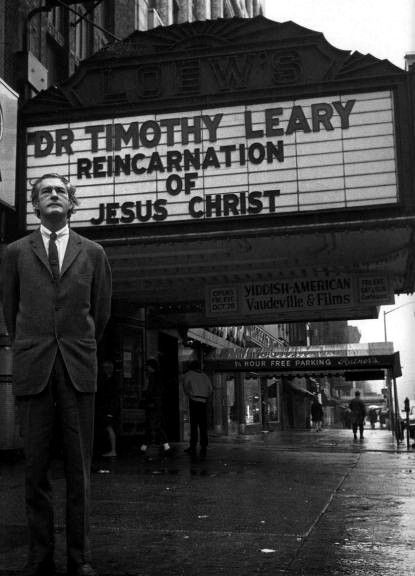

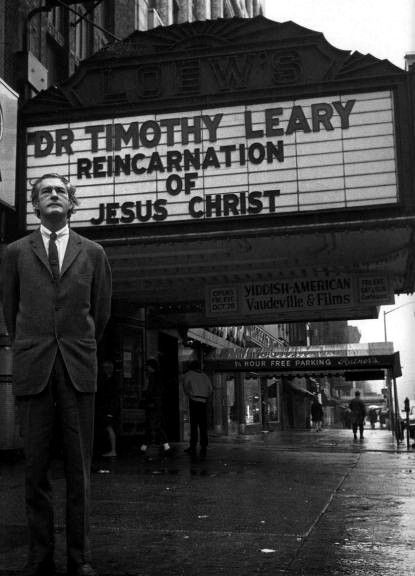

Two excerpts follow from 1960s Psychedelic Review articles about the drug culture of that era, penned by Timothy Leary and Stewart Brand.

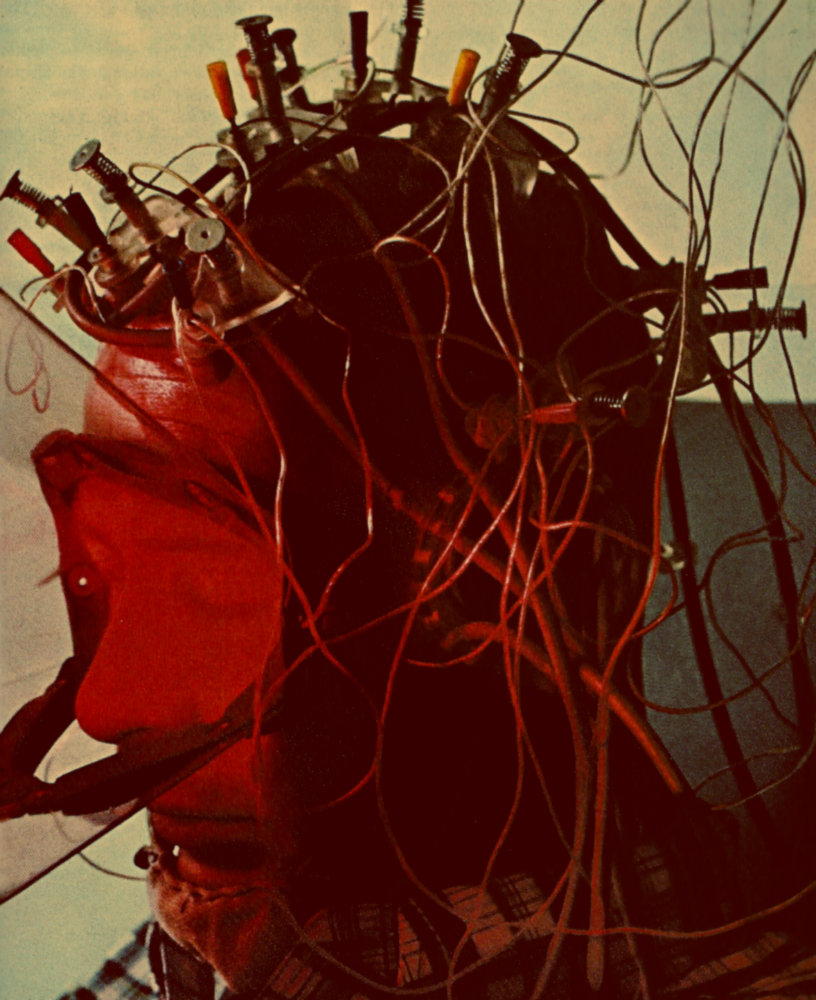

Before there was turnt, there was turned-on, the term for LSD experimentation taken from the Timothy Leary-Marshall McLuhan co-created mantra “Turn on, Tune in, Drop Out.” Thanks to some fakakta reasoning, Leary was allowed, during his Harvard professor days, to do acid tests on Massachusetts prison inmates, the belief being that the trip would help them arrive at rehabilitation. The subjects were wary of the good doctor, and for good reason, though by Leary’s telling everything went well overall. The guru recalled the experience in an article in the 1969 Psychedelic Review. An excerpt:

I’ll never forget that morning. After about half an hour, I could feel the effect coming up, the loosening of symbolic reality, the feeling of humming pressure and space voyage inside my head, the sharp, brilliant, brutal, intensification of all the senses. Every cell and every sense organ was humming with charged electricity. I felt terrible. What a place to be on a gray morning! In a dingy room, in a grim penitentiary, out of my mind. I looked over at the man next to me, a Polish embezzler from Worcester, Massachusetts. I could see him so clearly. I could see every pore in his face, every blemish, the hairs in his nose, the incredible green-yellow enamel of the decay in his teeth, the wet glistening of his frightened eyes. I could see every hair in his head, as though each was as big as an oak tree. What a confrontation! What am I doing here, out of my mind, with this strange mosaic-celled animal, prisoner, criminal?

I said to him, with a weak grin, How are you doing, John? He said, I feel fine. Then he paused for a minute, and asked, How are you doing, Doc? I was about to say in a reassuring psychological tone that I felt fine, but I couldn’t, so I said, I feel lousy. John drew back his purple pink lips, showed his green-yellow teeth in a sickly grin and said, What’s the matter, Doc? Why you feel lousy? I looked with my two microscopic retina lenses into his eyes. I could see every line, yellow spider webs, red network of veins gleaming out at me. I said, John, I’m afraid of you. His eyes got bigger, then he began to laugh. I could look inside his mouth, swollen red tissues, gums, tongue, throat. Well that’s funny Doc, ’cause I’m afraid of you. We were both smiling at this point, leaning forward. Doc, he said, why are you afraid of me? I said, I’m afraid of you, John, because you’re a criminal. I said, John, why are you afraid of me? He said, I’m afraid of you Doc because you’re a mad scientist. Then our retinas locked and I slid down into the tunnel of his eyes, and I could feel him walking around in my skull and we both began to laugh. And there it was, that dark moment of fear and distrust, which could have changed in a second to become hatred, terror. We’d made the love connection. The flicker in the dark. Suddenly, the sun came out in the room and I felt great and I knew he did too.

We had passed that moment of crisis, but as the minutes slowly ticked on, the grimness of our situation kept coming back in microscopic clarity. There were the four of us turned-on, every sense vibrating, pulsating with messages, two billion years of cellular wisdom, but what could we do trapped within the four walls of a gray hospital room, barred inside a maximum security prison? Then one of the great lessons in my psychedelic training took place. One of the four of us was a Negro from Texas, jazz saxophone player, heroin addict. He looked around with two huge balls of ocular white, shook his head, staggered over to the record player, put on a record. It was a Sonny Rollins record which he’d especially asked us to bring. Then he lay down on the cot and closed his eyes. The rest of us sat by the table while metal air from the yellow saxophone, spinning across copper electric wires, bounced off the wails of the room. There was a long silence. Then we heard Willy moaning softly, and moving restlessly on the couch. I turned and looked at him, and said, Willy, are you all right? There was apprehension in my voice. Everyone in the room swung their heads anxiously to look and listen for the answer. Willy lifted his head, gave a big grin, and said, Man, am I all right? I’m in heaven and I can’t believe it! Here I am in heaven man, and I’m stoned out of my mind, and I’m swinging like I’ve never before and it’s all happening in prison, and you ask me man, am I all right. What a laugh! And then he laughed, and we all laughed, and suddenly we were all high and happy and chuckling at what we had done, bringing music, and love, and beauty, and serenity, and fun, and the seed of life into that grim and dreary prison. …

As I rode along the highway, the tension and the drama of the day suddenly snapped off and I could look back and see what we had done. Nothing, you see, is secret in prison, and the eight of us who had assembled to take drugs together in a prison were under the gaze of every convict in the prison and every guard, and within hours the word would have fanned through the invisible network to every other prison in the state. Grim Walpole penitentiary. Grey, sullen-walled Norfolk.

Did you hear? Some Harvard professors gave a new drug to some guys at Concord. They had a ball. It was great. It’s a grand thing. It’s something new. Hope. Maybe. Hope. Perhaps. Something new. We sure need something new. Hope.•

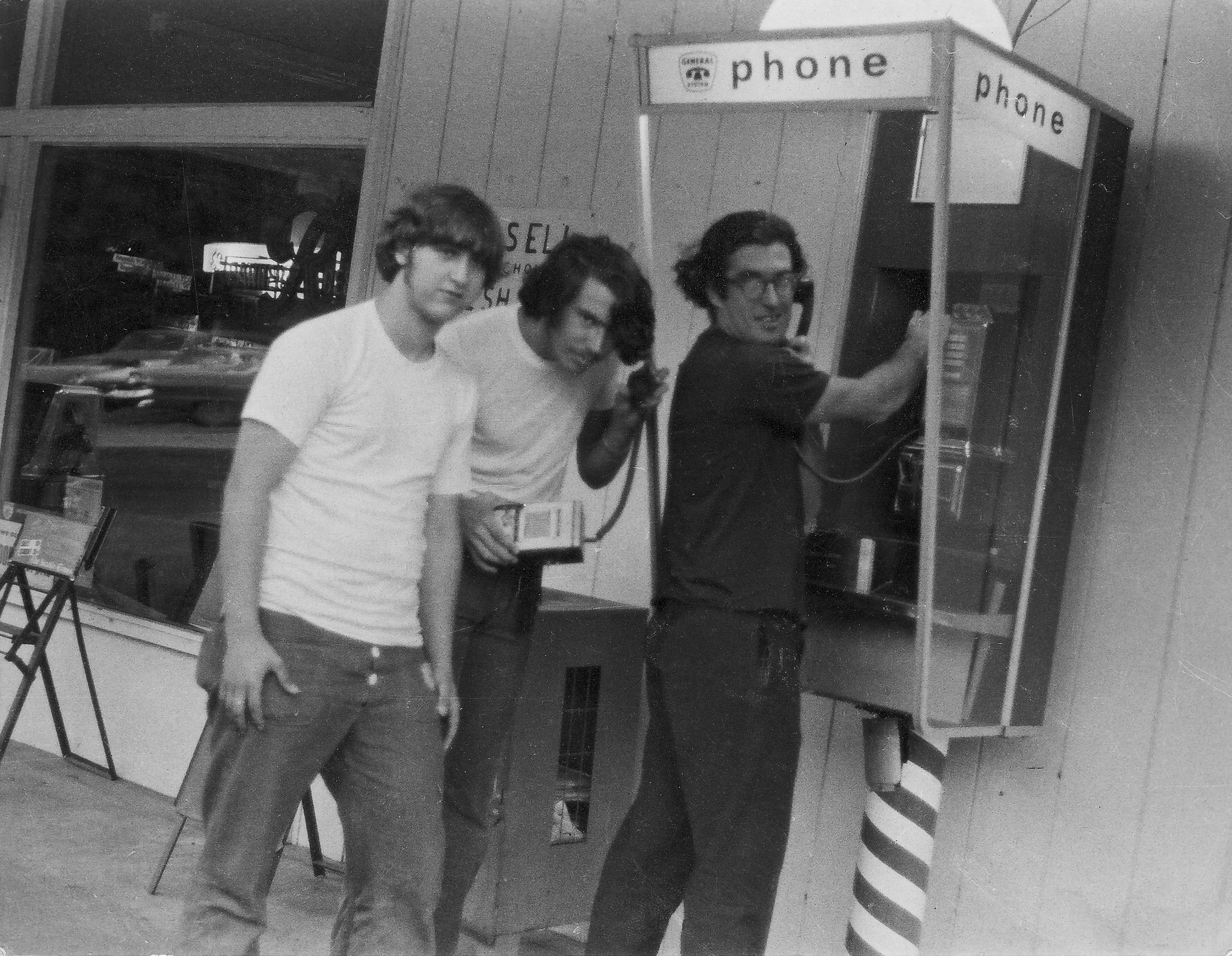

Peyote has historically been central to the Native American church meeting. In a 1967 Psychedelic Review article, Stewart Brand, Prankster and prophet, wrote of one such congregation he attended. An excerpt:

The meeting is mandala-form, a circle with a doorway to the east. The roadman will sit opposite the door, the moon-crescent altar in front of him. To his left sits the cedarman, to his right the drummer. On the right side as you enter will be the fireman. The people sit around the circle. In the middle is the fire.

A while after dark they go in. This may be formal, filling in clockwise around the circle in order. The roadman may pray outside beforehand, asking that the place and the people and the occasion be blessed.

Beginning a meeting is as conscious and routine as a space launch countdown. At this time the fireman is busy starting the fire and seeing that things and people are in their places. The cedarman drops a little powder of cedar needles and little balls, goes down the quickest. In all cases, the white fluff should be removed. There is usually a pot of peyote tea, kept near the fire, which is passed occasionally during the night. Each person takes as much medicine as he wants and can ask for more at any time. Four buttons is a common start. Women usually take less than the men. Children have only a little, unless they are sick.

Everything is happening briskly at this point. People swallow and pass the peyote with minimum fuss. The drummer and roadman go right into the starting song. The roadman, kneeling on one or both knees, begins it with the rattle in his right hand. The drummer picks up the quick beat, and the roadman gently begins the song. His left hand holds the staff, a feather fan, and some sage. He sings four times, ending each section with a steady quick rattle as a signal for the drummer to pause or re-wet the drumhead before resuming the beat. Using his thumb on the drumhead, the drummer adjusts the beat of his song. When the roadman finishes he passes the staff, gourd, fan and sage to the cedarman, who sings four times with the random drumming. So it goes, the drum following the staff to the left around the circle, so each man sings and drums many times during the night.•