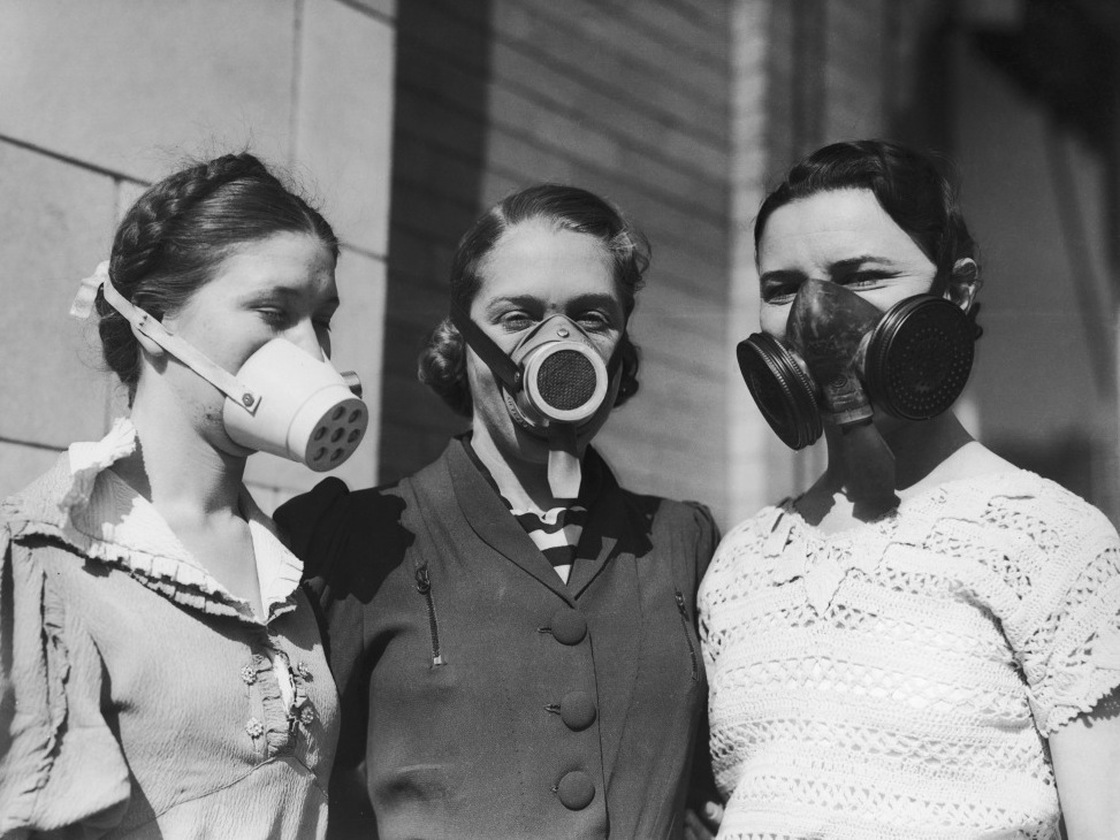

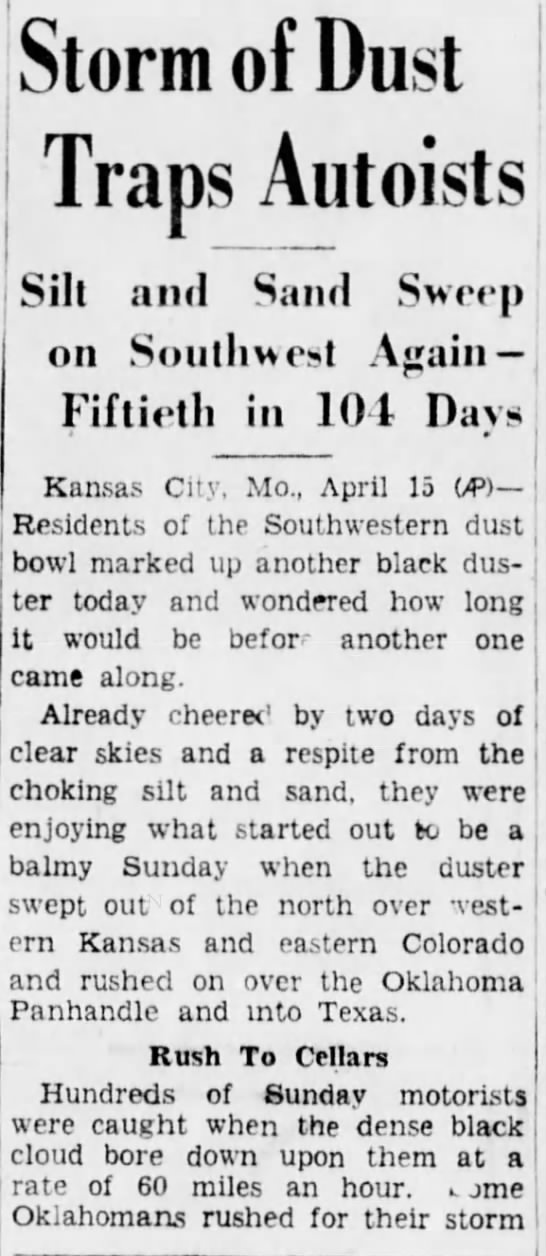

The Dust Bowl of the 1930s was situated in the American prairies, but the ramifications of the poor farming methods were wide, and the storms soon swept east and obscured the sun over the entire Atlantic seaboard. I thought of what was known as the “Black Blizzards” because I just read Michael Tennesen’s The Next Species, a very interesting book about the potential end of us. The author draws an analogy between the Depression Era dust storms and what may occur in Las Vegas if the crust of the nearby desert floor dissipates, something that’s possible because of the havoc we’re playing with the environment. The difference between boom town and ghost town can be decided by the tiniest particles. A year after the first wave of the storms in 1934, mayhem was still the order of the day, as this article from the April 15, 1935 Brooklyn Daily Eagle can attest.

You are currently browsing the archive for the Science/Tech category.

Tags: Michael Tennesen

Google Glass’ douche factor was insurmountable. But what if functions were contained in a tiny contact lens that was undetectable?

One such innovation, which doesn’t have nearly the number of uses of Sergey Brin’s eyewear but does provide telescopic vision, is nearly upon us. From Robert J. Szczerba at Forbes:

For those of us old enough to remember television in the ‘70s the epitome of cool was the Six Million Dollar Man, Col. Steve Austin and his bionic enhancements. But what was once the purview of science fiction is inching closer to becoming an everyday reality, as optics specialist Eric Tremblay unveiled a unique contact lens that provides the user with telescopic vision. The lens was revealed earlier this year at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in San Jose, California.

The new contact lens, a more advanced model of a prototype introduced in 2013, is 1.55 millimeters thick and features a very thin, reflective telescope, which allows the user to zoom in and out in literally a wink. The telescopic contacts are made with a rigid lens known as a scleral lens— larger in diameter than the more familiar soft contacts, but useful for special cases, such as for people with irregularly shaped corneas. Despite their size and stiffness, scleral lenses are safe and comfortable for special applications, and are an attractive platform for technologies such as optics, sensors, and electronics.•

Tags: Eric Tremblay, Robert J. Szczerba

Salespeople at companies I have worked for: Scientologists, cokeheads, pathological liars, a fuckface who rang a cowbell each time a deal closed, a lady who loudly worried about the state of her “ta-tas” prior to meeting clients, and one guy so creepy I think about him each time I hear of a string of Craigslist hooker murders.

No, they weren’t all that bad, but the goal of having an in-house staff of highly professional salespeople at every single business is likely unrealistic. Could this department be reimagined, perhaps outsourced, even Uberized?

In a Wall Street Journal article, Christopher Mims writes about the growing momentum of sales as a contingent position, a potential further fractionalization of the job pool. The opening:

Right now a college student in Sweden—let’s call him Sven—has a rather unusual summer job. He’s in sales, but he hasn’t met anyone from the company whose products he pushes.

His boss is an app. It considers Sven’s strengths and weaknesses as a salesman, matches him with goods from any of a dozen brands, and plots a route through Stockholm optimized to include as many potential customers as possible in the time allotted to him.

The app is like Uber, but for a sales force. It has many of the same dynamics: Companies can use it to get salespeople on demand, and those salespeople choose when to work and which assignments to accept. The startup behind it, Universal Avenue, calls the idea “sales as a service.”

While the Stockholm-based company may be pioneering this model of it, outsourcing functions traditionally considered integral to a business is a trend that’s gaining steam with certain types of companies.

Anyone who needs to put salespeople in front of potential customers who aren’t otherwise economical to reach can do so, it seems, by combining the magic of a remote workforce and fractional employment.•

Tags: Christopher Mims

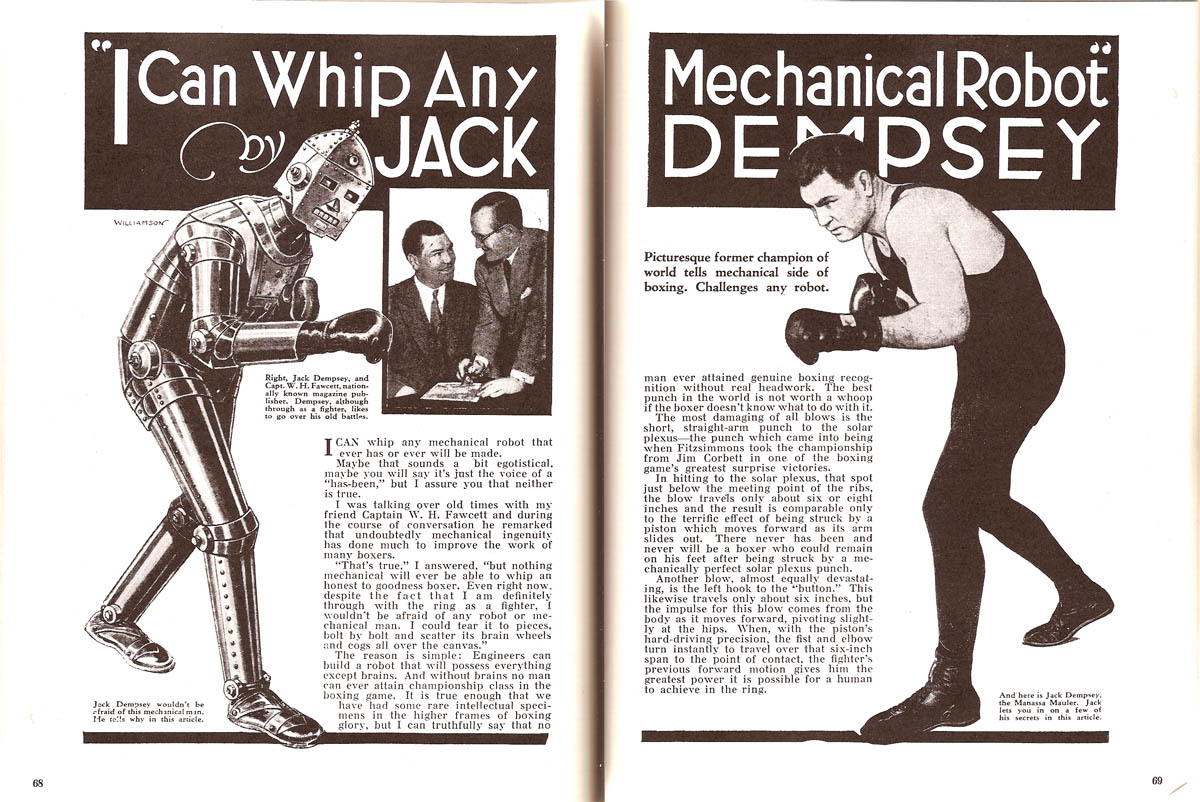

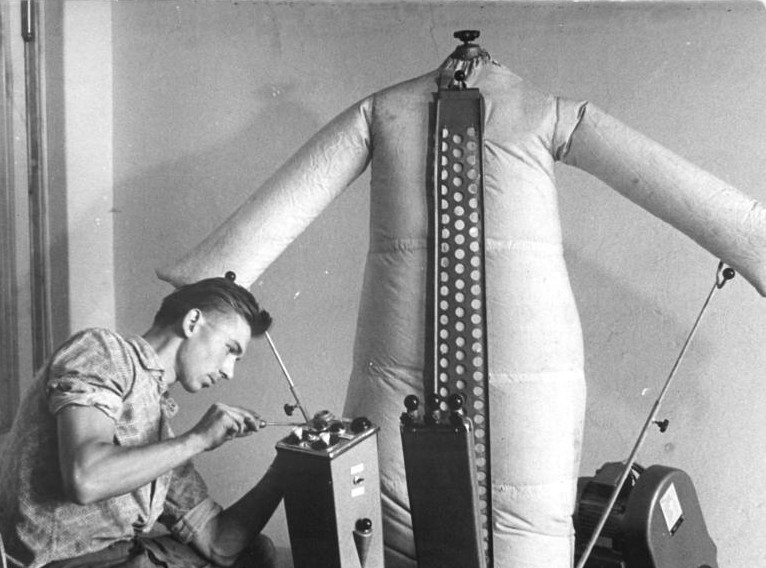

Of all the great things robotics have brought to our lives, Der Boxroboter is responsible for none of them. The aforementioned fighting machine was a German-manufactured 1980s sparring partner promised to be an alloy Ali. Watch it jab in the video below at the 20:35 mark. From a 1987 Sports Illustrated piece:

The German Democratic Republic is very advanced in the use of scientific training methods for its athletes. Now the East Germans have beaten the world to the punch in the sport of boxing. Meet Der Boxroboter, a GDR-designed-and-built computerized robot that can hang in there with the best of fighters for hours on end. ”It’s tough to find good sparring partners, especially for heavyweights,” says Dieter Seala of the GDR trade mission, which plans to market DBs internationally for a little more than $33,000 apiece. ”Human sparring partners get tired after a few rounds. They get punched too many times and lose their consistency.”

DB is not just a Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em robot. It can be programmed to assume any fighting style — attack the upper body, go for the belly, back an opponent into a corner — and is allegedly quicker across the ring than any human boxer. DB is equally adept at throwing rights and lefts and has great wheels (literally).•

The popularity of dystopic culture, I believe, is far more complicated than a fear of the world ending. We’re not really worried about things falling apart but that they might not.

Part of the allure of apocalypse entertainments is that we get to, if briefly and virtually, quiet the hum of progress, the noise of the new technologies. There’s a deeply buried anxiety within us that the world will continue apace–perhaps at an accelerated pace–leaving most of us in its wake. The death of development on screens and in pages is a relief of sorts, something we crave, not dread.

In his latest Medium piece, “Optimism Doesn’t Sell,” Jeff Jarvis, who sees the Google Glass as half full, writes about the box-office failing of Disney’s future-positive Tomorrowland:

Much of the dystopianism that surrounds us today is about our machines and the companies that run them: how Google makes us stupid, Facebook kills privacy, Google Glass turns us all into peeping Toms, robots will take our jobs and our car keys, the internet of things will open the door to crime, and artificial intelligence will bring unspecified dangers (the juiciest kind).

But the truth is that dystopianism is rarely about technology. It’s about people. The dystopian fears that his fellow man and woman are too stupid to use technology well, too gullible to see its risks, too timid to control its dangers, too venal to see beyond its temptations.

Dystopianism is the ultimate statement of hubris: ‘I am smarter than the rest of you,’ says the profound pessimist. ‘I can see where you are all going wrong. I can see that you can’t learn. I am better than you all.’

Like game shows, reality TV, and gawking at Walmart shoppers, dystopianism is mostly an excuse for making fun of your neighbors and feeling superior to them. They’re so stupid they’re ruining the future.•

Tags: Jeff Jarvis

Libertarianism is supposed to be having a moment in America, but Edward Luce of the Financial Times argues that it’s Socialism that really is. I’ll certainly disagree with the columnist’s depiction of Martin O’Malley as a “left winger” (he’s a pragmatist in the Clinton mold), but it is worth thinking back on the collapse of the Soviet Union. At that moment, it seemed capitalism had ultimately triumphed. What if capitalism leads to robotics so profound that technological unemployment brings about the end of capitalism? Or at least a radical redefining of it? Not impossible.

Luce’s opening:

Leftwing politicians are in electoral retreat across most of the western world. The one exception is the United States. At 15 per cent in the Democratic polls, Bernie Sanders, the senator from Vermont, is riding higher than any US socialist since Eugene Debs ran for the White House a century ago.

The fact that Mr Sanders has very little chance of unseating Hillary Clinton is beside the point. His popularity is dragging her leftward. If he flames out, other left-wingers, such as Martin O’Malley, the former governor of Maryland who entered the race at the weekend, are ready to pick up the baton. Elizabeth Warren, the populist Massachusetts senator, will continue to prod Mrs Clinton from outside the field. The more Mrs Clinton adopts their language, the harder it will be for her to reclaim the centre ground next year. Yet she is only following the crowd. A surprisingly large chunk of Democrats are happy to break the US taboo against socialism.

To most students of US politics, the phrase American socialism is an oxymoron — like clean coal or the Bolivian navy. A century ago, Werner Sombart, a German scholar, asked “Why is there no socialism in America?” It was a question that confounded Marxists. As the most advanced capitalistic society, the US was most ripe for a proletarian revolution, according to their teleology.

Yet the US refused to live up to its role.•

Tags: Edward Luce

When Thomas Friedman devised his Golden Arches Theory of war, he somehow forgot that humans aren’t rational creatures. Our decisions are often perplexing, and the few among us who make sober, clear-headed calculations are frequently viewed as something other than human. What’s wrong with them?

In a Bloomberg View piece about Richard Thaler’s professional memoir, Misbehaving, Michael Lewis writes of an economist who had a simple-yet-significant epiphany: We make screwy choices, often to our own detriment.

An excerpt:

At any rate, in addition to calculating the market’s price for a human life, Thaler got distracted by how much fun he might have if he asked actual human beings how much they needed to be paid to run the risk of dying. He began with his own students, telling them to imagine that by attending his lecture, they had exposed themselves to a rare fatal disease. There was a 1 in 1,000 chance they had caught it. There was a single dose of the antidote: How much would they be willing to pay for it?

Then he asked them the same question, in a different way: How much would they demand to be paid to attend a lecture in which there is a 1 in 1,000 chance of contracting a rare fatal disease, for which there was no antidote?

The questions were practically identical, but the answers people gave to them were — and are — wildly different. People would say they would pay two grand for the antidote, for instance, but would need to be paid half a million dollars to expose themselves to the virus. “Economic theory is not alone in saying that the answers should be identical,” writes Thaler. “Logical consistency demands it. … To an economist, these findings are somewhere between puzzling and preposterous. I showed them to (his thesis adviser) and he told me to stop wasting my time and get back to work on my thesis.”

Instead, Thaler began to keep a list of things that people did that made a mockery of economic models of rational choice. There was the guy who planned to go to the football game, changed his mind when he saw it was snowing, and then, when he realized he had already bought the ticket, changed his mind again. There was the other guy who refused to pay $10 to have someone mow his lawn but wouldn’t accept $20 to mow his neighbor’s. There was the woman who drove 10 minutes to a store in order to save $10 on a $45 clock radio but wouldn’t drive the same amount of time to save $10 on a $495 television. There were the people Thaler invited over to dinner, to whom he offered, before dinner, a giant bowl of nuts. They ate so many nuts they had no appetite for the far more appealing meal. The next time they came to dinner Thaler didn’t offer nuts — and his guests were happier.•

Tags: Michael Lewis, Richard Thaler

It’s a shame Freeman Dyson has gotten into a spitting match with people perplexed with his views on climate change (I’ve sometimes been one of them), and made intemperate comments on the topic, because having read his work extensively, it certainly seems he cares deeply about conservation and biodiversity. It’s just one of the stranger aspects of a distinguished scientific and writing career.

On another topic: Here’s the opening of Dyson’s latest NYRB piece, a brief essay about the new Taschen book, Expanding Universe, a spectacular collection of photography enabled by the Hubble Telescope, in which the writer marvels over how tiny particles can be more overwhelming than fully-formed bodies:

When we see things for the first time, the pictures are always a surprise. Nature’s imagination is richer than ours. We imagine things to be simple and Nature makes them complicated. In Expanding Universe, a magnificent selection of pictures taken by cameras on the Hubble Space Telescope, the big surprise is dust. We imagined a universe of stars and galaxies gleaming brightly against a black sky. What we see is multicolored patterns of fluid motion, looking like eddies in a river or clouds in a sunset. The patterns are made of dust. Dust is made of tiny solid grains of carbon and rock and metals. The grains condense out of cooling interstellar gas, just as grains of smoke condense out of cooling flames over a forest fire. Most of what we see in the universe is dust. The reason is simple. We see only the surfaces of things, so that things appear big in our pictures when they have a big surface area. Dust has far more surface area than stars or planets. That is why the most striking pictures in this book are pictures of dust. It is not accidental that the editors chose to print on the jacket a spectacular picture of a huge dustcloud giving birth to newborn stars in the constellation Carina.•

Tags: Freeman Dyson

In a fascinating New York Times article, Liz Alderman reports on the ghost companies of Europe, phantom businesses with pretend inventory and customers, which exist merely to supply (unpaid) make-believe jobs to the long-term unemployed, novice workers who need experience or those retraining for new industries.

Considered broadly, such an arrangement already exists all over the globe, although not with the express mission of helping citizens back into the workforce. A massive number of people already have fake, non-paying jobs in the Freeconomy. Each day, hundreds of millions create content for Facebook, which would make the company the largest sweatshop in world history, if it paid even a nominal amount. Should technological unemployment become widespread, become the new normal, we’ll continue to produce content and products, even if there’s no compensation. Maybe we’ll receive “free” minutes or bonus points or nothing at all. But for that to happen in a large-scale and permanent way, we’ll have to start taxing capital rather than labor, and there will need to be a guaranteed basic income.

The opening of Alderman’s piece:

At 9:30 a.m. on a sunny weekday, the phones at Candelia, a purveyor of sleek office furniture in Lille, France, rang steadily with orders from customers across the country and from Switzerland and Germany. A photocopier clacked rhythmically while more than a dozen workers processed sales, dealt with suppliers and arranged for desks and chairs to be shipped.

Sabine de Buyzer, working in the accounting department, leaned into her computer and scanned a row of numbers. Candelia was doing well. Its revenue that week was outpacing expenses, even counting taxes and salaries. “We have to be profitable,” Ms. de Buyzer said. “Everyone’s working all out to make sure we succeed.”

This was a sentiment any boss would like to hear, but in this case the entire business is fake. So are Candelia’s customers and suppliers, from the companies ordering the furniture to the trucking operators that make deliveries. Even the bank where Candelia gets its loans is not real.

More than 100 Potemkin companies like Candelia are operating today in France, and there are thousands more across Europe. In Seine-St.-Denis, outside Paris, a pet business called Animal Kingdom sells products like dog food and frogs. ArtLim, a company in Limoges, peddles fine porcelain. Prestige Cosmetique in Orleans deals in perfumes. All these companies’ wares are imaginary.

These companies are all part of an elaborate training network that effectively operates as a parallel economic universe.•

Tags: Liz Alderman

It’s not exactly the most pressing concern to sort out how we’d conduct justice should it become possible for humans to upload consciousness to computers and attain a sort-of immortality for our sort-of selves. But it may be theoretically possible and makes for a fun bull session, so Conor Friedersdorf penned a well-written cautionary essay on the topic for the Atlantic, which also considers other unintended consequences of the endless summer. An excerpt:

It’s not exactly the most pressing concern to sort out how we’d conduct justice should it become possible for humans to upload consciousness to computers and attain a sort-of immortality for our sort-of selves. But it may be theoretically possible and makes for a fun bull session, so Conor Friedersdorf penned a well-written cautionary essay on the topic for the Atlantic, which also considers other unintended consequences of the endless summer. An excerpt:

Radical life extension would so scramble and confound our normal notions of justice that there’s no telling how future Americans would react to the new reality. Historic monsters might be punished for 6 million years … or just three or four times longer than a 150-year sentence a U.S. court imposed on this obscure money-launderer. It’s hard to speculate even when confining ourselves to descendants of ours, in this country, with moral codes closely resembling our own.

In fact, it isn’t clear how we’d react right now.

If today’s Americans magically took custody of servers containing the disembodied consciousnesses of every figure ever mentioned in the country’s newspapers, going back to the beginning, would we stop at punishing former Nazi leaders? Would there be a protest movement to hold Native American killers and slaveholders accountable? What about the folks behind the Tuskegee syphilis experiment? Or the city leaders of towns in the Jim Crow South that subjugated blacks?•

Tags: Conor Friedersdorf

Of all the poems I read as child, Carl Sandburg’s “Chicago” is the one that stays with me most: “Hog Butcher, Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat, Player with Railroads.” No place of a complicated nature could ask for a better defense.

Today, Chicago, like most global cities, is more complicated still, a home to stunning wealth inequality, a place of thriving and one of falling, and one connected more to ideas than geography. It’s not just crowded with markets but a market itself.

At the Financial Times, Edward Luce writes of its “two-city tale.” The opening:

They call Chicago the city of big shoulders. Much like Dubai’s emergence from virtually nowhere in the last 20 years to become a global city, Chicago pulled itself up from its bootstraps in the mid-19th century to turn into America’s industrial hub.

Unlike its peers — Detroit, Cleveland and Baltimore — it survived the obliteration of America’s industrial heartlands in the past 40 years by learning to “pour new wine into old bottles,” in the words of Richard Longworth, a leading chronicler of today’s Chicago. Where once it thrived on slaughtered hogs, smelted iron and freight trains, now it hosts corporate headquarters, boasts new economy start-ups and links to other global hubs via O’Hare airport. Today’s Chicago prefers to benchmark itself against Shanghai, São Paulo, Paris — and, yes, Dubai. But is it paying too little heed to what is under its nose?

The fate of a city’s hinterland is one that haunts every great metropolis. For London, it is the rest of the UK which sometimes feels like a different country. For Dubai, it is the Wahhabi heartlands of the Arabian peninsula. For Chicago it is the US Midwest.

In the past, Chicago acted as the locomotive of its hinterlands — in Mr Longworth’s words — buying the Midwest’s farm produce and other raw commodities and then converting them into products. The city was linked umbilically to its surrounding geography and vice versa. Today, it mostly hovers above its hinterlands. But in some ways it is also parasitic on them. Much like the giant sucking sound of London hoovering up the UK’s talent, Chicago takes the best and the brightest from the small towns of America and plugs them into the global economy. Chicago’s success is no longer symbiotic with its rural neighbours. In some ways it comes at their expense.•

Tags: Edward Luce

It’s more than 40 years since research and development began on the Compact Disc, exactly 30 years since the technology’s amazing rise in popularity and more than a decade since the best market the recording industry ever enjoyed started to lose its groove. How did the biggest music companies in the world not see that the information would become pure? It’s the same old story: They didn’t want to accept it would happen because they didn’t want the huge profits to stop coming.

In “How the Compact Disc Lost Its Shine,” Dorian Lynskey of the Guardian has a smart, sprawling article about the brief dominance of a medium. Three excerpts follow.

_________________________

Bootleg CDs were a danger the industry could get its head around – you could hold one in your hand. What it couldn’t comprehend was the threat of the MP3: the idea that music could transcend physical formats. “That happened for two reasons,” says [How Music Got Free author Stephen] Witt. “One was they were enjoying unbelievable profits. Two, the studio engineers hated the way the MP3 sounded and refused to engage with it. A lot of artists hated the way it sounded, too.” What the audiophiles didn’t realise was that most consumers couldn’t tell the difference. “What was the audio experience before the compact disc?” says Witt. “It was cheap vinyl or an AM transistor radio on the beach, and MP3 sounds better than either of those.”

_________________________

Just like their predecessors in Greece in 1982, 90s executives were too busy worrying about the next quarter to consider the next decade. The status quo was perfect, until it wasn’t. “My biggest bugbear about this industry is that they all think short-term,” says Webster. “Nobody ever thinks long-term. All these executives were sitting there being paid huge bonuses on increased profits and they didn’t care. I don’t think anyone saw it coming. I remember the production guy at Virgin saying, ‘In a few years, you’re going to be able to carry all the music you want around on something the size of a credit card.’ And we all laughed. Don’t be ridiculous! How can you do that?”

_________________________

Only a handful of people predicted the CD’s downfall way back in 1982. German computer engineer Dieter Seitzer, the forefather of the MP3, immediately considered the CD “a maximalist repository of irrelevant information, most of which was ignored by the human ear,” writes Witt. If music could become digital data, he thought, it wouldn’t be bound by the Red Book. Webster remembers one industry Cassandra, Maurice Oberstein – who ran CBS and then Polygram in the UK – making a similar point. “He was the only one who went: ‘We’re making a huge mistake. We’re putting studio-quality masters into the hands of people.’ And he was absolutely right in that respect. Once you made a CD with ones and zeroes it was only a matter of time before that was converted into something that was easily transferable.”

The fall of the CD, like its rise, began slowly.•

Tags: Dorian Lynskey, Stephen Witt

The scientists at CERN working on the Large Hadron Collider are asking some scary questions, but it isn’t easy for the layperson to wrap his or her head around the undertaking. In a Reddit Ask Me Anything, in which a multinational group of LHC workers answered questions, a couple of exchanges with nuclear physicist Federico Ronchetti cut through some of the nebulousness.

_________________________

Question:

Explain to me like I am five: why are you doing this and what makes it important? What could we/you do with this data in the future?

Federico Ronchetti:

i can give you an example. in 1800 the study of electricity and magnetism were considered an highly theoretical study with no practical uses. at most was used for circus shows. once understood by means of theory and experiments it shaped the modern world. try to think how could you live without electricity. the research we are carrying out at cern may seem far from everyday life today however will bring forward our knowledge of the natural phenomena and it has already practical spin offs. for instance accelerator technology is used for inoperable cancer surgery and as you may know the software protocol that powers the web was invented at cern.

_________________________

Question:

What are some of the long term practical applications you can envision for this research? Feel free to go wild.

Federico Ronchetti:

you may have heard about project for reaching mars or even for deep space travel. one showstopper there is propulsion. we won’t get very far with chemical thrusters. fully understanding the nature of fundamental forces may pave the way for a new kind of engine that can power deep space exploration. however developing space technologies is not a current research topic at CERN.•

Tags: Federico Ronchetti

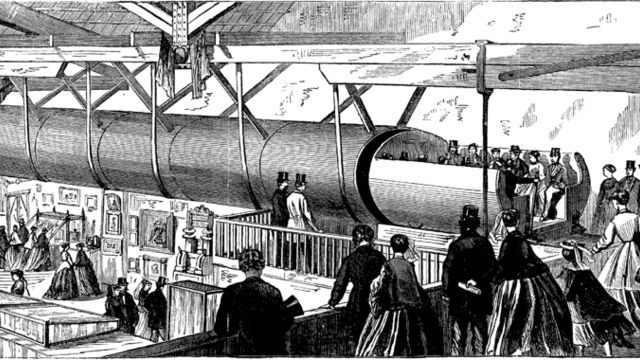

The Hyperloop might be built and might be free if it is built. Developers of Elon Musk’s futuristic transportation system are seeking ways to vanish customer costs since it will have to be heavily traveled if it’s to become a large-scale success.

From Katie Collins at Wired UK:

Even though Hyperloop’s pricing consultants estimate a ride will cost twice the price of a plane ticket, [CEO Dirk] Ahlborn is keen to avoid this situation. “We want to make it something you use every single day many times,” he says. He is even debating whether “ticketing is best way of monetising, or are there other ways to make money?”.

“I really, strongly believe that if we create a hyperloop network and it’s free — in the off-peak times at least, in peak times we would charge a little bit — but we make money in other ways, that will really change how people live.”

There are already some options for this; for a start, the system works on 100 percent renewable energy, and actually will make more energy than it needs. As such, says Ahlborn, “we will actually be able to sell the energy.” He’s also looking for ideas for alternative ways in which the Hyperloop might be able to make money.•

Tags: Dirk Ahlborn, Elon Musk

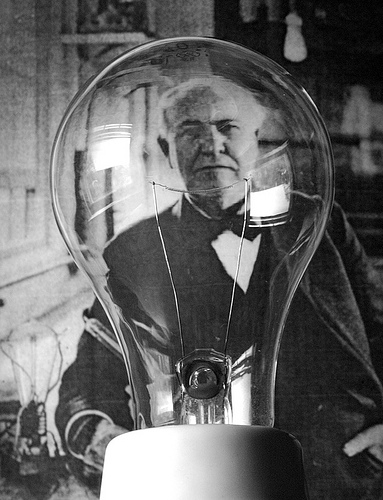

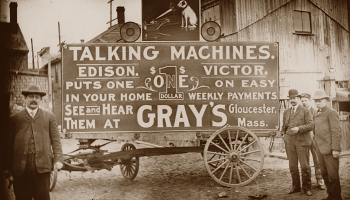

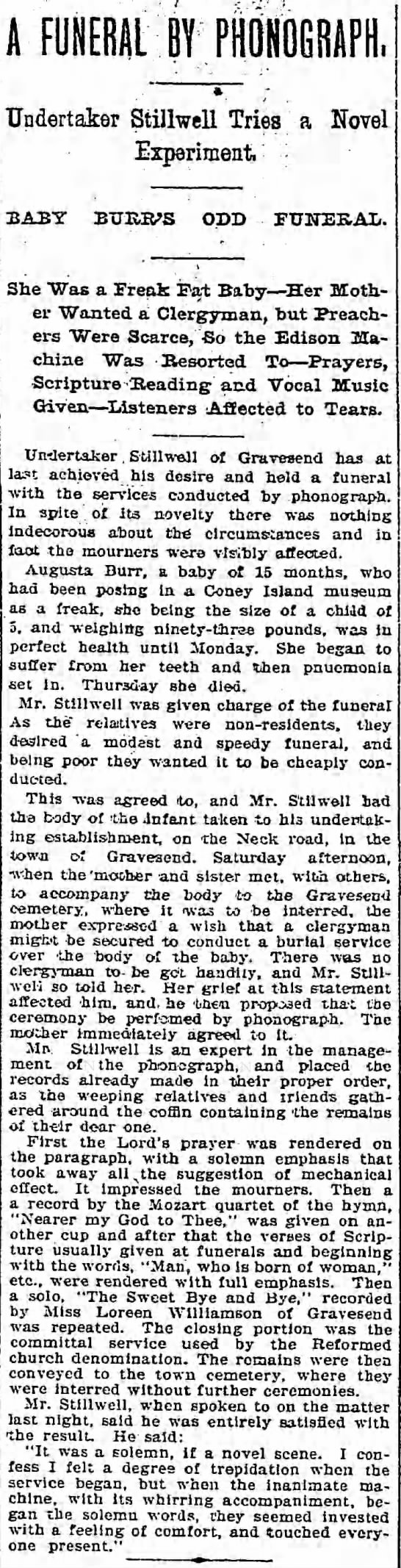

The phonograph was initially a disappointing technology commercially, even if Thomas Edison was something of a smash when he demonstrated his “talking machine” in London in 1888. One nineteenth-century Brooklyn undertaker, however, found a novel use for the new contraption during the funeral of young freak-show performer. An article in the August 18, 1895 Brooklyn Daily Eagle described the unconventional ceremony.

Tags: Augusta Burr, Undertaker Stillwell

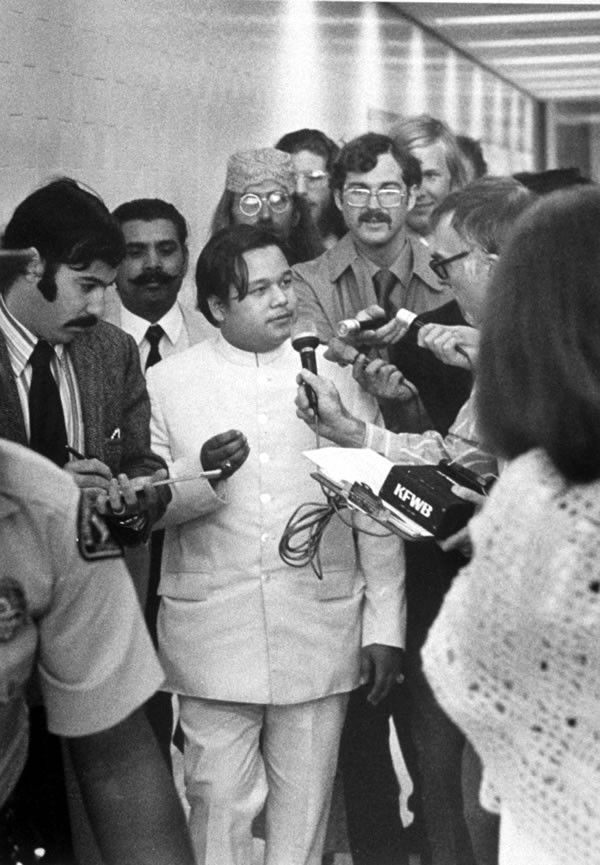

In 1973, the former child preacher Marjoe Gortner was hired by OUI, a middling vagina periodical of the Magazine Age, to write a deservedly mocking article about the American visit of another youthful religious performer, the 16-year-old Maharaj Ji, an adolescent Indian guru who promised to levitate the Houston Astrodome, a plot that never got off the ground. Two excerpts from the resulting report published the following May, which revealed a tech-friendly and futuristic cult leader, who would have been right at home in today’s Silicon Valley.

____________________________

The guru’s people do the same thing the Pentecostal Church does. They say you can believe in guru Maharaj Ji and that’s fantastic and good, but if you receive light and get it all within, if you become a real devotee-that is the ultimate. In the Pentecostal Church you can be saved from your sins and have Jesus Christ as your Saviour, but the ultimate is the baptism of the Holy Ghost. This is where you get four or five people around and they begin to talk and more or less chant in tongues until sooner or later the person wanting the baptismal experience so much-well, it’s like joining a country club: once you’re in, you’ll be like everyone – else in the club.

The people who’ve been chanting say, “Speak it out, speak it out,” and everything becomes so frenzied that the baptismalee will finally speak a few words in tongues himself, and the people around him say, “Oh, you’ve got it.” And the joy that comes over everybody’s faces! It’s incredible. It’s beautiful. They feel they have got the Holy Spirit like all their friends, and once they’ve got it, it’s forever. It’s quite an experience.

So essentially they’re the same thing pressing on your eyes while your ears are corked, and standing around the altar speaking in tongues. They’re both illuminating experiences. The guru’s path is interesting, though. Once you’ve seen the light and decided you want to join his movement, you give over everything you have–all material possessions. Sometimes you even give your job. Now, depending on what your job is, you may be told to leave it or to stay. If you stay, generally you turn your pay checks over to the Divine Light Mission, and they see that you are housed and clothed and fed. They have their U. S. headquarters in Denver. You don’t have to worry about anything. That’s their hook. They take care of it all. They have houses all over the country for which they supposedly paid cash on the line. First class. Some of them are quite plush. At least Maharaj Ji’s quarters are. Some of the followers live in those houses, too, but in the dormitory-type atmosphere with straw mats for beds. It’s a large operation. It seems to be a lot like the organization Father Divine had back in the Thirties. He did it with the black people at the Peace Mission in Philadelphia. He took care of his people-mostly domestics and other low-wage earners–and put them up in his own hotel with three meals a day.

The guru is much more technologically oriented, though. He spreads a lot of word and keeps tabs on who needs what through a very sophisticated Telex system that reaches out to all the communes or ashrams around the country. He can keep count of who needs how many T-shirts, pairs of socks–stuff like that. And his own people run this system; it’s free labor for the corporation.

____________________________

The morning of the third day I was feeling blessed and refreshed, and I was looking forward to the guru’s plans for the Divine City, which was soon going to be built somewhere in the U. S. I wanted to hear what that was all about.

It was unbelievable. The city was to consist of ‘modular units adaptable to any desired shape.’ The structures would have waste-recycling devices so that water could be drunk over and over. They even planned to have toothbrushes with handles you could squeeze to have the proper amount of paste pop up (the crowd was agog at this). There would be a computer in each communal house so that with just a touch of the hand you could check to see if a book you wanted was available, and if it was, it would be hand-messengered to you. A complete modern city of robots. I was thinking: whatever happened to mountains and waterfalls and streams and fresh air? This was going to be a technological, computerized nightmare! It repulsed me. Computer cards to buy essentials at a central storeroom! And no cheating, of course. If you flashed your card for an item you already had, the computer would reject it. The perfect turn-off. The spokesman for this city announced that the blueprints had already been drawn up and actual construction would be the next step. Controlled rain, light, and space. Bubble power! It was all beginning to be very frightening.•

____________________________

“The Houston Astrodome will physically separate itself from the planet which we call Earth and will fly.”

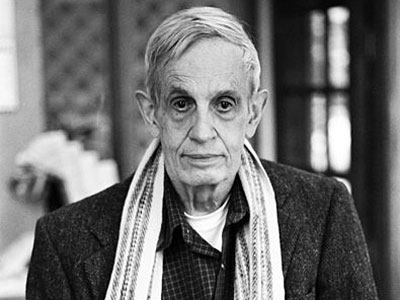

I think the best postscript I’ve read to the unfortunate auto crash that just claimed the lives of John and Alicia Nash is the Q&A Zachary A. Goldfarb of the Washington Post conducted with Sylvia Nasar, author of the wonderful book about the mathematician, A Beautiful Mind, which was masterfully adapted for the screen by Akiva Goldsman. In one exchange, Nasar reminds that even the relatively happy third act of Nash’s life was complicated. An excerpt:

Zachary A. Goldfarb:

How did he spend the last 21 years, since he won the Nobel?

Sylvia Nash:

The first time I saw him was a few months after he won the Nobel, and he was going to a game theory conference in Israel. He was surrounded by other mathematicians, and he looked like someone who had been mentally ill. His clothes were mismatched. His front teeth were rotted down to the gums. He didn’t make eye contact. But, over time, he got his teeth fixed. He started wearing nice clothes that Alicia could afford to buy him. He got used to being around people.

He and Alicia spent a lot of their time taking care of their son, Johnny, and doing the things that are so ordinary that the rest of us don’t think about them. Once I asked him what difference the Nobel Prize money made, and he literally said, “Well, now I can go into Starbucks and buy a $2 cup of coffee. I couldn’t do that when I was poor.” He got a driver’s license. He had lunch most days with other mathematicians, reintegrating into the one community that mattered to him most.

The last time I was with him was about a year ago when Alicia organized a really lovely dinner with us and two other couples. John was talking about all the invitations they’ve gotten and all the places they’ve planned to travel. Johnny was there. He was still very sick. They took him to a lot of the places they went and always tried to include him. Their life was a mix of glamour and celebrity – and the day-to-day which revolved around Johnny, who by then was in his 50s and was as sick as his father ever was and entirely dependent on them.•

Tags: Alicia Nash, John Nash, Sylvia Nasar, Zachary A. Goldfarb

In a Medium piece, Gerald Huff answers the points made by writer Walter Isaacson and roboticist Pippa Malmgren during a recent London debate, in which they argued against the likelihood of large-scale technological unemployment. Isaacson touting work created by the so-called Sharing Economy, contingent jobs which squeeze laborers, was either his least-researched response or most disingenuous one.

From Huff:

What is different about the technologies emerging now from academia and tech companies large and small is the extent to which they can substitute for or eliminate jobs that previously only humans could do. Over the course of thousands of years, human brawn was replaced by animal power, then wind and water power, then steam, internal combustion and electric motors. But the human brain and human hands — with their capabilities to perceive, move in and manipulate unstructured environments, process information, make decisions, and communicate with other people — had no substitute. The technologies emerging today — artificial intelligence fed by big data and the internet of things and robotics made practical by cheap sensors and massive processing power — change the equation. Many of the tasks that simply had to be done by humans will in the coming decades fall within the capabilities of these emerging technologies.

When Isaacson says “it always has, and I submit always will produce more jobs, because it produces…more things that we can make and buy” he is falling into the Labor Content Fallacy. Without repeating the entire argument in the linked article, there is no law of economics that says a product or service must require human labor. The simplest example is a digital download of a song or game, which has essentially zero marginal labor content. In the coming decades, for the first time in history, we will be able to “make and buy” a huge variety of goods and services without the need to employ people. The historical correlation between more human jobs due to increased demand for goods and services from a rising population will be broken.•

Tags: Gerald Huff, Pippa Malmgren, Walter Isaacson

Even before the Internet, we’ve always been inside a hive mind of sorts, things have forever “gone viral” in one sense or another, though technology has made such functions more immediate, intricate and seamless. Of course, we’re only at the beginning. What becomes of us as individuals if our brains are always “plugged in” and we become a true neural collective, if our gray matter moves from “dial-up” to “broadband”? It will create new problems even as it helps solve many others.

A passage from “Hive Consciousness,” Peter Watts’ new Aeon essay:

Cory Doctorow’s novel Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom(2003) describes a near future in which everyone is wired into the internet, 24/7, via cortical link. It’s not far-fetched, given recent developments. And the idea of hooking a bunch of brains into a common network has a certain appeal. Split-brain patients outperform normal folks on visual-search and pattern-recognition tasks, for one thing: two minds are better than one, even when they’re in the same head, even when limited to dial-up speeds. So if the future consists of myriad minds in high-speed contact with each other, you might say: Yay, bring it on.

I’m not sure that’s the way it’s going to happen, though.

I don’t necessarily buy into the hokey old trope of an internet that ‘wakes up’. Then again, I don’t reject it out of hand, either. Google’s ‘DeepMind’, a general-purpose AI explicitly designed to mimic the brain, is a bit too close to SyNAPSE for comfort (and a lot more imminent: its first incarnations are already poised to enter the market). The bandwidth of your cell phone is already comparable to that of your corpus callosum, once noise and synaptic redundancy are taken into account. We’re still a few theoretical advances away from an honest-to-God mind meld – still waiting for the ultrasonic ‘Neural Dust’ interface proposed by Berkley’s Dongjin Seo, or for researchers at Rice University to perfect their carbon-nanotube electrodes – but the pipes are already fat enough to handle that load when it arrives.

And those advances may come easier than you’d expect. Brains do a lot of their own heavy lifting when it comes to plugging unfamiliar parts together. A blind rat, wired into a geomagnetic sensor via a simple pair of electrodes, can use magnetic fields to navigate a maze just as well as her sighted siblings. If a rat can teach herself to use a completely new sensory modality – something the species has never experienced throughout the course of its evolutionary history – is there any cause to believe our own brains will prove any less capable of integrating novel forms of input?

Not even skeptics necessarily deny the likelihood of ‘thought-stealing technology.’•

Tags: Peter Watts

In the IEET essay “Aristotle, Robot Slaves, and a New Economic System,” philosopher John G. Messerly uses Jaron Lanier’s Who Owns the Future? as a jumping-off point for a discussion of how we’ll live should we experience a critical mass of technological unemployment. Messerly is largely sanguine, predicting we’ll still enjoy life when we’re second best, the way we continue to play chess despite being checkmated by our silicon sisters. Of course, he doesn’t explain how we’ll get from here to there, how we will come to “share the wealth.” It may not be such a smooth transition.

An excerpt:

I think that Lanier is on to something. We can think of the non-automated work as anything from essential to frivolous. If we think of it as frivolous, then so too are the people that produce it. If we don’t care about human expression in art, literature, music, sport or philosophy, then why care about the people that produce it.

But even if machines write better music or poetry or blogs about the meaning of life, we could still value human generated effort. Even if machines did all of society’s work we could still share the wealth with people who wanted to think and write and play music. Perhaps people just enjoy these activities. No human being plays chess as well as the best supercomputers, but people still enjoy playing chess; I don’t play golf as good as Tiger Woods, but I still enjoy it.

I’ll go further. Suppose someone wants to sit on the beach, surf, ski, golf, smoke marijuana, watch TV, or collect coins. What do I care? Perhaps a society comprised of contented people doing what they wanted would be better than one informed by the Protestant work ethic. A society of stoned, TV watching, skiers, golfers and surfers would probably be a happier one than we live in now. (The evidence shows that the happiest countries are those with the strongest social safety nets, the ones with the most paid holidays and generous vacation and leave policies; the Western European and Scandinavian countries.) People would still write music and books, lift weights, volunteer, and visit their grandchildren. They would not turn into drug addicts!

This is what I envision.•

Tags: Jaron Lanier, John G. Messerly

Cultured meat isn’t happening today or tomorrow–even those with a vested interest don’t believe it will be commercially viable for at least two decades–but the cost of an in vitro burger has already fallen precipitously from its 2013 price of $325K (condiments included). When taste and price become reasonable, it will be a real market, and one that will destabilize the slaughterhouse and be far less damaging to the environment than the beef industry.

From Ariel Schwartz at Fact Company:

The artificial burger that you—or your science-fiction-loving friends—have been waiting for is real. And now it’s cheap, too.

It wasn’t long ago that test-tube hamburgers—meat made from small pieces of lab-grown animal muscle tissue—were just a glimmer in some mad scientist’s eye. Then, in 2013, the dream of an artificial burger suddenly got interesting. That’s when Mark Post, a researcher at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, announced that he had created a burger made from real meat grown in a lab (20,000 strips of muscle tissue, to be exact) for the unreasonable price of $325,000. Now that price has dropped to just over $11 for a burger ($80 per kilogram of meat), according to a recent ABC News interview with Post.•

Tags: Ariel Schwartz, Mark Post

I’ve barely read any science fiction in my life even though I read constantly. That’s a bad thing to admit, right?

In Ed Finn’s Slate interview with Neal Stephenson, tied to the publication of his latest novel, Seveneves, the author briefly comments on the existential threats we face. The exchange:

Question:

The story is a meditation on existential threats to the species. Having not so long ago founded Hieroglyph, a project dedicated to optimism, what do you think we should be most worried about and how do you see our chances?

Neal Stephenson:

Well, aside from the threat of a big asteroid impact, the thing that we should be worried about is climate change, which is going to happen. There’s no way to make it not happen now. I think that dwarfs everything else.

Question:

Do you see yourself as essentially an optimist in the long-range survival of the species?

Neal Stephenson:

Yes, I think that we’ve got the prerequisites that we need in the way of technical know-how and resources. There’s a lot of energy. There’s a lot of stuff for us to work with. Solving problems has become a kind of routine operation, and so now it’s really a matter of organizing people in some way that doesn’t have terrible side effects.•

Tags: Ed Finn, Neal Stephenson

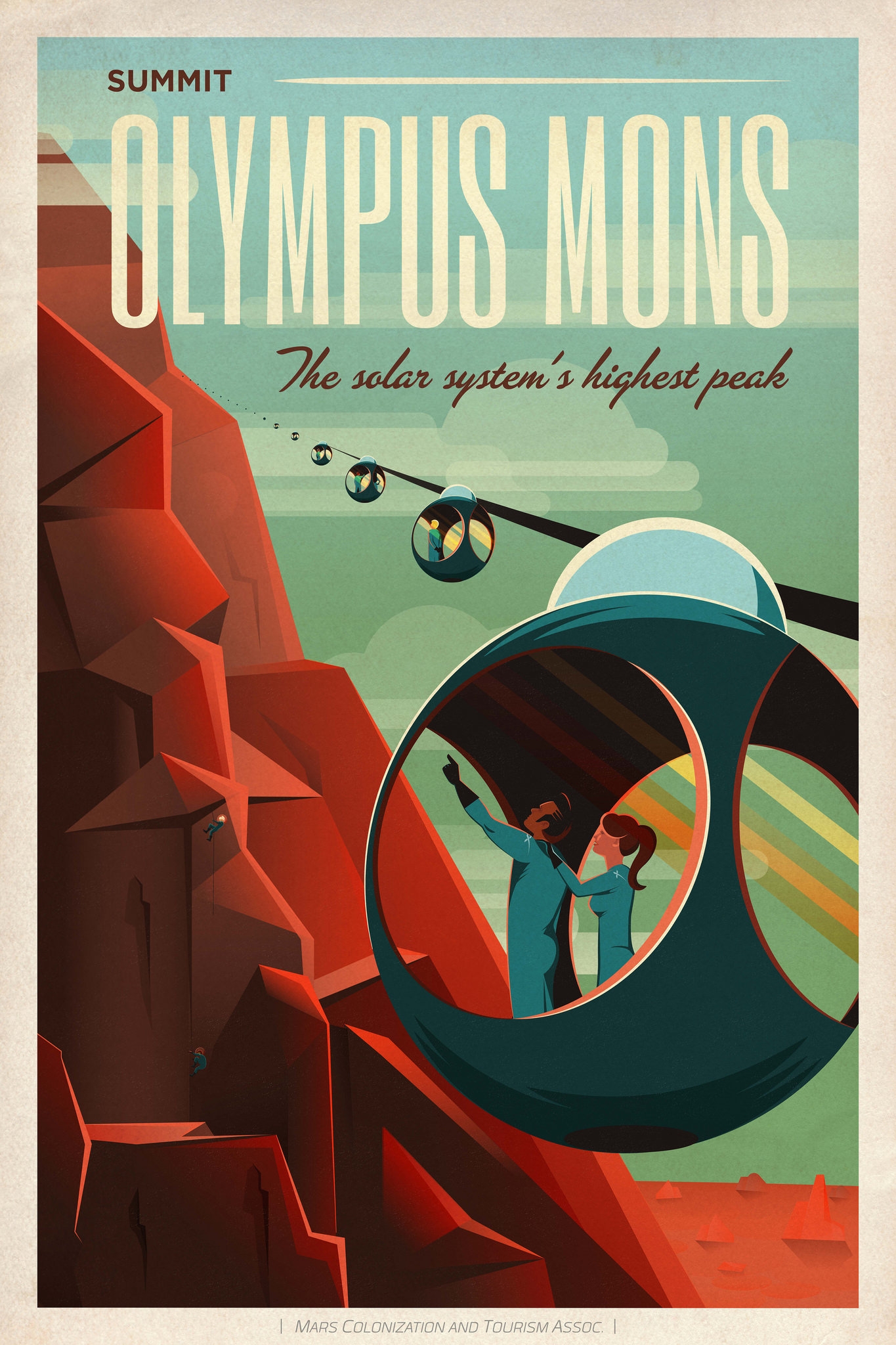

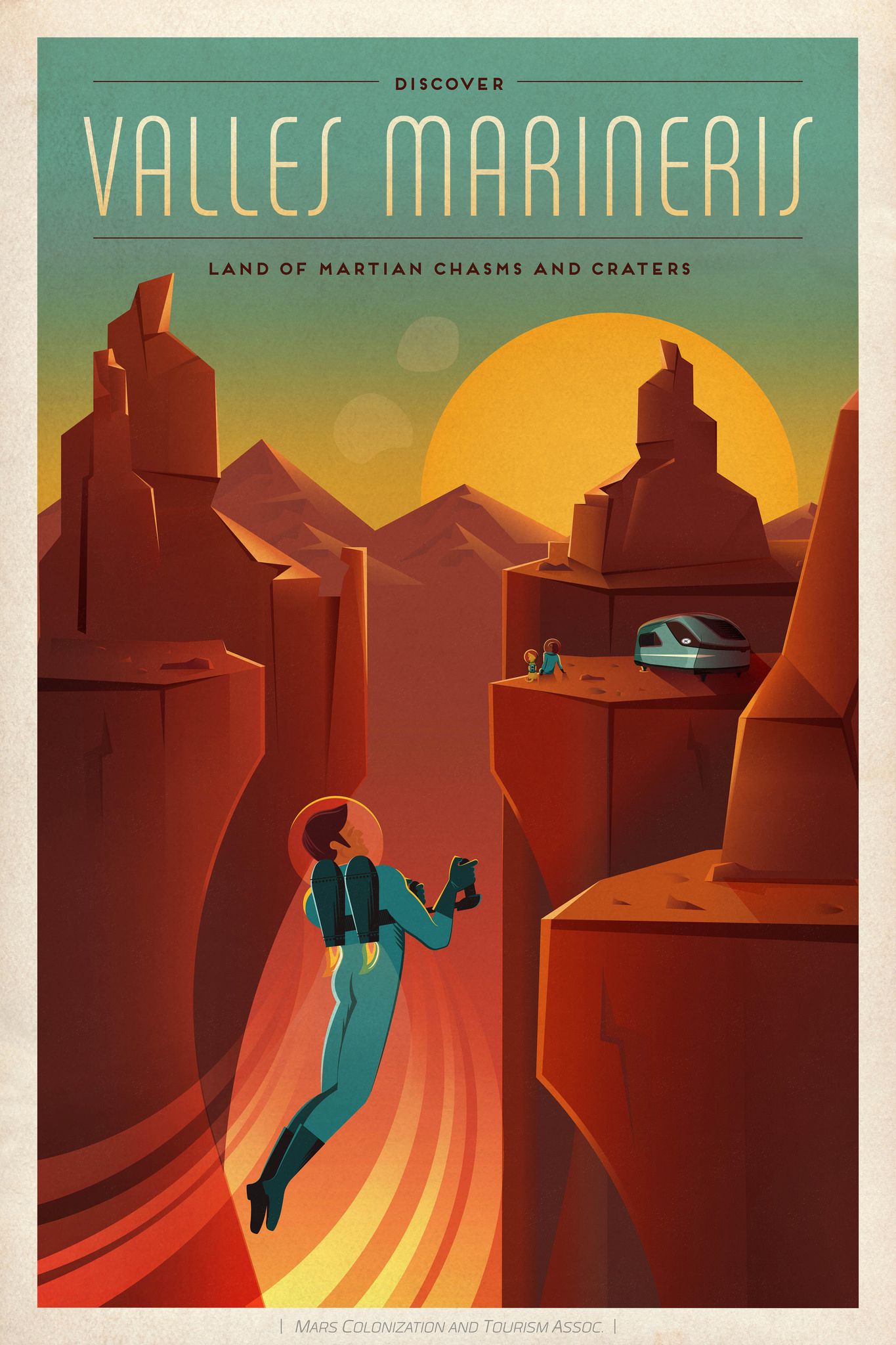

“Militarized Space Race” doesn’t have a comforting ring to it, but Neil deGrasse Tyson (mischievously) asserts that’s what the U.S. and China need to engage in to kickstart in earnest a voyage to Mars. Perhaps.

I don’t know that the fear of China is the same as it was with Russia during the Cold War. I mean, we’re practically partners with China, and they’re good communists capitalists just like we are. Ultimately, I don’t know if it matters which nation gets there first. The whole world benefited from Apollo even if the bragging rights and flag-planting were awfully sweet. Would a competition between the two leading economies work better than the nations agreeing to work together to get to Mars ASAP? Perhaps the competition should be between government and private industry instead? Us vs. Musk?

From Chris Zappone of the Sydney Morning Herald:

In the search to find the high-paying jobs and industries of the future, Neil deGrasse Tyson has an idea for a novel solution. How about a militarised space race to Mars?

More specifically, the famed American astrophysicist says that if he could just get China’s leaders to leak a memo to the West about plans to build military bases on Mars, “the US would freak out and we’d all just build spacecraft and be there in 10 months.”

The fallout of such competition would, like the Space Race of yore, alter the technological focus of advanced economies, likely helping shake off the current period of low growth and innovation stagnation in favour of new industries for the future.“This would reignite the flames of innovation that I think we, at least in the US, at one time took for granted,” Tyson told Fairfax Media from New York. And while Tyson offers his plan for Mars with tongue firmly planted in cheek, the issue of growing an economy through more science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) is no joke. …

In fact, the dazzling feats of humans in space would change the broader culture of a country.

“You would transform a sleepy country into an innovation nation and you’d do it practically overnight. And that transformation has huge economic implications,” he says.•

Tags: Chris Zappone, Neil deGrasse Tyson

This has already been a remarkably rich year for new books, but the best one I’ve read so far is Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens. Dense with ideas and beautifully written, it’s a dazzling, wide-ranging look at how we came to be the only human species on Earth, and how that may very well change in the future. The Guardian has a cheeky piece succinctly explaining Harari’s feelings regarding cyborgism. An excerpt:

What did he say? “I think it is likely in the next 200 years or so homo sapiens will upgrade themselves into some idea of a divine being, either through biological manipulation or genetic engineering or by the creation of cyborgs, part-organic part non-organic.”

Aren’t historians supposed to talk about the past, mainly? Yes, and Harari does also do that. He reckons that great fictions such as religion and money have been the key to humanity’s success because they made people function in large, flexible communities.

I see. Can I have his royalty cheques, then? I suggest you ask him about that. He also thinks these fictions are now reaching their limits because technology will make rich people amortal and virtually all-powerful, meaning that they won’t need God any more.

What’s amortal? It means, theoretically, you could live for ever, as long as someone doesn’t get annoyed and smash you up.

Far from guaranteed, I should think. And how will technology accomplish this? Well, you could have intelligent nanobots injected into your blood to rejuvenate your cells and repair any damage. You could implant a computer and various utensils into your body, giving you superhuman powers. Or you could just simply upload your mind into a computer so you could exist anywhere and experience anything.•

Tags: Yuval Harari Noah

Robert Bigelow wants to be a realtor to the stars–literal stars.

The Space Act just passed by Congress makes it legal (in this country, at least) for U.S. companies to keep anything they mine from asteroids, other planets, etc. The entrepreneur Bigelow wants the government to go further and give him permission to develop inflatable real estate on a patch of the moon.

From Brian Fung at the Washington Post:

Under the SPACE Act, which just passed the House, businesses that do asteroid mining will be able to keep whatever they dig up:

Any asteroid resources obtained in outer space are the property of the entity that obtained such resources, which shall be entitled to all property rights thereto, consistent with applicable provisions of Federal law.

This is how we know commercial space exploration is serious. The opportunity here is so vast that businesses are demanding federal protections for huge, floating objects they haven’t even surveyed yet. …

Technically the FAA’s jurisdiction covers launches and reentries only — but under a request from hotel and aspiring aerospace mogul Robert Bigelow, that power could grow.

You see, Bigelow wants to experiment with inflatable habitats that will allow people to live in space. By getting an FAA launch license that gives him access to space, Bigelow would be able to stake out an exclusive piece of the moon.

Space law experts believe that this exclusive territory could be very, very big. That’s because under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, crewed vehicles are entitled to operate inside a 125-mile “non-interference” zone designed to keep astronauts safe, Joanne Gabrynowicz, the former editor of the Journal of Space Law, told Harvard Political Review. If the same standard were applied to commercial space operations on lunar or other extraterrestrial bodies, then Bigelow could become a leader in the first major land rush of outer space.•

Tags: Brian Fung, Robert Bigelow