeks to secure a passport. The seller was on the dark net website Evolution; having gathered all ‘Ronnie’s’ information, he produced scans on which the photographs were missing. Then he disappeared. This is common enough: the sellers no less often than those seeking to buy their wares are crooks. Another seller produced the documents quite quickly and with everything in place anyone could have been fooled. Not perhaps the e-passport gates at Heathrow, but a British passport is a gateway ID to many other forms of ID, as well as to a world of legitimacy. Slowly and digitally, ‘Ronnie’ began to be a man who had everything, a face, an address, a passport, discount cards. He began to have conversations with real people on Reddit, or people who might have been real, and his Twitter and Facebook life showed him to be a creature of enthusiasm and prejudice. Nowadays, everyone can be Frankenstein and his monster, both the hare-brained dreamer and his gothic offspring, and the enabling technology seems to encourage the idea. Ronnie, in the world, was a figment, but on discussion boards he was no less believable than anybody else. ‘Friend’ has become a verb, leaving the old world of ‘befriend’ to hint at warm handshakes and eyes that actually met. People ‘friend’ people on Facebook and they get ‘friended’, but many of them will never meet. Elsewhere on the net the connections may lead to a cold presence, a person who is legitimate but non-existent. Ronnie’s social interaction online could be involved and energetic and characterful, but it seemed that everyone he met had a self to hide and nothing to show for themselves beyond their quips and departures. At one point, Ronnie’s Twitter account got hacked and he was invaded by hundreds of robotic right-wing followers. His ‘information’ had opened him up to being exploited by spam-bots, by other machines, and by web detritus that clings to entities like Ronnie as a matter of digital course. None of these everyday spooks came in from the cold, and Ronnie moved, as if by osmosis, into the more criminal parts of the internet, where the clandestine earns its keep.”