Since the start of the Tea Party paranoia about the U.S. government’s supposed “hostile takeover” of the citizenry and the free markets, I’ve argued that despite some real assaults on individual rights (e.g., Patriotic Act-enabled surveillance), control by any central body in even a nominal democracy is on the wane. Big Brother isn’t as much a problem as is just keeping the family together at all.

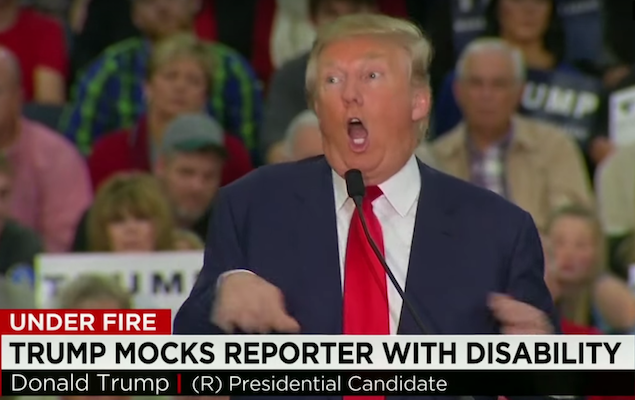

That being said, I think Yuval Noah Harari (whose latest book, Homo Deus, will hopefully arrive in my mailbox this week) overplays his hand a bit on this point in what’s otherwise a fun and provocative New Yorker essay about our technologically advanced society inexplicably enabling Trump’s “nihilistic burlesque.” The historian offers a macro analysis of what ails disgruntled America (and much of the rest of the world), assigning the disquiet to the fecklessness of our elected governments.

In America, we certainly have structural problems in ensuring the people are truly represented. The chief flaw, more than even Citizens United, is probably gerrymandering, which is why President Obama, in his first post-White House act, is joining forces with former Attorney General Eric Holder to legally challenge districting that runs afoul of common sense and, perhaps, the law. It’s a serious bug but not a fatal error.

Policy can be a brutally slow game, not nearly as fleet as a tweet, but it’s also not so fleeting. Today’s ballooning high school graduation rates required a change in priorities six years ago, The substantial gains in income for middle class and impoverished households in 2015 was the cumulative effect of the policies of a President determined to reverse course on Reaganomics, one who aimed to be a transformative instead of transitional leader. Going forward, automation is poised to threaten Labor in a large-scale manner, but for now the pendulum has swung in the direction of working people.

Harari is certainly correct in saying that technological tools have quickly outpaced our capacity to legislate them or to process them in an ethical fashion, and that could make war among nations or within them more likely. Off-the-shelf drones can now deliver explosions as well as pizzas. Tools like those will only get better (and worse).

Nothing speaks to the disruption of traditional governance as we’ve known it like Silicon Valley billionaires engaging in Space Race 2.0 against entire nations. Even if those dreams are still beyond reach for individuals with lots of stock options, they aren’t so far that they can be dismissed.

Individuals and corporations, however, work toward satisfying their own priorities, not always the greater good. Government, run reasonably well, should always be striving to accomplish the latter. As long as it does so to a fair degree, central authority will always have a role in our lives, no matter how fractured they become.

When some say philosophy is dead, seemingly giddy about it, I’m perplexed. We need it now more than ever. The same goes for government. It’s possible our great expectations may cause us to ignore real progress, but that will be a failing of “us,” not “them.”

From Harari:

Disruptive technologies pose a particularly acute threat to the power of national governments and ordinary citizens. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, progress in the form of the Industrial Revolution produced concomitant horrors, from the Dickensian coal pits to Congo’s rubber plantations and China’s disastrous Great Leap Forward. It took tremendous effort for politicians and citizens to put the train of progress on more benign tracks. Yet while the rhythm of politics has not changed much since the days of steam, technology has switched from first gear to fourth. Technological revolutions now vastly outpace political processes.

The Internet suggests how this happens. The Web is now crucial to our lives, economy, and security, yet the early, critical choices about its design and basic features weren’t made through a democratic political process—did you ever vote about the shape of cyberspace? Decisions made by Web designers years ago mean that today the Internet is a free and lawless zone that erodes state sovereignty, ignores borders, revolutionizes the job market, smashes privacy, and poses a formidable global-security risk. Governments and civic organizations conduct intense debates about restructuring the Internet, but the governmental tortoise cannot keep up with the technological hare.

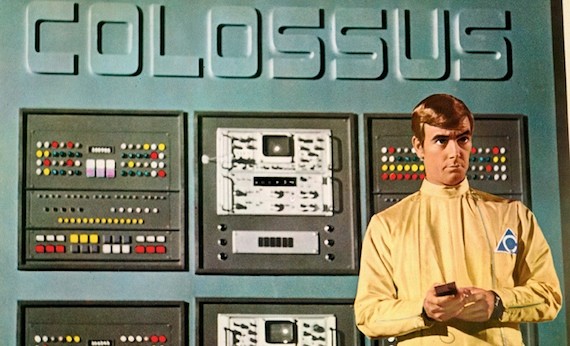

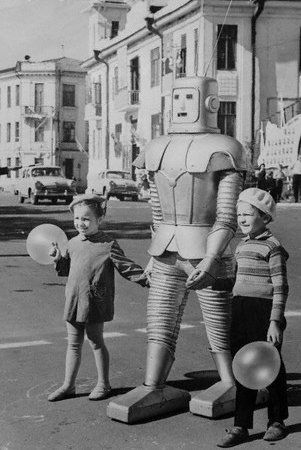

In the coming decades, we will likely see more Internet-like revolutions, in which technology steals up silently on politics. Artificial intelligence and biotechnology could overhaul not just societies and economies but our very bodies and minds. Yet these topics are hardly a blip in the current Presidential race. (In the first Clinton-Trump debate, the main reference to disruptive technology concerned Clinton’s e-mail debacle, and despite all the talk about job losses, neither candidate addressed the potential impact of automation.)

Ordinary voters may not understand artificial intelligence but they can sense that the democratic mechanism no longer empowers them.•