There are enough real monsters in the world, but we invent more, projecting our fears and loathing onto others, hoping to destroy these feelings, to be rid of them. And this act of projection itself often leads to monstrous results. In the 1800s, the bloody coughs of tuberculosis so frightened people that a parasitic creature was roused from his daytime slumber. From Abigail Tucker’s Smithsonian article “The Great New England Vampire Panic,” a passage about a New Hampshire family that succumbed to the dreaded illness one member after another:

“People dreaded the disease without understanding it. Though Robert Koch had identified the tuberculosis bacterium in 1882, news of the discovery did not penetrate rural areas for some time, and even if it had, drug treatments wouldn’t become available until the 1940s. The year Lena died, one physician blamed tuberculosis on ‘drunkenness, and want among the poor.’ Nineteenth-century cures included drinking brown sugar dissolved in water and frequent horseback riding. ‘If they were being honest,’ Bell says, ‘the medical establishment would have said, ‘There’s nothing we can do, and it’s in the hands of God.’’

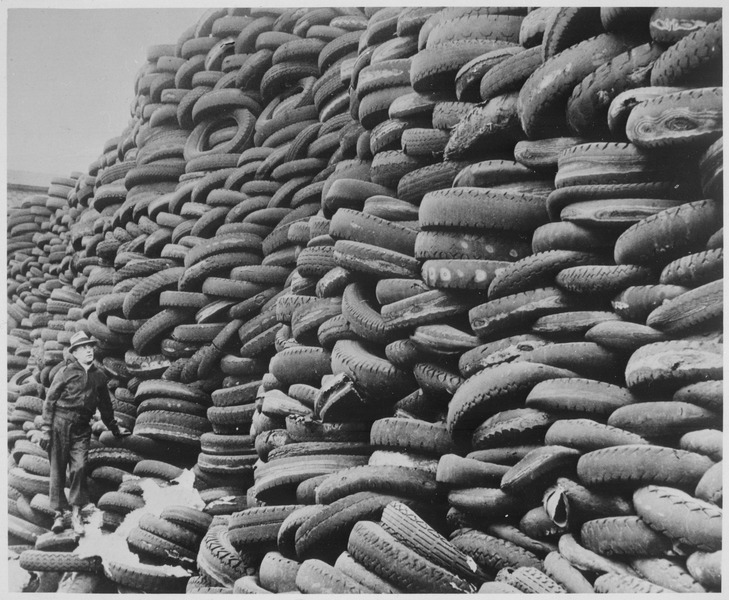

The Brown family, living on the eastern edge of town, probably on a modest homestead of 30 or 40 stony acres, began to succumb to the disease in December 1882. Lena’s mother, Mary Eliza, was the first. Lena’s sister, Mary Olive, a 20-year-old dressmaker, died the next year. A tender obituary from a local newspaper hints at what she endured: ‘The last few hours she lived was of great suffering, yet her faith was firm and she was ready for the change.’ The whole town turned out for her funeral, and sang ‘One Sweetly Solemn Thought,’ a hymn that Mary Olive herself had selected.

Within a few years, Lena’s brother Edwin—a store clerk whom one newspaper columnist described as ‘a big, husky young man’—sickened too, and left for Colorado Springs hoping that the climate would improve his health.

Lena, who was just a child when her mother and sister died, didn’t fall ill until nearly a decade after they were buried. Her tuberculosis was the ‘galloping’ kind, which meant that she might have been infected but remained asymptomatic for years, only to fade fast after showing the first signs of the disease. A doctor attended her in ‘her last illness,’ a newspaper said, and ‘informed her father that further medical aid was useless.’ Her January 1892 obituary was much terser than her sister’s: ‘Miss Lena Brown, who has been suffering from consumption, died Sunday morning.’

As Lena was on her deathbed, her brother was, after a brief remission, taking a turn for the worse. Edwin had returned to Exeter from the Colorado resorts ‘in a dying condition,’ according to one account. ‘If the good wishes and prayers of his many friends could be realized, friend Eddie would speedily be restored to perfect health,’ another newspaper wrote.

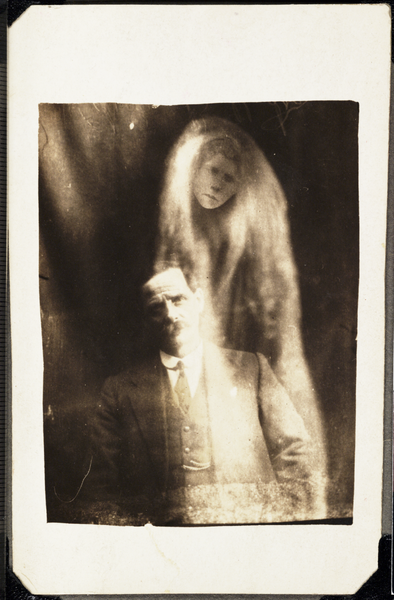

But some neighbors, likely fearful for their own health, weren’t content with prayers. Several approached George Brown, the children’s father, and offered an alternative take on the recent tragedies: Perhaps an unseen diabolical force was preying on his family. It could be that one of the three Brown women wasn’t dead after all, instead secretly feasting ‘on the living tissue and blood of Edwin,’ as the Providence Journal later summarized. If the offending corpse—the Journal uses the term ‘vampire’ in some stories but the locals seemed not to—was discovered and destroyed, then Edwin would recover. The neighbors asked to exhume the bodies, in order to check for fresh blood in their hearts.”