From the July 17, 1951 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

You are currently browsing the archive for the Urban Studies category.

Tags: Mrs. Ruth Craig

William James Sidis amazed the world, and then he disappointed it.

A Harvard student in 1910 at just 11 years old, he was considered the most astounding prodigy of early 20th-century America, a genius of mathematics and much more, reading at two and typing at three, who had been trained methodically and relentlessly from birth by his father, a psychiatrist and professor. It was a lot to live up to. There was a dalliance with radical politics at the end of his teens that threw him off the path to greatness, resulting in a sedition trial. In the aftermath, he quietly disappeared into an undistinguished life.

When it was learned in 1937 that Sidis was living a threadbare existence of no great import, merely a clerk, he was treated to a public accounting which was laced with no small amount of schadenfreude. He sued the New Yorker over an article by Gerald L. Manley and James Thurber (gated) which detailed his failed promise. He was paid $3,000 to settle the case by the magazine’s publishers just prior to his death in 1944.

Three portraits below from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle chart Sidis’ uncommon life.

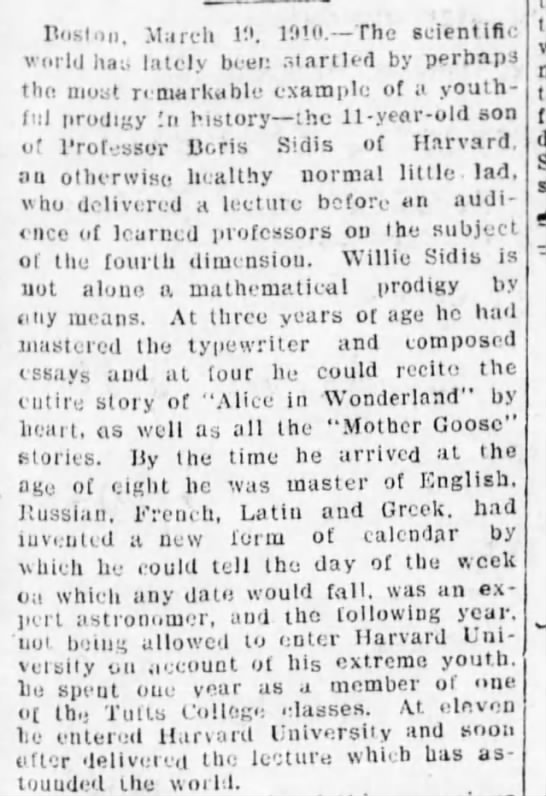

From March 20, 1910:

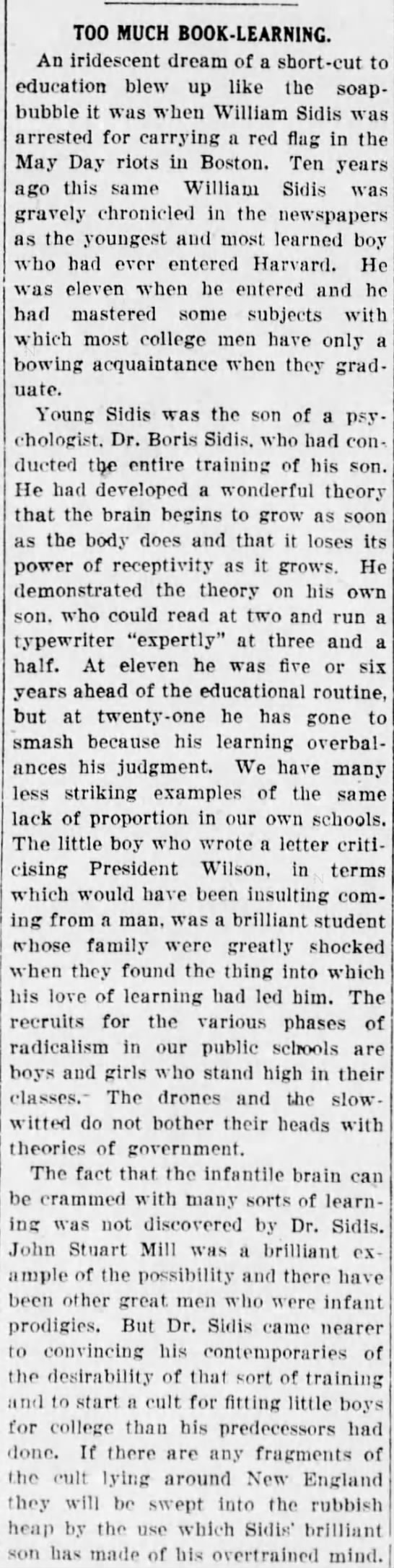

From May 5, 1919:

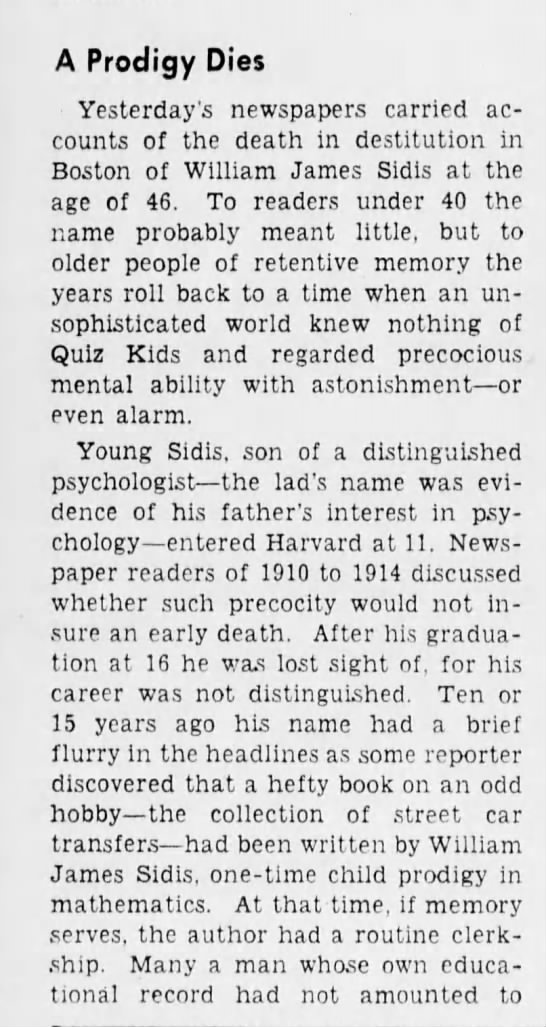

From July 18, 1944:

Not that long ago, it was considered bold–foolhardy, even–to predict the arrival of a more technological future 25 years down the road. That was the gambit the Los Angeles Times made in 1988 when it published “L.A. 2013,” a feature that imagined the next-level life of a family of four and their robots.

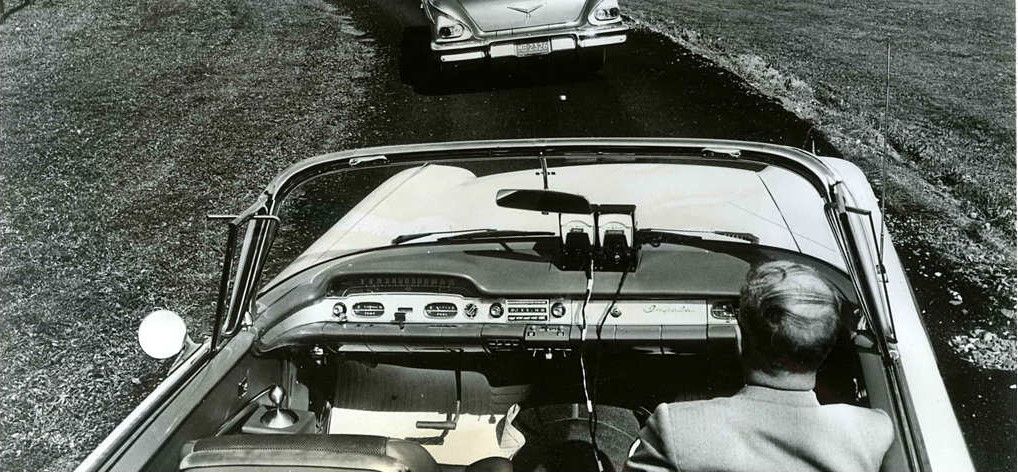

We may not yet be at the point when “whole epochs will pass, cultures rise and fall, between a telephone call and a reply“–I mean, who talks on the phone anymore?–but it doesn’t require a quarter of a century for the new to shock us now. In the spirit of our age, Alissa Walker of the Curbed LA works from the new report “Urban Mobility in the Digital Age” when imagining the city’s remade transportation system in just five years. Regardless of what Elon Musk promises, I’ll bet the over on autonomous cars arriving in a handful of years, but it will be transformative when it does materialize, and it’ll probably happen sooner than later.

The opening:

It’s 2021, and you’re making your way home from work. You jump off the Expo line (which now travels from Santa Monica to Downtown in 20 minutes flat), and your smartwatch presents you with options for the final two miles to your apartment. You could hop on Metro’s bike share, but you decide on a tiny, self-driving bus that’s waiting nearby. As you board, it calculates a custom route for you and the handful of other passengers, then drops you off at your doorstep in a matter of minutes. You walk through your building’s old parking lot—converted into a vegetable garden a few years ago—and walk inside in time to put your daughter to bed.

That’s the vision for Los Angeles painted in Urban Mobility in the Digital Age, a new report that provides a roadmap for the city’s transportation future. The report, which was shared with Curbed LA and has been posted online, addresses the city’s plan to combine self-driving vehicles (buses included) with on-demand sharing services to create a suite of smarter, more efficient transit options.But it’s not just the way that we commute that will change, according to the report. Simply being smarter about how Angelenos move from one place to another brings additional benefits: alleviating vehicular congestion, potentially eliminating traffic deaths, and tackling climate change—where transportation is now the fastest-growing contributor to greenhouse gases. And it will also impact the way the city looks, namely by reclaiming the streets and parking lots devoted to the driving and storing of cars that sit motionless 95 percent of the time.

The report is groundbreaking because it makes LA the first U.S. city to specifically address policies around self-driving cars.•

Tags: Alissa Walker

From the March 17, 1904 New York Times:

Jacksonville, Fla. — While in a cage with three lions this afternoon, Alfred J.F. Perrins, the animal trainer, suddenly became insane. Soon after he entered the cage Perrins struck one of the lions a vicious blow and cried, “Why don’t you bow to me, I am God’s agent.”

Perrins then left the cage, leaving the door open and saying, “They will come out, as God is looking after them.” He then stood on a box and called on the spectators to come and be healed, saying he could restore sight to the blind and hearing to the deaf, and heal any disease by a gift just received from God.

The lions started to leave the cage and the spectators fled. The cage door was slammed by a policeman, who arrested Perrins. Physicians announced Perrins hopelessly crazed on religion. He has been in show business thirty years, having been with Robinson, Barnum, and Sells.•

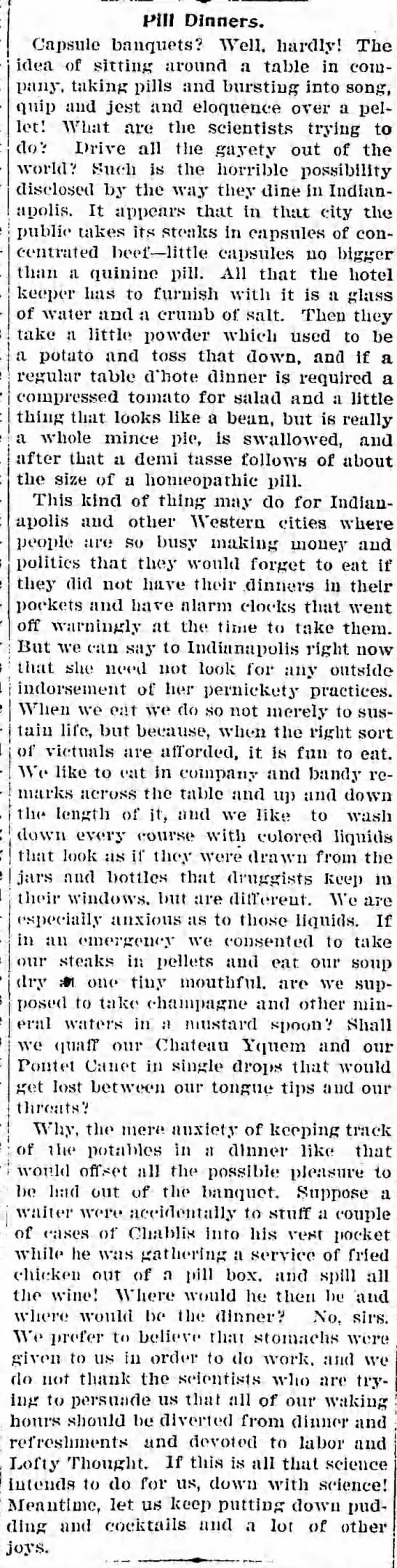

Many of the goals of the Industrial and Digital Ages have been aimed at trying to make heretofore irreducible things smaller: putting the contents of the Encyclopedia Britannica on the head of a pin, reducing musical recordings and newspapers to pure data, etc. In that same vein, scientists endeavored to shrink an entire meal to the size of a pill long before Rob Rhinehart made dinner drinkable with Soylent. An article in the August 28, 1899 Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on such efforts.

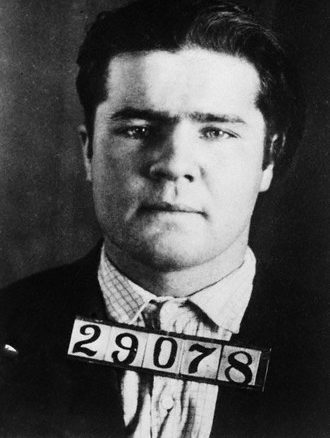

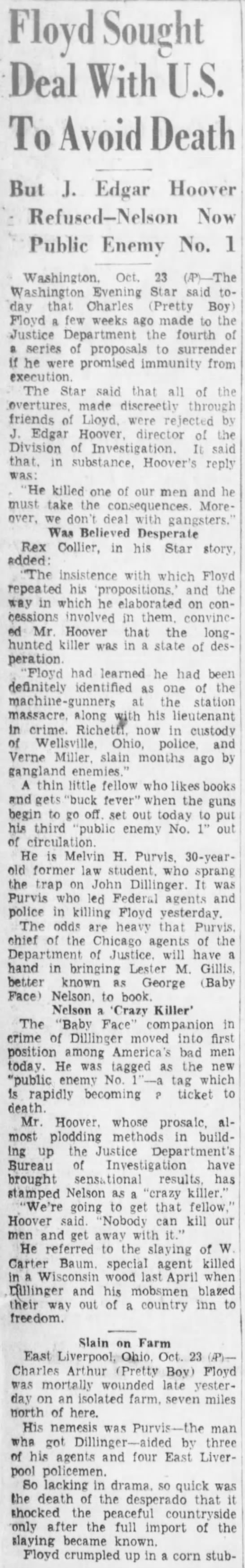

Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd was more famous than infamous, which seems a strange thing.

During the 1930s, the soft-featured felon participated in a string of brazen bank robberies and left behind a body count, but such was the hatred for financial institutions in America during the Great Depression that he was widely considered a Robin Hood if not a saint. Stories circulated that he shredded mortgages of down-and-out farmers while emptying safes and shared his ill-gotten gains with the hungry and disheartened, which was nearly everyone.

Who knows? Maybe he found time for such acts of benevolence in between shootouts and jail breaks, but these legends had more to do with what a desperate people needed than what a lone gunman was delivering. It was Woody Guthrie who put it all in perspective in his great song named after the beloved criminal, writing “Yes, as through this world I’ve wandered / I’ve seen lots of funny men / Some will rob you with a six-gun / And some with a fountain pen.”

Two Brooklyn Daily Eagle articles from 1934 recall Floyd’s wide renown at the end of his wild run.

From October 23, 1934:

From October 29, 1934:

Seminal reading about NYC of the last five decades is “My Lost City,” Luc Sante’s brilliant 2003 New York Review of Books paean to an era not too long ago when hardly anyone here was a have-not, even if they were poor, with a trove of printed matter and records and furnishings to be had on many a curb to whomever was willing to haul it away. The riches poureth over and provided a different, and often deeper, kind of wealth. Okay, some people truly had it worse four decades or so ago. For instance, child prostitutes were a staple of Times Square. Relentless gentrification, however, wasn’t the only way to deal with that horror.

Sante has now republished “The Last Time I Saw Basquiat” in the NYRB, another piece about a time of greater creativity that’s been lost, though he’s hopeful in asserting that the struggle against wealth inequality for an affordable, working-class New York continues. I wish I felt the same. In Cohen-esque terms, the war to me seems over, the good guys having lost.

An excerpt:

The last time I saw Jean I was going home from work, had just passed through the turnstile at the 57th Street BMT station. We spotted each other, he at the bottom of the stairs, me at the top. As he climbed I witnessed a little silent movie. He stopped briefly at the first landing, whipped out a marker and rapidly wrote something on the wall, then went up to the second landing, where two cops emerged from a recess and collared him. I kept going.

A month later he was famous and I never saw him again. We no longer traveled in the same circles. I was happy for him, but then it became obvious he was flaming out at an alarming pace. I heard stories of misery and excess, the compass needle flying around the dial, a crash looming. When he died I mourned, but it seemed inevitable, as well as a symptom of the times, the wretched Eighties. He was a casualty in a war—a war that, by the way, continues. Years later I needed money badly and undertook to sell the Basquiat productions I own, but got no takers, since they were too early, failed to display the classic Basquiat look. I’m glad it turned out that way.•

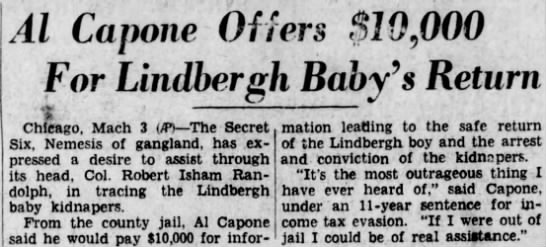

Tags: Al Capone

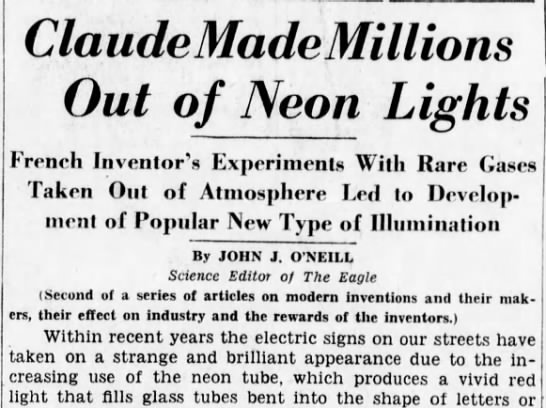

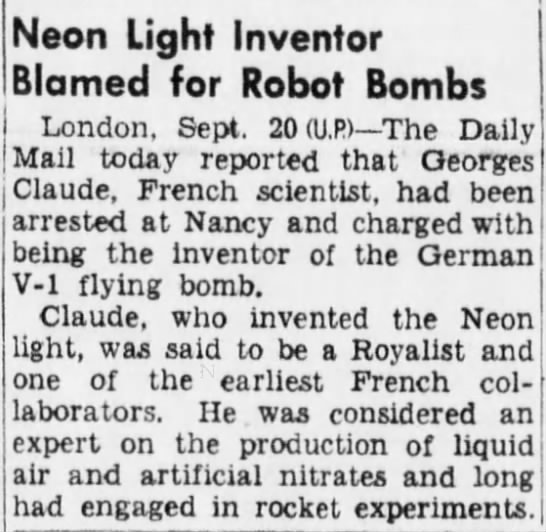

A century ago in France it might have been as apt to refer to Georges Claude as a luminary as anyone else. The inventor of neon lights, which debuted at the Paris Motor Show of 1910, the scientist was often thought of as a “French Edison,” a visionary who shined his brilliance on the world. Problem was, there was a dark side: a Royalist who disliked democracy, Claude eagerly collaborated with the Nazis during the Occupation and was arrested once Hitler was defeated. He spent six years in prison, though he was ultimately cleared of the most serious charge of having invented the V-1 flying bomb for the Axis. Two articles below from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle chronicle his rise and fall.

From February 25, 1931:

From September 20, 1944:

Tags: Georges Claude

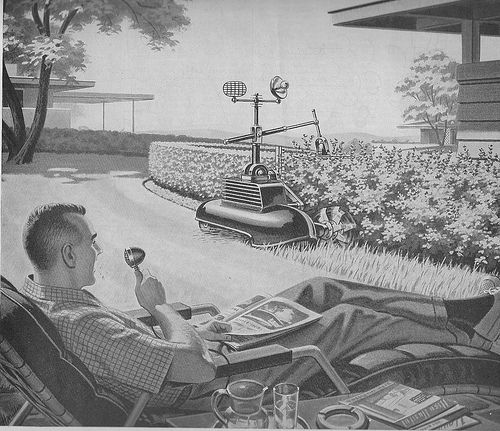

The robots may be coming for our jobs, but they’re not coming for our species, not yet.

Anyone worried about AI extincting humans in the short term is really buying into sci-fi hype far too much, and those quipping that we’ll eventually just unplug machines if they get too smart is underselling more distant dangers. But in the near term, Weak AI (e.g., automation) is far more a peril to society than Strong AI (e.g., conscious machines). It could move us into a post-scarcity tomorrow, or it could do great damage if it’s managed incorrectly.What happens if too many jobs are lost all at once? Will there be enough of a transition period to allow us to pivot?

In a Technology Review piece, Will Knight writes of a Stanford study on AI that predicts certain key disruptive technologies will not have cut a particularly wide swath by 2030. Of course, even this research, which takes a relatively conservative view of the future, suggests we start discussing social safety nets for those on the short end of what may become an even more imbalanced digital divide.

The opening:

The odds that artificial intelligence will enslave or eliminate humankind within the next decade or so are thankfully slim. So concludes a major report from Stanford University on the social and economic implications of artificial intelligence.

At the same time, however, the report concludes that AI looks certain to upend huge aspects of everyday life, from employment and education to transportation and entertainment. More than 20 leaders in the fields of AI, computer science, and robotics coauthored the report. The analysis is significant because the public alarm over the impact of AI threatens to shape public policy and corporate decisions.

It predicts that automated trucks, flying vehicles, and personal robots will be commonplace by 2030, but cautions that remaining technical obstacles will limit such technologies to certain niches. It also warns that the social and ethical implications of advances in AI, such as the potential for unemployment in certain areas and likely erosions of privacy driven by new forms of surveillance and data mining, will need to be open to discussion and debate.•

Tags: Will Knight

Not an original idea: Driverless cars are perfected in the near future and join the traffic, and some disruptive souls, perhaps us, decide to purchase an autonomous taxi and set it to work. We charge less than any competitor, use our slim profits for maintenance and to eventually buy a second taxi. Those two turn into an ever-growing fleet. We subtract our original investment (and ourselves) from the equation, and let this benevolent monster grow, ownerless, allowing it to automatically schedule its own repairs and purchases. Why would anyone need Uber or Lyft in such a scenario? Those outfits would be value-less.

In a very good Vanity Fair “Hive” piece, Nick Bilton doesn’t extrapolate Uber’s existential risk quite this far, but he writes wisely of the technology that may make rideshare companies a shooting star, enjoying only a brief lifespan like Compact Discs, though minus the outrageous profits that format produced.

The opening:

Seven years ago, just before Uber opened for business, the company was valued at exactly zero dollars. Today, it is worth around $68 billion. But it is not inconceivable that Uber, as mighty as it currently appears, could one day return to its modest origins, worth nothing. Uber, in fact, knows this better than almost anyone. As Travis Kalanick, Uber’s chief executive, candidly articulated in an interview with Business Insider, ride-sharing companies are particularly vulnerable to an impeding technology that is going to change our society in unimaginable ways: the driverless car. “The world is going to go self-driving and autonomous,” he unequivocally told Biz Carson. He continued: “So if that’s happening, what would happen if we weren’t a part of that future? If we weren’t part of the autonomy thing? Then the future passes us by, basically, in a very expeditious and efficient way.”

Kalanick wasn’t just being dramatic. He was being brutally honest. To understand how Uber and its competitors, such as Lyft andJuno, could be rendered useless by automation—leveled in the same way that they themselves leveled the taxi industry—you need to fast-forward a few years to a hypothetical version of the future that might seem surreal at the moment. But, I can assure you, it may well resemble how we will live very, very soon.•

Tags: Nick Bilton

Surveillance is a murky thing almost always attended by a self-censorship, quietly encouraging citizens to abridge their communication because maybe, perhaps someone is watching or listening. It’s a chilling of civil rights that happens in a creeping manner. Nothing can be trusted, not even the mundane, not even your own judgement. That’s the goal, really, of such a system–that everyone should feel endlessly observed.

In a Texas Monthly piece, Sasha Von Oldershausen, a border reporter in West Texas, finds similarities between her stretch of America, which feverishly focuses on security from intruders, and her time spent living under theocracy in Iran. An excerpt:

Surveillance is key to the CBP’s strategy at the border, but you don’t have to look to the skies for constant reminders that they’re there. Internal checkpoints located up to 100 miles from the border give Border Patrol agents the legal authority to search any person’s vehicle without a warrant. It’s enough to instill a feeling of guilt even in the most exemplary of citizens. For those commuting daily on roads fitted with these checkpoints, the search becomes rote: the need to prove one’s right to abide is an implicit part of life.

Despite the visible cues, it’s still hard to figure just how all-seeing the CBP’s eyes are. For one, understanding the “realities” of border security varies based on who you talk to.

Esteban Ornelas—a Mexican citizen who was charged with illegal entry into the United States in 2012 and deported shortly thereafter—swears that he was caught was because a friend he was traveling through the backcountry with sent a text message to his family. “They traced the signal,” he told me in his hometown of Boquillas.

When I consulted CBP spokesperson Brooks and senior Border Patrol agent Stephen Crump about what Ornelas had told me, they looked at each other and laughed. “That’s pretty awesome,” Crump said. “Note to self: develop that technology.”

I immediately felt foolish to have asked. But when I asked Pauling that same question, his reply was much more austere: “I can’t answer that,” he said, and left it at that.•

Tags: Sasha Von Oldershausen

Some argue, as John Thornhill does in a new Financial Times column, that technology may not be the main impediment to the proliferation of driverless cars. I doubt that’s true. If you could magically make available today relatively safe and highly functioning autonomous vehicles, ones that operated on a level superior to humans, then hearts, minds and legislation would soon favor the transition. I do think driving as recreation and sport would continue, but much of commerce and transport would shift to our robot friends.

Earlier in the development of driverless, I wondered if Americans would hand over the wheel any sooner than they’d turn in their guns, but I’ve since been convinced we (largely) will. We may have a macro fear of robots, but we hand over control to them with shocking alacrity. A shift to driverless wouldn’t be much different.

An excerpt from Thornhill in which he lists the main challenges, technological and otherwise, facing the sector:

First, there is the instinctive human resistance to handing over control to a robot, especially given fears of cyber-hacking. Second, for many drivers cars are an extension of their identity, a mechanical symbol of independence, control and freedom. They will not abandon them lightly.

Third, robots will always be held to far higher safety standards than humans. They will inevitably cause accidents. They will also have to be programmed to make a calculation that could kill their passengers or bystanders to minimise overall loss of life. This will create a fascinating philosophical sub-school of algorithmic morality. “Many of us are afraid that one reckless act will cause an accident that causes a backlash and shuts down the industry for a decade,” says the Silicon Valley engineer. “That would be tragic if you could have saved tens of thousands of lives a year.”

Fourth, the deployment of autonomous vehicles could destroy millions of jobs. Their rapid introduction is certain to provoke resistance. There are 3.5m professional lorry drivers in the US.

Fifth, the insurance industry and legal community have to wrap their heads around some tricky liability issues. In what circumstances is the owner, car manufacturer or software developer responsible for damage?•

Tags: John Thornhill

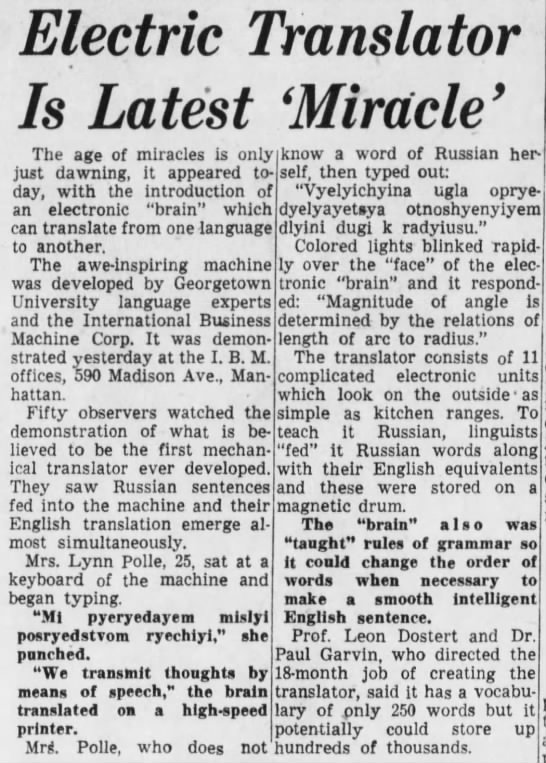

More than six decades ago, long before Siri got her voice, Georgetown and IBM co-presented the first public demonstration of machine translation. Russian was neatly converted into English by an “electronic brain,” the IBM 701, and one of the principals involved, the university’s Professor Leon Dostert, excitedly reacted to the success, proclaiming the demo a “Kitty Hawk of electronic translation.” Certainly the impact from this experiment was nothing close to the significance of the Wright brothers’ achievement, but it was a harbinger of things to (eventually) come. An article in the January 8, 1954 Brooklyn Daily Eagle covered the landmark event.

More than six decades ago, long before Siri got her voice, Georgetown and IBM co-presented the first public demonstration of machine translation. Russian was neatly converted into English by an “electronic brain,” the IBM 701, and one of the principals involved, the university’s Professor Leon Dostert, excitedly reacted to the success, proclaiming the demo a “Kitty Hawk of electronic translation.” Certainly the impact from this experiment was nothing close to the significance of the Wright brothers’ achievement, but it was a harbinger of things to (eventually) come. An article in the January 8, 1954 Brooklyn Daily Eagle covered the landmark event.

Tags: Leon Dostert, Paul Garvin

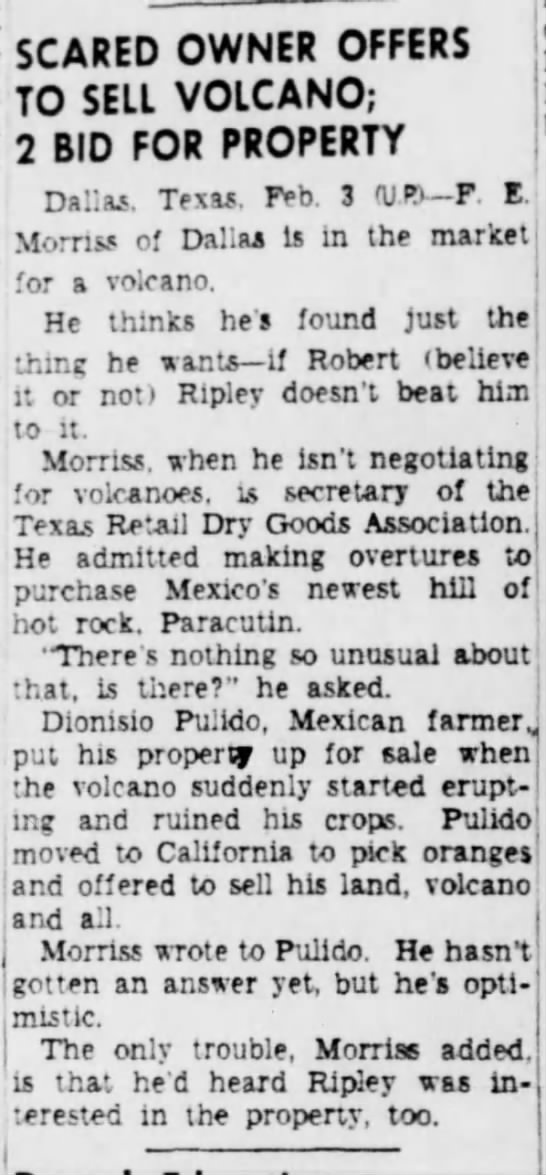

Tags: Dionisio Pulido, F.E. Morriss

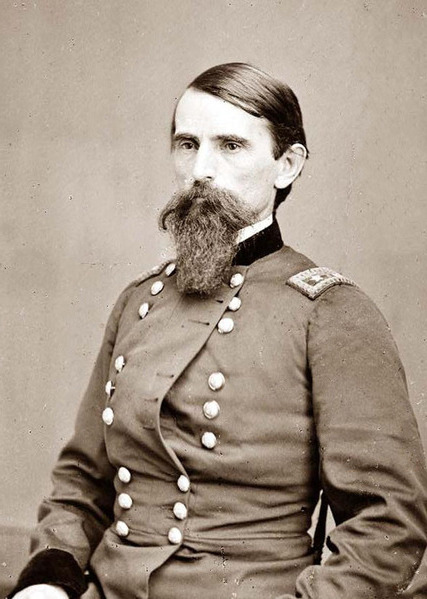

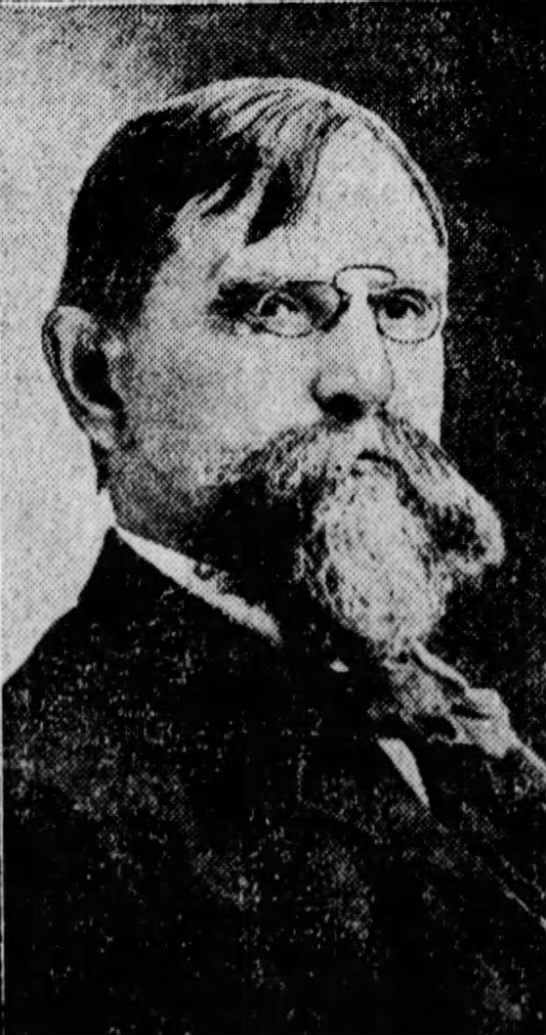

The two best-selling works of fiction in 19th-century America (not counting the Bible) were likely Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. The latter was written by Lew Wallace, a lawyer, diplomat and Union General who became best known as a man of letters. The current film adaptation, a revenge flick, plotzed something fierce at the box office. Perhaps there’s no place for the religious charioteer in a secular age dreaming of driverless cars.

While Wallace was largely a failure as a battlefield commander, he was forceful leader in the area of race relations, arguing against the color line in college football. There weren’t many Americans like him during his age, and they seem in shorter supply now. Wallace’s obituary from the February 16, 1905 edition of the New York Times asserts that he composed his first drafts on a slate and was good for roughly one line a day, which seems impossible if you total his literary output. The opening:

Crawfordsville, Ind.–Gen. Lew Wallace, author, formerly American Minister to Turkey, and veteran of the Mexican and Civil Wars, died at his home in this city to-night, aged seventy-eight years.

The health of Gen. Wallace has been failing for several years, and for months it has been known that his vigorous constitution could not much longer withstand the ravages of a wasting disease.

For more than a year he has been unable to properly assimilate food, and this, together with his advanced age, made more difficult his fight against death. At no time ever has he confessed his belief that the end was near, and his rugged constitution and remarkable vitality have done much to prolong his life.

Gen. Lew Wallace, who years ago achieved widespread distinction as a lawyer, legislator, soldier, author, and diplomat, was a man of exceptionally refined manner, broad culture, and imposing personal appearance. He was a son of David Wallace, who was elected Governor of Indiana by the Whigs in 1837. His birthplace was Brooksville, Franklin County, Ind., where he was born April 10, 1827.

Although Gen. Wallace was famous as a soldier long before he entered the field of letters, it was through his authorship of Ben-Hur and several other popular works that he became known to the largest number of people. Ben-Hur was dramatized eighteen years after the publication of the book, the sale of which in Canada, England, and Continental Europe, as well as in the United States, was tremendous.

As a boy Lew Wallace was a keen lover of books, and his father’s possession of a large library afforded him an opportunity to become acquainted with much of the best literature of the time. From his mother he inherited a love of painting and drawing, but these instincts were overpowered by his desire for a more active life. His mother died when he was only ten years old, and from that time on he refused to submit patiently to restraint. An effort was made to send him to the town school. It was only partially successful. Later his father put him in college at Crawfordsville, but his stay there was brief.

At an early age he commenced the study of law, receiving valuable instruction from his father, and at the end of four years was admitted to the bar. He used to say that the law was the most detestable of all human occupations. It was said that he was unable to prepare a case, but when it came to trial he accepted the statements of his partner as to the law and the evidence and then, following his own convictions to the merits of the case, made an appeal which rarely failed to be effective.•

A common theme in Christoper Mims’ smart WSJ column about the soft launch of sorts of the Internet of Things and Maarten Rikkens’ interesting Research Gate Q&A with The City of Tomorrow author Carlo Ratti is that the future is arriving with a whimper, not a bang. A world enabled by the IoT will be very different even if it doesn’t look any different. You’ll hardly notice it at first blush. You might even forget about it once you do. That’s great for practical matters and less so for issues of privacy. To my mind, that’s always been the promise and peril of such a ubiquitous, essentially invisible network.

From Mims:

Everyone is waiting for the Internet of Things. The funny thing is, it is already here. Contrary to expectation, though, it isn’t just a bunch of devices that have a chip and an internet connection.

The killer app of the Internet of Things isn’t a thing at all—it is services. And they are being delivered by an unlikely cast of characters: Uber Technologies Inc., SolarCity Corp., ADT Corp., andComcast Corp., to name a few. One recent entrant: the Brita unit ofClorox Corp., which just introduced a Wi-Fi-enabled “smart” pitcher that can re-order its own water filters.

Uber and SolarCity are interesting examples. Both rely on making their assets smart and connected. In Uber’s case, that is a smartphone in the hands of a driver for hire. For SolarCity, the company’s original business model was selling electricity directly to homeowners rather than solar panels, which requires knowing how much electricity a home’s solar panels are producing.

Here is another example: On June 23, Comcast said it would acquire a unit of Icontrol Networks Inc., which helps set up smart homes for clients. The company, founded in 2004, prides itself on being “do it for you” instead of “do it yourself,” as are most home-automation systems, says Chief Marketing Officer Letha McLaren.

Understanding that most people want to solve problems without worrying about the underlying technology was crucial, she says.•

From Rikkens:

Question:

Your book mentions that it is increasingly difficult to divorce the physical space from the digital. Does this mean that all aspects of city design should factor in IoT? Or are some aspects of city design divorced from its influence?

Carlo Ratti:

From an architectural point of view, I do not think that the city of tomorrow will look dramatically different from the city of today — much in the same way that the Roman ‘urbs’ is not all that different from the city as we know it today. We will always need horizontal floors for living, vertical walls in order to separate spaces and exterior enclosures to protect us from the outside. The key elements of architecture will still be there, and our models of urban planning will be quite similar to what we know today. What will change dramatically is the way we live in the city, at the convergence of the digital and physical world. IoT will have its biggest impact on the experience of the city, not necessarily its physical form.•

Tags: Charles Owen

For all his hubris, Elon Musk certainly has a noble vision for a better and cleaner world, one in which a species in peril wisely pivots before we’re all buried beneath a global Easter Island. Of course, knowing what should be isn’t the same as making it so. In trying to turn humanity away from using fossil fuels to power its shelter, transportation and commerce, Musk is trying to do on his own what would seem the heaviest lifting even for the biggest states in the world. Colonizing Mars, another of his goals, might be easier.

In an MIT Technology Review piece, Richard Martin suggests Musk may be like Tesla–the man, not the car company–dreaming too big in trying to electrify the world. Other pundits have weighed in on the other end of the spectrum and no one can truly say what the outcome will be, but Musk’s hyper-ambitious goal has always been a long shot, hasn’t it? The most positive scenario that’s also realistic might be that Musk exhorts us to turn to solar and electric, even if his own efforts fail.

From Martin:

Musk’s grand vision for an integrated solar-plus-electric-vehicle behemoth, meanwhile, looks increasingly like a reality distortion field. The opening of the massive solar-panel factory the company is building in Buffalo, New York, has already been pushed back to mid-2017. Some analysts have estimated that the factory is likely to lose as much as $150 million a year once it reaches full production.

What’s more, there is little indication that huge numbers of people are clamoring for the ability to equip their homes with SolarCity panels, a Tesla Powerwall battery, and a charging system for their Teslas. In short, SolarCity’s latest moves could be a signal that merging two companies with combined 2015 losses of $1.6 billion might not be such a great idea after all.

SolarCity and other rooftop solar providers rolled to early success on a river of easy money, as banks, emboldened by generous federal subsidies, showed their willingness to underwrite customer-friendly lease deals. The extension of the investment tax creditlate last year heralded a new phase of strong growth for solar power, but companies like SolarCity and SunEdison, which filed for bankruptcy in April, have had a hard time benefiting from it as their market continues to change underneath them. Mostly ignored in yesterday’s layoff news was a separate filing in which the company said it will offer up to $124 million in “solar bonds”—at terms much less favorable to the company than previous such offerings.SolarCity’s restructuring may well be looked back on as the first wobble that presaged the collapse of Musk’s would-be electric empire.•

Tags: Elon Musk, Richard Martin

The Scientific American piece “20 Big Questions about the Future of Humanity” is loads of fun, setting the huge issues (consciousness, space colonization, etc.) before top-shelf scientists. The only disappointment is University of New Mexico professor Carlton Caves stating that human extinction via machine intelligence “can be avoided by unplugging them.” One can only hope he was being flippant, though it’s not a useful response regardless. Three entries:

1. Does humanity have a future beyond Earth?

“I think it’s a dangerous delusion to envisage mass emigration from Earth. There’s nowhere else in the solar system that’s as comfortable as even the top of Everest or the South Pole. We must address the world’s problems here. Nevertheless, I’d guess that by the next century, there will be groups of privately funded adventurers living on Mars and thereafter perhaps elsewhere in the solar system. We should surely wish these pioneer settlers good luck in using all the cyborg techniques and biotech to adapt to alien environments. Within a few centuries they will have become a new species: the post-human era will have begun. Travel beyond the solar system is an enterprise for post-humans — organic or inorganic.”

—Martin Rees, British cosmologist and astrophysicist3. Will we ever understand the nature of consciousness?

“Some philosophers, mystics and other confabulatores nocturne pontificate about the impossibility of ever understanding the true nature of consciousness, of subjectivity. Yet there is little rationale for buying into such defeatist talk and every reason to look forward to the day, not that far off, when science will come to a naturalized, quantitative and predictive understanding of consciousness and its place in the universe.”

—Christof Koch, president and CSO at the Allen Institute for Brain Science; member of the Scientific American Board of Advisers10. Can we avoid a “sixth extinction”?

“It can be slowed, then halted, if we take quick action. The greatest cause of species extinction is loss of habitat. That is why I’ve stressed an assembled global reserve occupying half the land and half the sea, as necessary, and in my book ‘Half-Earth,’ I show how it can be done. With this initiative (and the development of a far better species-level ecosystem science than the one we have now), it will also be necessary to discover and characterize the 10 million or so species estimated to remain; we’ve only found and named two million to date. Overall, an extension of environmental science to include the living world should be, and I believe will be, a major initiative of science during the remainder of this century.”

—Edward O. Wilson, University Research Professor emeritus at Harvard University•

Tags: Christof Koch, Edward O. Wilson, Martin Rees

If self-appointed Libertarian overlord Grover Norquist, a Harvard graduate with a 13-year-old’s understanding of government and economics, ever had his policy preferences enacted fully, it would lead to worse lifestyles and shorter lifespans for the majority of Americans. He’s so eager to Brownback the whole country he’s convinced himself, despite being married to a Muslim woman, there’s conservative bona fides in Trump’s Mussolini-esque stylings and suspicious math.

In 2014, Norquist made his way to the government-less wonderland known as Burning Man, free finally from those bullying U.S. regulations, the absence of which allows Chinese business titans to breathe more freely, if not literally. Norquist’s belief that the short-term settlement in the Nevada desert is representative of what the nation could be every day is no less silly than considering Spring Break a template for successful marriage. He was quote as saying: “Burning Man is a refutation of the argument that the state has a place in nature.” Holy fuck, who passed him the peyote? Norquist wrote about his experience in the Guardian. Maileresque reportage, it was not. An excerpt:

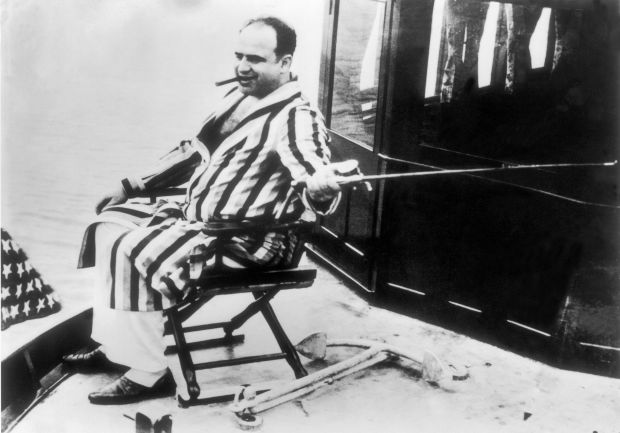

You hear that Burning Man is full of less-than-fully-clad folks and off-label pharmaceuticals. But that’s like saying Bohemian Grove is about peeing on trees or that Chicago is Al Capone territory. Burning Man is cleaner and greener than a rally for solar power. It has more camaraderie and sense of community than a church social. And for a week in the desert, I witnessed more individual expression, alternative lifestyles and imaginative fashion than …. anywhere.

The demand for self-reliance at Burning Man toughens everyone up. There are few fools, and no malingerers. People give of themselves – small gifts like lip balm or tiny flashlights. I brought Cuban cigars. Edgy, but not as exciting as some “gifts” that would have interested the federal authorities.

I’m hoping to bring the kids next year.

On my last day of my first Burning Man, at the Reno airport, a shoeless man (he had lost his shoes in the desert) was accosted by another dust-covered Burner carrying sneakers: “Take these,” he said. “They are my Burning Man shoes.” The shoeless man accepted the gift with dignity.•

In an excellent Financial Times piece, Tim Bradshaw broke bread in San Francisco with Larry Harvey, co-founder of Burning Man and its current “Chief Philosophic Officer,” who speaks fondly of rent control and the Bernie-led leftward shift of the Democratic Party. Grover Norquist would not approve, even if Harvey is a contradictory character, insisting he has a “conservative sensibility” and lamenting the way many involved in social justice fixate on self esteem. An excerpt:

I ask if he feels, after 30 years, that Burning Man’s ideals are starting to be felt beyond the desert. “I’d like to mischievously quote Milton Friedman,” he says, invoking the rightwing economist. “He said change only happens in a crisis, and then that actions that are undertaken depend on the ideas that are just lying around.” With the “discontents of globalisation” set to continue, he predicts that crisis will hit by the middle of this century. “I think there really is a chance for sudden change.” However, I struggle to pin him down on exactly which Burners’ ideas he hopes will be “lying around” when it does.

Most Burners are fond of recalling tall tales of fake-fur-clad excess, elaborately customised “art cars” and monster sound systems. This year’s art installations include a 50-ft “space whale”, the head and hands of a giant man appearing to rise from the sand, and part of a converted Boeing 747 that its new owners say is now a “mover of dreams”. Harvey likes to survey the art — and the rest of his creation — from a high platform close to the centre of the event at First Camp, the founders’ HQ. But instead of recounting hedonistic tales, he is much more eager to talk about organisational details, such as Black Rock City’s circular layout, “sort of like a neolithic temple”.

Indeed, Harvey insists he has a “conservative sensibility” and is “not a big fan of revolution”. “Do I sound like a hippie? I’m not!” And he bristles at being called anti-capitalist, although he hung out with the hippies on Haight Street in 1968. “I was there in the spring, autumn and winter of love, but I missed the summer,” he says, due to being drafted into the US army. “It was apparent to me that it was all based on what Tom Wolfe called ‘cheques from home’. The other source that shored it up was selling dope. I thought, that isn’t sustainable.”•

Tags: Larry Harvey, Tim Bradshaw

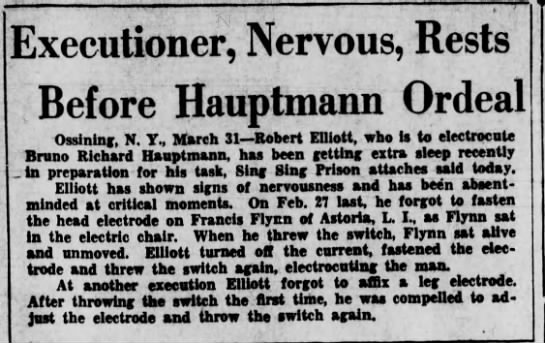

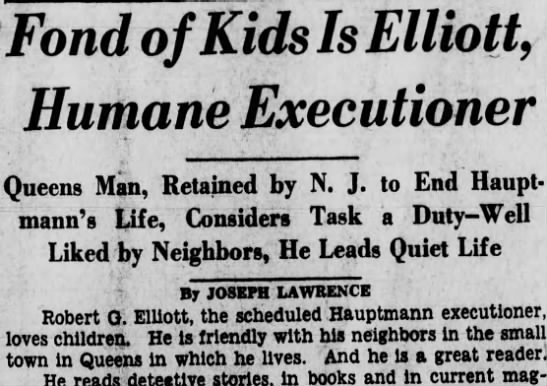

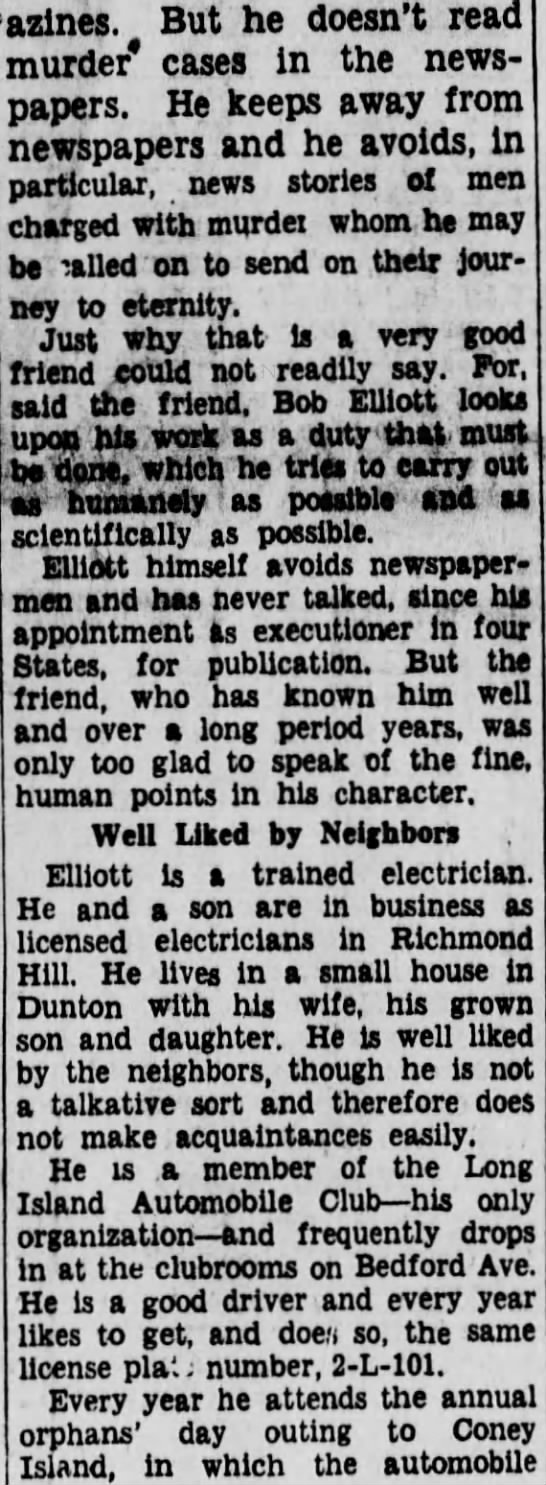

Bruno Hauptmann’s executioner, Robert G. Elliott, became increasingly anxious as the fateful hour neared, and you could hardly blame him. Who knows what actually happened to the Lindbergh baby, but the circumstances were crazy, with actual evidence intermingling with that appeared to be the doctored kind. To this day, historians and scholars still argue the merits of Hauptmann’s conviction. Elliot who’d also executed Sacco & Vanzetti and Ruth Snyder, was no stranger to high-profile cases, but the Lindbergh case may still be the most sensational in American history, more than Stanford White’s murder or O.J. Simpson’s race-infused trial.

Elliott, whose title was the relatively benign “State Electrician” of New York had succeeded in the position John W. Hulbert, who was so troubled by his job and fears of retaliation, he committed suicide. Elliott, who came to be known as the “humane executioner” for devising a system that minimized pain, was said to be a pillar of the community who loved children and reading detective stories. A friend of his explained the Elliott’s general philosophy regarding the lethal work in a March 31, 1936 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article, just days before Hauptmann’s demise: “It is repulsive to him to have to execute a woman, but he feels that, after all, he’s just a machine.” Such rationalizations were necessary since Elliott claimed to be fiercely opposed to capital punishment, believing the killings accomplished nothing.

Tags: Bruno Hauptmann, Robert G. Elliott

Either there’s a collective delusion among those racing to successfully complete driverless capability (not impossible), or we’re going to have autonomous vehicles on roads and streets in the next decade.

If that time frame proves correct, these self-directing autos will hastily make redundant taxi, rideshare, bus, truck and delivery drivers and wreak havoc on the already struggling middle class. That doesn’t mean progress should be unduly restrained, but it does mean we’re going to have to develop sound policy answers.

Not everyone is going to be able to transition into coding or receive a Machine Learning Engineer nanodegree from Udacity. That’s just not realistic. Because of Washington gridlock, we’ve bypassed a golden opportunity to rebuild our infrastructure at near zero interest over the last eight years. It may soon be imperative to push forward not only to save fraying bridges but also faltering Labor.

Excerpts follow from: Maya Kosoff’s Vanity Fair “Hive” piece about Ford’s ambitious plans for wheel-less cars by 2021, and 2) Max Chafkin’s Bloomberg Businessweek article on Uber’s driverless fleet launching this year in Pittsburgh.

From Kosoff:

The world of autonomous vehicles is riddled with hypotheticals. It’s not immediately clear when Uber and Lyft will have self-driving cars (or what will happen to their drivers when they do), but both companies have made it clear that at some point, they see autonomous ride-hailing fleets as the future of their business. The same can be said about Tesla, Google’s self-driving cars, Apple’s top-secret car project, and automakers like General Motors, which haspartnered with Lyft. All these companies must first face novel regulatory hurdles, and few have given the public a hard deadline for when they can expect to see self-driving cars on the road.

Ford, however, is breaking from the pack and marking a date on its calendar: 2021, the carmakerannouncedTuesday. Ford’s self-driving cars won’t have gas or brake pedals or a steering wheel, the company says. And the car is being made specifically for ride-hailing services—it seems Ford is trying to out-Uber Uber. (Uber, for its part,unveiled a self-driving Ford Fusionearlier this year, andreportedlyapproached a number of automakers about partnerships, before taking astrategic investmentfrom Toyota.)

Five years isn’t much time to get a fully-functioning, fully-autonomous vehicle to market, but Ford is moving quickly.•

From Chafkin:

Near the end of 2014, Uber co-founder and Chief Executive Officer Travis Kalanick flew to Pittsburgh on a mission: to hire dozens of the world’s experts in autonomous vehicles. The city is home to Carnegie Mellon University’s robotics department, which has produced many of the biggest names in the newly hot field. Sebastian Thrun, the creator of Google’s self-driving car project, spent seven years researching autonomous robots at CMU, and the project’s former director, Chris Urmson, was a CMU grad student.

“Travis had an idea that he wanted to do self-driving,” says John Bares, who had run CMU’s National Robotics Engineering Center for 13 years before founding Carnegie Robotics, a Pittsburgh-based company that makes components for self-driving industrial robots used in mining, farming, and the military. “I turned him down three times. But the case was pretty compelling.” Bares joined Uber in January 2015 and by early 2016 had recruited hundreds of engineers, robotics experts, and even a few car mechanics to join the venture. The goal: to replace Uber’s more than 1 million human drivers with robot drivers—as quickly as possible.

The plan seemed audacious, even reckless. And according to most analysts, true self-driving cars are years or decades away. Kalanick begs to differ. “We are going commercial,” he says in an interview with Bloomberg Businessweek. “This can’t just be about science.”

Starting later this month, Uber will allow customers in downtown Pittsburgh to summon self-driving cars from their phones, crossing an important milestone that no automotive or technology company has yet achieved.•

Tags: Max Chafkin, Maya Kosoff