“Progress isn’t always a straight line,” exclaimed President Obama in the wake of our stunning 2016 Presidential election, clinging as best he could to the audacious hope that always floated him in the past. He probably could have safely gone a step further and said that it never moves in a straight line, progress and regress always coexisting, even in the brightest and darkest moments.

“Progress isn’t always a straight line,” exclaimed President Obama in the wake of our stunning 2016 Presidential election, clinging as best he could to the audacious hope that always floated him in the past. He probably could have safely gone a step further and said that it never moves in a straight line, progress and regress always coexisting, even in the brightest and darkest moments.

· · ·

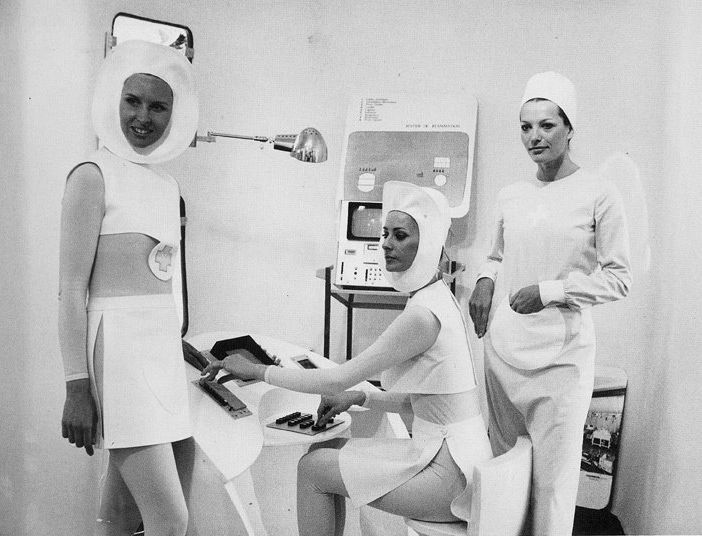

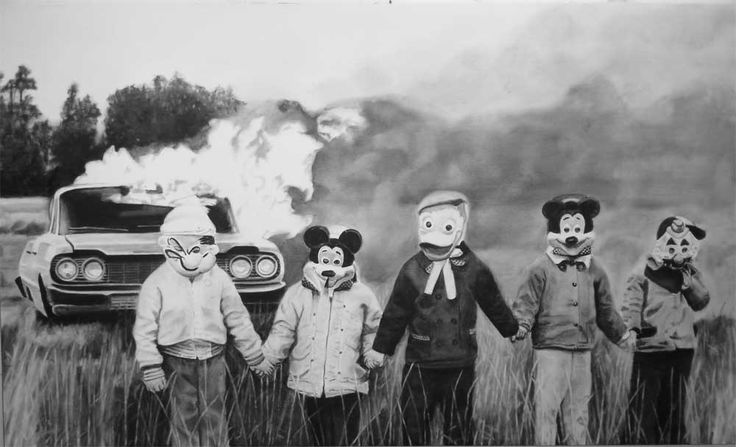

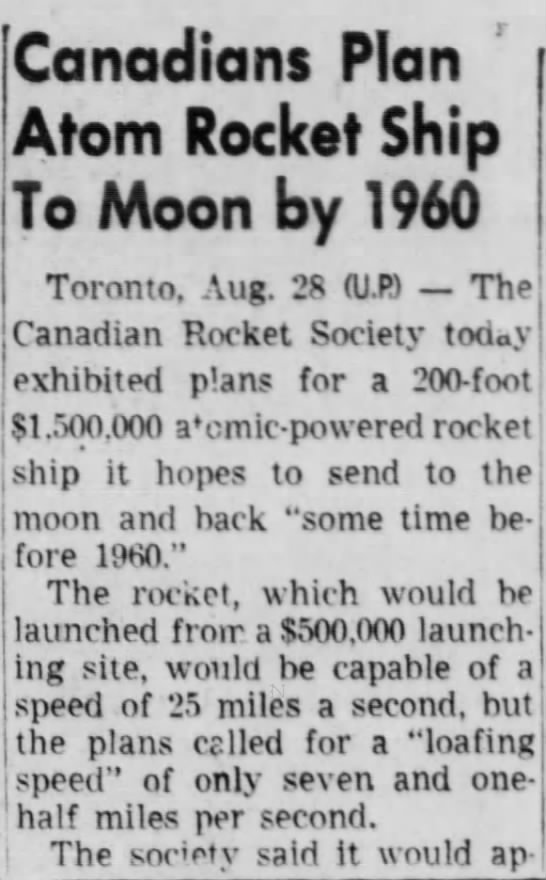

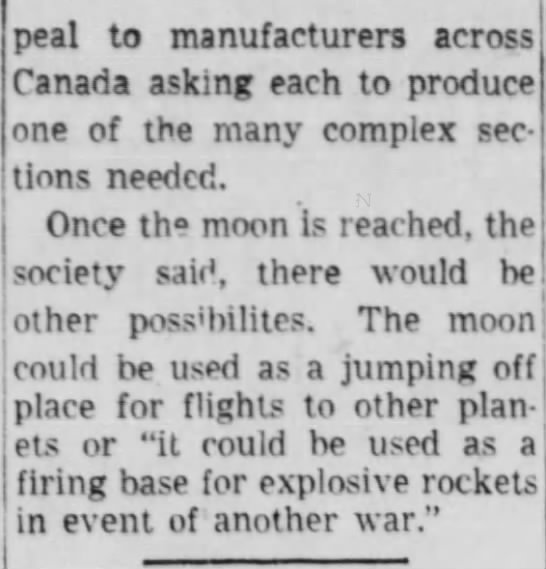

Giant leaps in technology provoke some to the extremes, with one group embracing the future too tightly and another balling up into a fetal position.

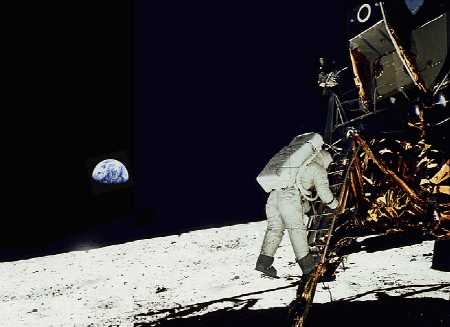

Case in point: In the same decade humans set foot on the moon, the most soaring technological achievement of our species, Sir Edmund Hillary went on an expedition to the Himalayas to search for the Abominable Snowman. There are still some among us all these years later who believe Yeti roams the Earth and the moonwalk was faked.

· · ·

As long as the Earth is around, they’ll be those who wrongly argue that it’s flat.

Few did so more vehemently than evangelist Wilbur Glenn Voliva, one of the most famous advocates of Flat Earth theories in America during the first half of the 20th century. In 1906, the preacher gained power over the Christian Catholic Apostolic Church in Zion, Illinois. He turned the community of 6,000 into a multi-pronged industrial concern, taking advantage of the very low wages he paid members of his flock. By the 1920s, Voliva owned one of the most powerful radio stations in the nation from which to preach his anti-science views, a forerunner of the many dicey religious figures to come who would mix mass and media.

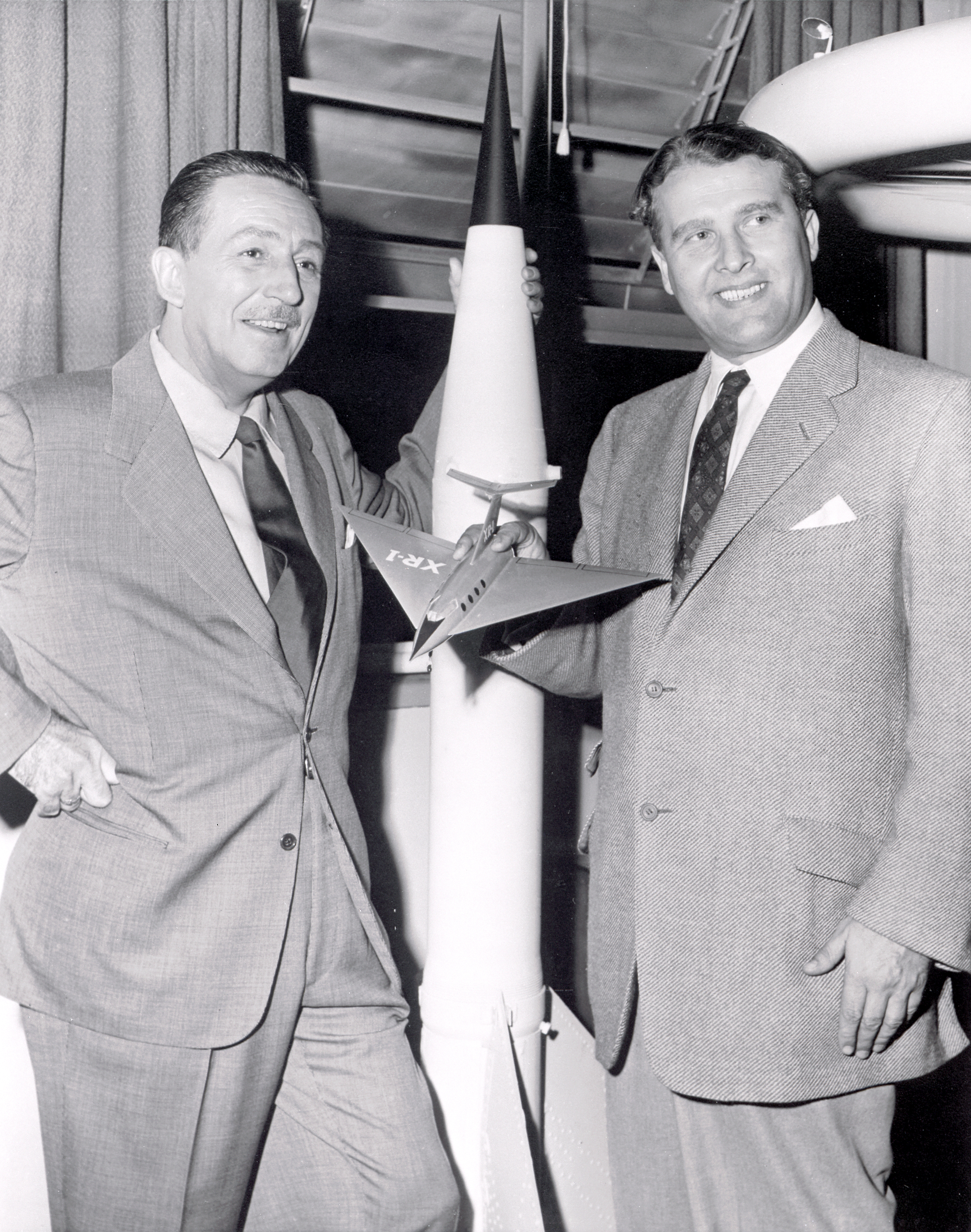

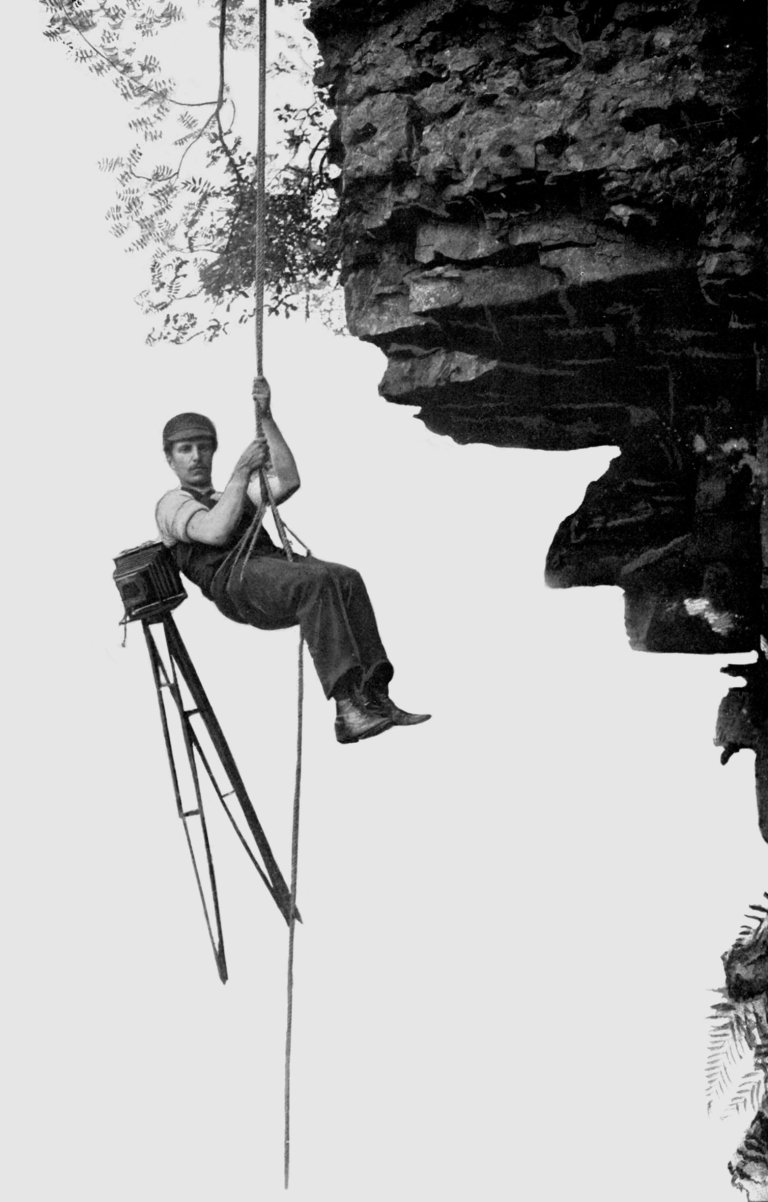

While Voliva despised globes, it was the advent of aerial photography that dimmed but did not end his career. After all, despite any proof, some still see what they want to see.

· · ·

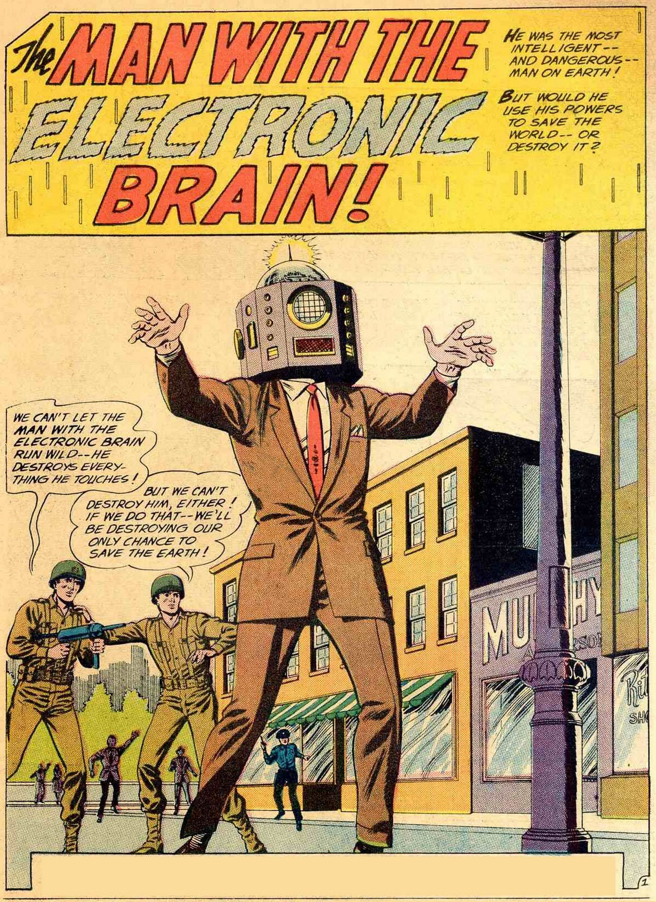

Many government jobs will likely be automated out of existence in the coming decades, but President?!

During the last American Presidential election, Transhumanist candidate Zoltan Istvan enthusiastically anticipated an age of techno-fascism, the complete removal of humans from politics in favor of an Artificial Intelligence dictator. He said this to BBC Future:

“I’ve advocated for an artificial intelligence to become president one day. If we had a truly altruistic entity that was after the best interests of society maybe giving up at least some freedoms would be beneficial if that was truly in our best interests. What’s happened in the past is we’ve had dictators who are selfish, and they’ve done an absolutely terrible job of running countries. But what if you actually had somebody who really was after your best interests, wouldn’t you want him on your team?”

Istvan envisions regular elections, in which “voters would decide on the robot’s priorities,” which isn’t very comforting in a country that saw nearly 63 million turn the lever for Donald Trump.

· · ·

Two excerpts follow about this Digital Age divide, one about some recoiling from even common sense and a second piece about those rushing headlong into an algorithmic embrace.

The opening of Graham Ambrose’s Denver Post article “These Coloradans say Earth is flat. And gravity’s a hoax. Now, they’re being persecuted“:

Every Tuesday at 6 p.m., three dozen Coloradans from every corner of the state assemble in the windowless back room of a small Fort Collins coffee shop. They have met 16 times since March, most nights talking through the ins and outs of their shared faith until the owners kick them out at closing.

They have no leaders, no formal hierarchy and no enforced ideology, save a common quest for answers to questions about the stars. Their membership has slowly swelled in the past three years, though persecution and widespread public derision keep them mostly underground. Many use pseudonyms, or only give first names.

“They just do not want to talk about it for fear of reprisals or ridicule from co-workers,” says John Vnuk, the group’s founder who lives in Fort Collins.

He is at the epicenter of a budding movement, one that’s coming for your books, movies, God and mind. They’re thousands strong — perhaps one in every 500 — and have proponents at the highest levels of science, sports, journalism and arts.

They call themselves Flat Earthers. Because they believe Earth — the blue, majestic, spinning orb of life — is as flat as a table.

And they want you to know. Because it’s 2017.

“This is a new awakening,” Vnuk says with a spark in his earth-blue eyes. “Some will accept it, some won’t. But love it or hate it, you can’t ignore Flat Earth.”•

From Michael Linhorst’s Politico Magazine piece “Could a Robot Be President?“:

A small group of scientists and thinkers believes there could be an alternative, a way to save the president—and the rest of us—from him- or herself. As soon as technology advances far enough, they think we should put a computer in charge of the country. Yes, it sounds nuts. But the idea is that artificial intelligence could make America’s big, complicated decisions better than any person could, without the drama or shortsightedness that we grudgingly accept from our human presidents.

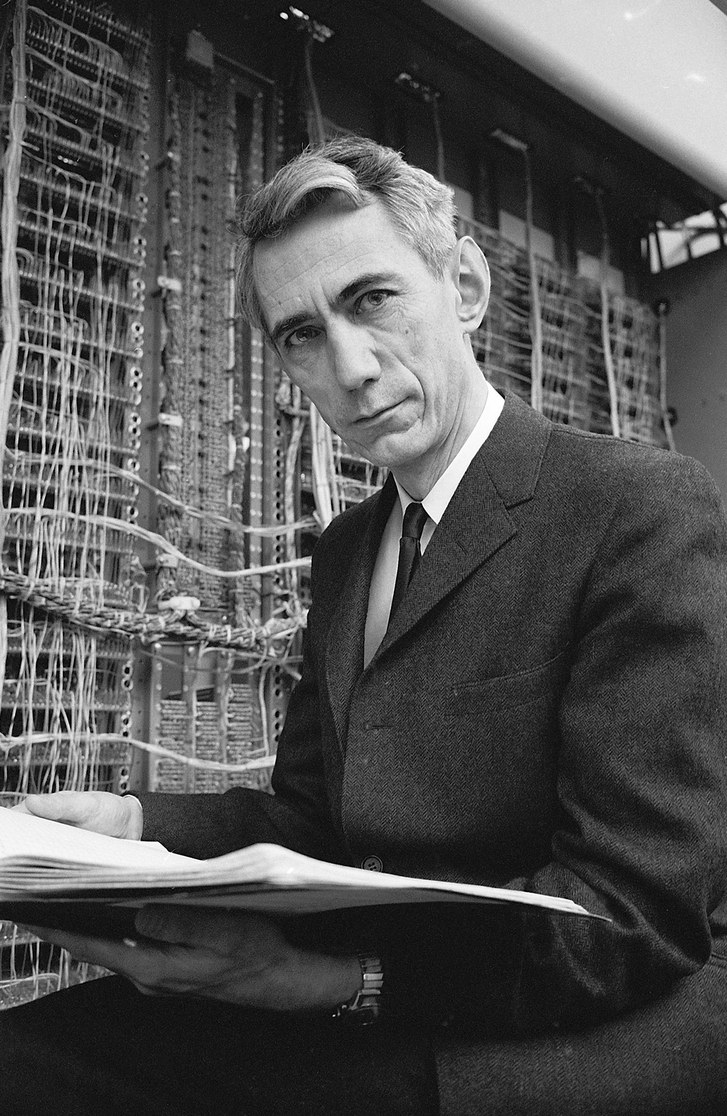

If you’re imagining a Terminator-style machine sitting behind the Resolute desk in the Oval Office, think again. The president would more likely be a computer in a closet somewhere, chugging away at solving our country’s toughest problems. Unlike a human, a robot could take into account vast amounts of data about the possible outcomes of a particular policy. It could foresee pitfalls that would escape a human mind and weigh the options more reliably than any person could—without individual impulses or biases coming into play. We could wind up with an executive branch that works harder, is more efficient and responds better to our needs than any we’ve ever seen.

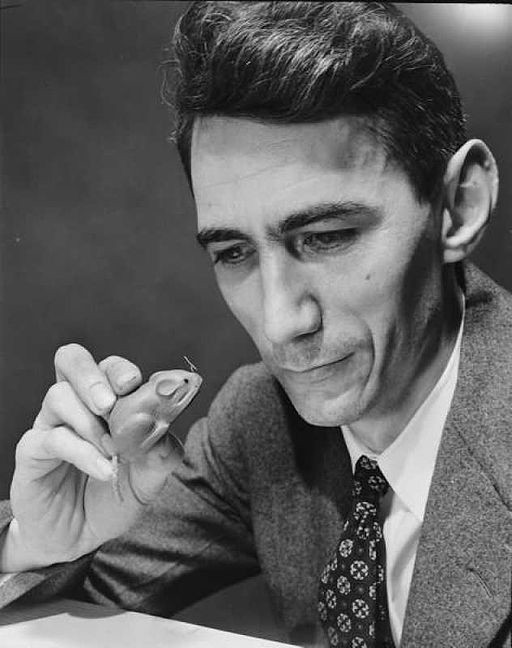

There’s not yet a well-defined or cohesive group pushing for a robot in the Oval Office—just a ragtag bunch of experts and theorists who think that futuristic technology will make for better leadership, and ultimately a better country. Mark Waser, for instance, a longtime artificial intelligence researcher who works for a think tank called the Digital Wisdom Institute, says that once we fix some key kinks in artificial intelligence, robots will make much better decisions than humans can. Natasha Vita-More, chairwoman of Humanity+, a nonprofit that “advocates the ethical use of technology to expand human capacities,” expects we’ll have a “posthuman” president someday—a leader who does not have a human body but exists in some other way, such as a human mind uploaded to a computer. Zoltan Istvan, who made a quixotic bid for the presidency last year as a “transhumanist,” with a platform based on a quest for human immortality, is another proponent of the robot presidency—and he really thinks it will happen.

“An A.I. president cannot be bought off by lobbyists,” he says. “It won’t be influenced by money or personal incentives or family incentives. It won’t be able to have the nepotism that we have right now in the White House. These are things that a machine wouldn’t do.”

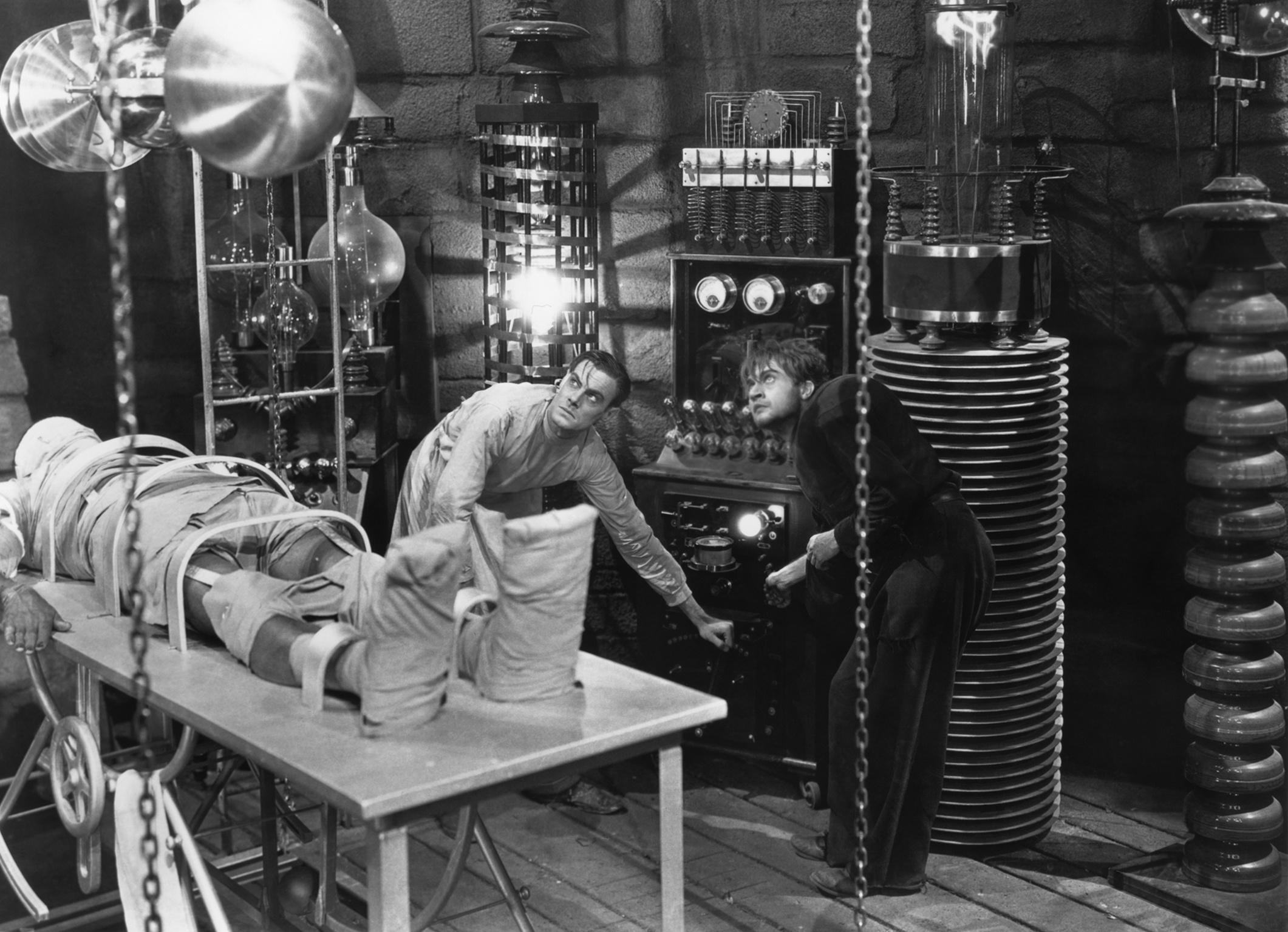

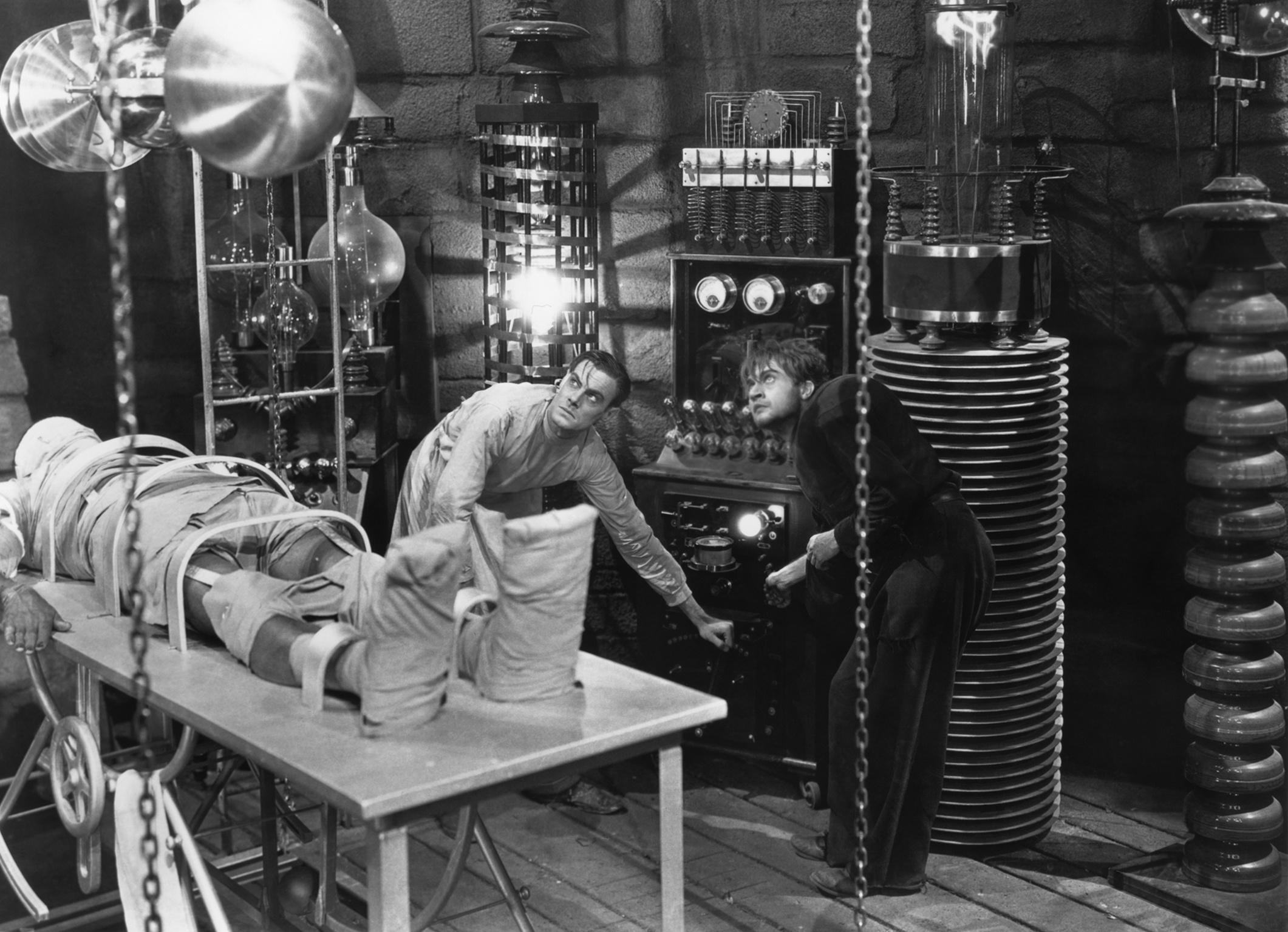

The idea of a robot ruler has been floating around in science fiction for decades. In 1950, Isaac Asimov’s short story collection I, Robot envisioned a world in which machines appeared to have consciousness and human-level intelligence. They were controlled by the “Three Laws of Robotics.” (First: “A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.”) Super-advanced A.I. machines in Iain Banks’ Culture series act as the government, figuring out how best to organize society and distribute resources. Pop culture—like, more recently, the movie Her—has been hoping for human-like machines for a long time.

But so far, anything close to a robot president was limited to those kinds of stories. Maybe not for much longer. In fact, true believers like Istvan say our computer leader could be here in less than 30 years.•