“It started off as a kind of utopian promise,” Andrew O’Hagan writes of the Internet in a new Guardian essay that meditates on the death of privacy and, perhaps, the novel. During Web 1.0, some worried that this new-to-the-masses technology would be co-opted, watered down and lose it’s anarchic spirit, becoming a tool of corporations and governments. Never let it be tamed, they exhorted. Well, it never has been tamed and still has become a tool of corporations and governments. The anarchy is actually useful to them (see U.S. Presidential election, 2016).

The thing is, we’re still in the prelude of what the Internet will become and of what being connected will mean. Marshall McLuhan feared the Global Village, and we’re going to experience a version of it beyond what the visionary contemplated. That’s what the Internet of Things will effect, with every last object becoming a computer. It will bring great benefits while also being a machine with no OFF switch. We’ll all permanently be inside a contraption that may be antithetical to human nature. It will contain sensors but perhaps not sense.

As far as O’Hagan’s fears about the effect of social media on fiction, I addressed a similar subject in a 2015 essay about Charlie Brooker’s outstanding television program Black Mirror:

It’s tough being Paddy Chayefsky these days. Charlie Brooker, the brilliant satirist behind Black Mirror, comes closest. If he doesn’t make it all the way there, it’s not because he’s less talented than the Network visionary; it’s just that the era he’s working in is so different. I’ve read many articles about Brooker’s impressive program and pretty much all of them miss the point I believe he’s making about our brave new world of technology. That includes Jenna Wortham’s New York Times Magazine essay, which referred to Mirror as “functioning as a twisted View-Master of many different future universes where things have strayed horribly off-course.” The Channel 4 show is barely about the future. It’s mostly about the present. And it isn’t about the present in the manner of many sci-fi works, which create outlandish scenarios which can never really be in the service of telling us about what currently is. Brooker’s scenarios aren’t the exaggerations they might seem at first blush. In almost no time, our hyperconnected world delivers something far more disturbing than his narratives.

Chayefsky and Andy Warhol and Marshall McLuhan could name the future and we’d wait 25 or 50 years as their predictions slowly gestated, only becoming fully manifest at long last. None of that trio of seers even lived long enough to experience the full expression of Mad As Hell of 15 Minutes of Fame or the Global Village. Brooker will survive to see all his predictions come to pass, and it won’t require an impressive lifespan.•

O’Hagan, author of The Secret Life: Three True Stories of the Digital Age, believes that since we’ve surrendered an interior life (“everything became fake”), there really isn’t even a way to observe the present let alone predict the future, and that writers and readers alike are being wrecked by living in public. The novel is a dogged form and may find a way to persist regardless of each of us living in our own Reality TV show while being flattered by or fired upon by armies of bots. Perhaps it can serve as an antidote to such an existence? The writer himself believes that could be the ultimate outcome. Regardless, his excellent essay is one that can be meditated on in myriad ways.

An excerpt:

The other day I taped over the camera on my computer. Then I went upstairs and disabled the data collection capability on the TV. Because of several stories of mine, I’d suffered a few cyber-attacks recently, and, though a paragon of dullness, I decided to greet the future by making it harder to find me. One of the great fights of the 21st century will be the fight for privacy and self-ownership, which is also, to my mind, the struggle for literature as distinct from the dark babble of social media. Writers thrive on privacy, not on Twitter, and so do readers when the lights are low. Giving your sentences thoughtlessly away, and for nothing, seems a small death to contemplation, and does harm to the profession of writing, where you’re paid because you’re good at it. We are all entertainers now, politicians are theatrical in their every move, but even merely passable writers have something large at stake when it comes to opposing the global stupidity contest. Literature, which includes great journalism, might enhance the public sphere but it more precisely enriches the private one, and we are now at the point where privacy, the whole secret history of a people, might be the only corrective we have to the political forces embezzling our times.

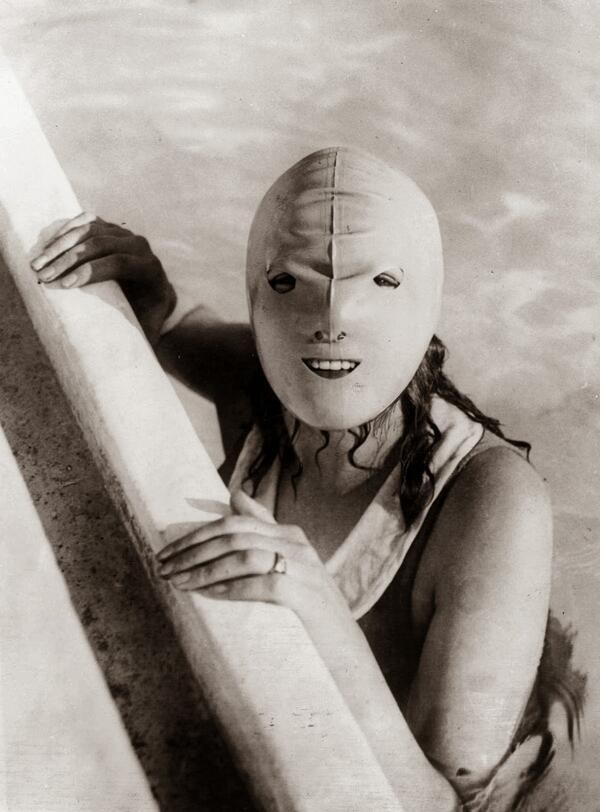

In the interests of “national security”, in the service of “global harmony”, you are now obliged to become your own Winston Smith, both watched and self-watching. The TV downstairs may not be “off” at all – it may be “fake-off”, a condition defined in a joint programme of June 2014 between the CIA and MI5 called “Weeping Angel”. (Certain models of televisions are programmed to stay on, with their cameras operative, and the “data” they collect can be harvested by agencies.) The principle, as with Britain’s Prevent campaign, is to assume that everyone with a private life might have something to hide, which means that nobody, in the future, unless they have sinister motives, should expect the luxury of privacy. Some TVs and all phones operate “as a bug, recording conversations in the room and sending them over the internet to a covert CIA server”, reported WikiLeaks as it released the “Weeping Angel” documents. Being bugged at home or stopped and searched in the street and having your “information” handed to security agencies are now understood to be security measures, and questioning it will make you an enemy of the Daily Mail’s “common sense”. One doesn’t have to be much of a freedom fighter nowadays to be branded a member of the “liberalocracy”: all you have to do is believe in free speech and freedom of movement, and stand up for basic rights of sovereignty over your own thinking. Only recently have these sanctities been taken for the demands of a potential terrorist.•