In the post about Olivetti, I mentioned the Austrian-born design genius Ettore Sottsass, who passed away in 2007. Here’s a piece from his best-known essay, “When I Was a Very Small Boy“:

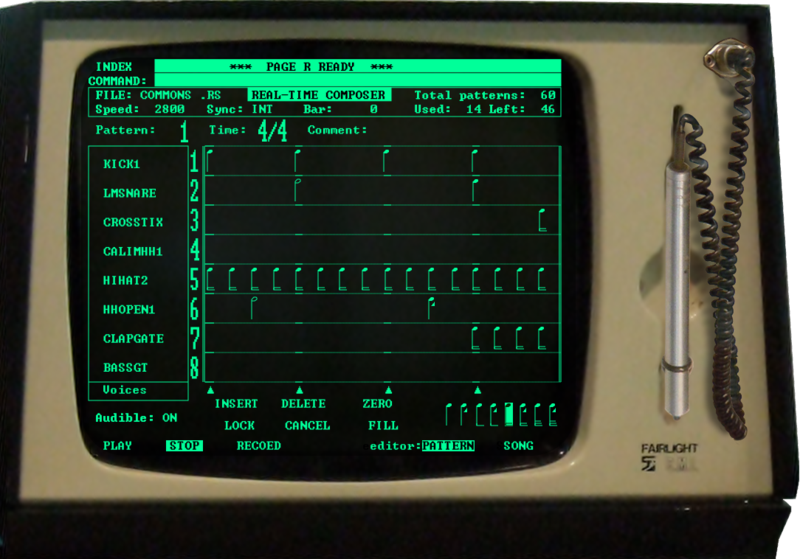

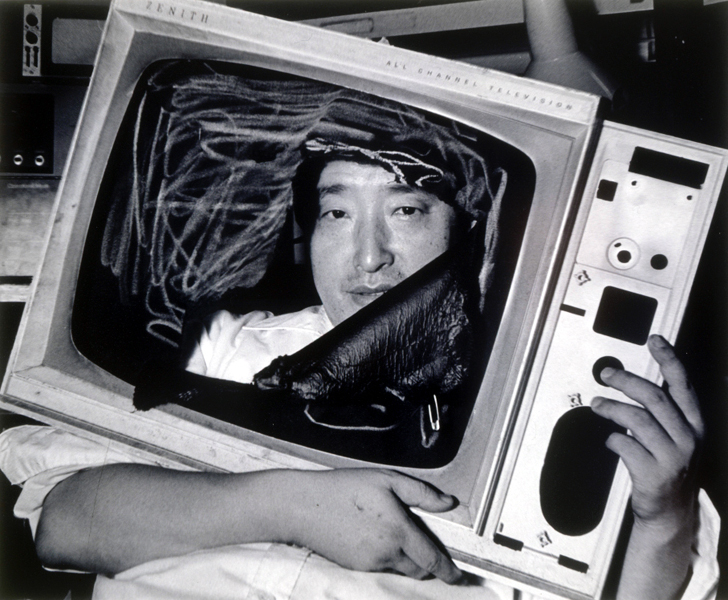

“Now that I’m old they let me design electronic machines and other machines in iron, with flashing phosphorescent lights and sounds and no one knows whether they are cynical or ironical: now they only let me design furniture that ought to be sold, furniture they say, that is useful to society, they say, and other things that are sold ‘at low prices’ they say, and in this way they can sell more of them, for society they say, and now I design things of this kind. Now they pay me to design them. Not much, but they pay me. Now they look for me and wait for models from me, as they say, ideas and solutions which end up heaven knows where.

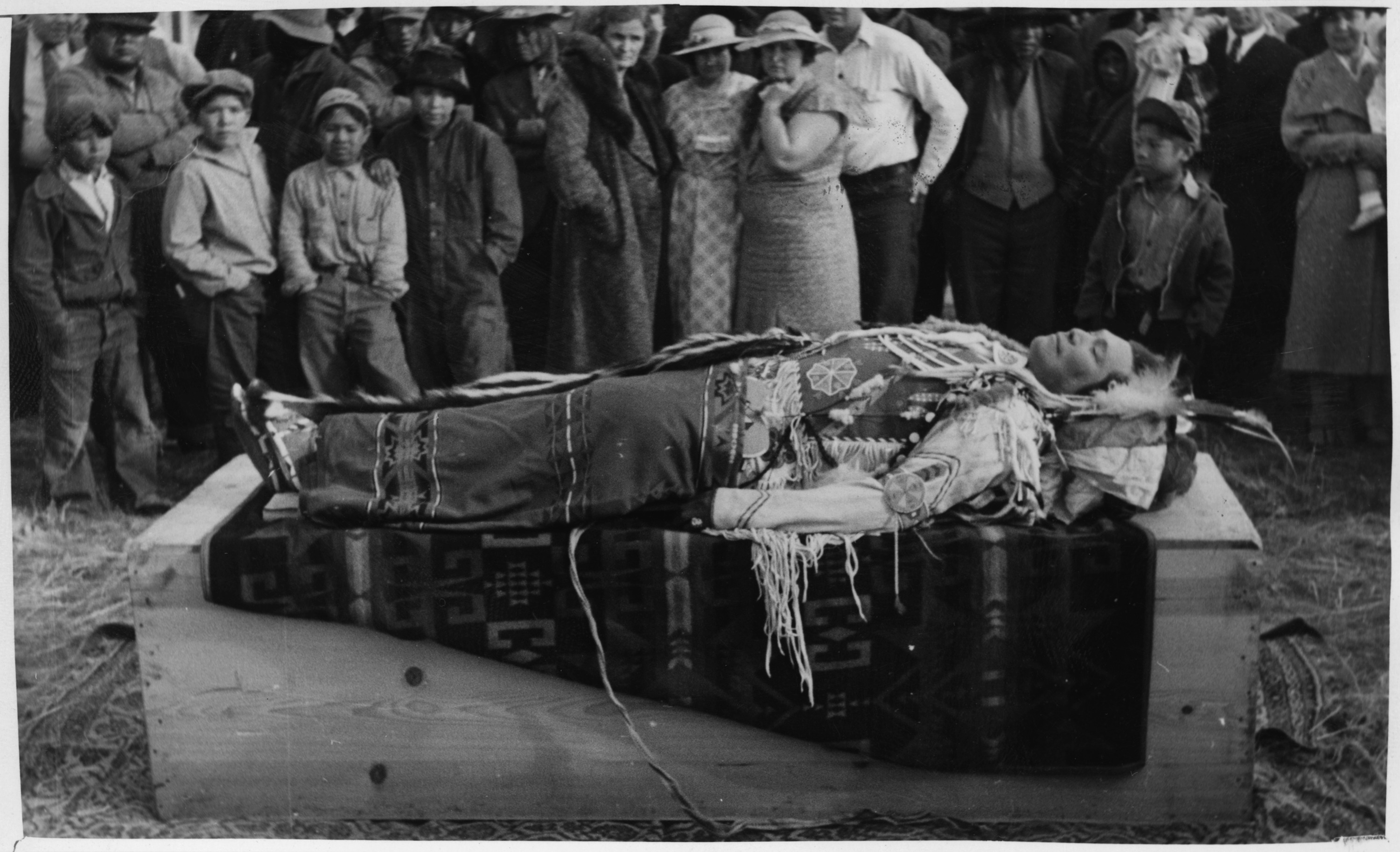

Now everything seems to have changed. The things I do (by myself or with my companions) seem to have changed and the way they are done also seems to have changed because, goodbye bright blue Planet, goodbye melodious seasons, goodbye stones, dust, leaves, ponds, and dragon flies, goodbye boiling-hot days, dead dogs by the roadside, shadows in the wood like prehistoric dragons, goodbye Planet, by now I feel as if I do the things I do sitting in a bunker of damp artificial light and conditioned air, sitting at this white laminate table, sitting in this silver plastic chair, captain of a spaceship traveling at thousands of miles an hour, squashed against this seat — immobile in the sky.

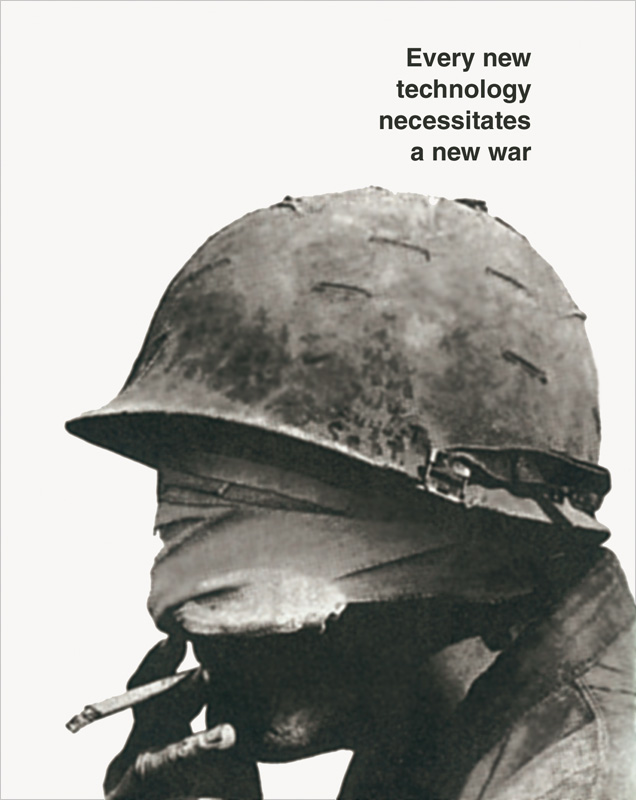

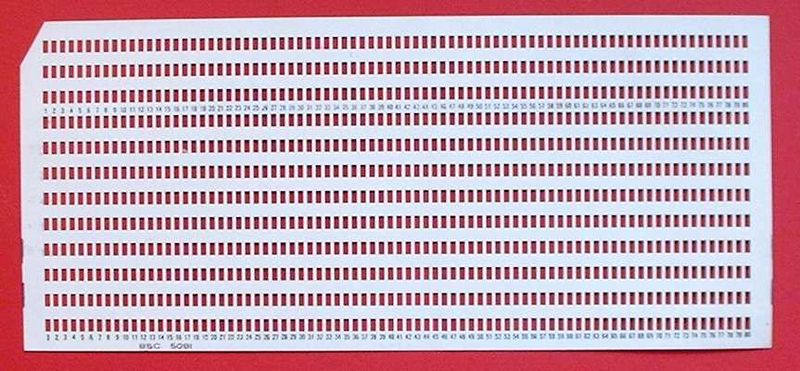

By now I have to think of things from an artificial space, with neither place nor time; a space only of words, phone-calls, meetings, timetables, politics, waiting, failures. By now I’m a professional acrobat, actor and tightrope walker, for an audience that I invent, that I describe to myself, a remote audience with whom I have no contact, stifled echoes of whose talking, clapping and disapproval reach me, whose wars, catastrophes, famines, suicides, escapes, poverty or anxious restings along crowded beaches or inside smoky stadiums I read about in papers; how can I know who are the ones expecting something from me?

I would like to break this strange mechanism I’ve been driven into.”