“In the formation of his brain, Rulloff was a ferocious animal.”

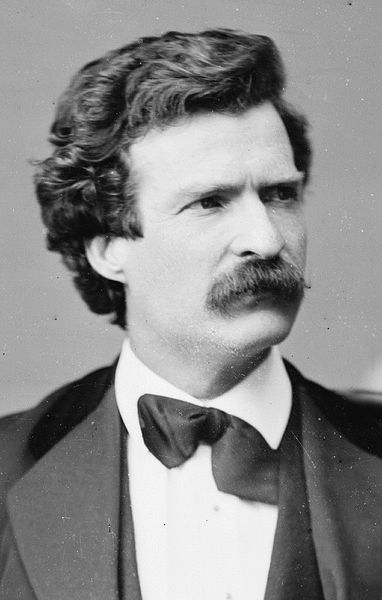

Even if he hadn’t had a brain the size of a medicine ball, Edward H. Rulloff’s death by execution would have been notable. A brilliant philologist and author who committed a slew of violent crimes during his life, Rulloff was the last prisoner to die by public hanging in New York State. For a long while, he managed to stay a step ahead of the law, even when he was suspected for the beating deaths of his wife and daughter and lethally poisoning a couple of other relatives. But when the vicious linguist was finally convicted to die for the murder of an Upstate New York shop clerk, some voiced support for sparing his life, in order to allow him to keep sharing his genius about language. Mark Twain coolly mocked them, suggesting, in Swiftian fashion, that someone else be hung in Rulloff’s place. The doomed man just wanted the show to get on the road. “Hurry it up!’ he hollered on the day he was to wear a noose, “I want to be in hell in time for dinner.”

Colorful enough, sure, but when his severed head was examined after the death sentence was carried out, Rulloff proved to have one of the largest brains ever recorded. From the May 24, 1871 New York Times article about the measure of a wonderful, terrible man:

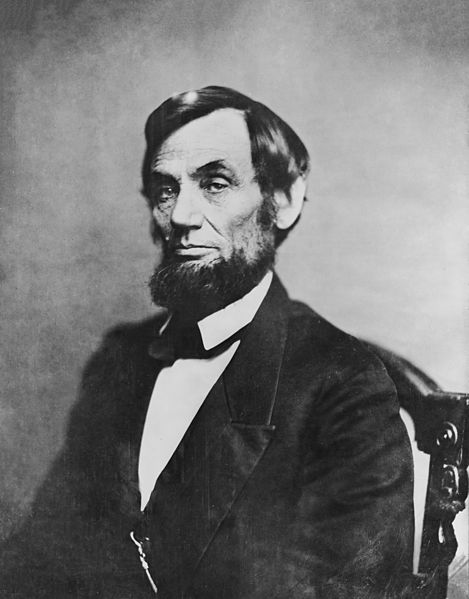

“The work of dissecting Rulloff’s head was so far completed this morning as to enable those having it in charge to ascertain the weight of his brain. The brain weighed fifty-nine ounces, being nine and a half or ten ounces heavier than the average weight. The heaviest brain ever weighed was that of Cuvier, the French naturalist, which is given by some authorities at sixty-five ounces. The brain of Daniel Webster (partly estimated on account of a portion being destroyed by disease) weighed sixty-four ounces. The brain of Dr. Abercrombie, of Scotland, weighed sixty-three ounces.

The average weight of men’s brain is about 50 ounces; the maximum weight 65 ounces (Cuvier’s), and the minimum weight (idiots) 20 ounces. As an average, the lower portion of the brain (cerebellum) is to the upper portion (cerebrum) as 1 is to 8 8-10. The lower, brute portion, of Rulloff’s brain and the mechanical powers were unusually large. The upper portion of the brain, which directs the higher moral and religious sentiments, was very deficient in Rulloff. In the formation of his brain, Rulloff was a ferocious animal, and so far as disposition could relieve him from responsibility, he was not strictly responsible for his acts. There is no doubt he thought himself not a very bad man, on the morning he was lead out of prison, cursing from the cell to the gallows.

“He was not strictly responsible for his acts.”

With the protection of a skull half an inch thick, and a scalp of the thickness and toughness of a rhinoceros rind, the man of seven murders was provided with a natural helmet that would have defied the force of any pistol bullet. If he had been in Mirick’s place the bullet would have made only a slight wound; and had he been provided with a cutis vera equal to his scalp, his defensive armor against bullets would have been as complete as a coat of mail.

The cords in Rulloff’s neck were as heavy and strong as those of an ox, and from his formation, one would almost suppose that he was protected against death from the gallows as well as by injury to his head.

Rulloff’s body was [said to be] larger than it was supposed to be by casual observers. The Sheriff ascertained when he took measure of the prisoner for a coffin to bury him in, that he was five feet and ten inches in height, and measured nineteen inches across the shoulders. When in good condition his weight was about 175 pounds.

It is very well-known that Rulloff’s grave was opened three times last Friday night by different parties who wanted to obtain his head. One of those parties was from Albany, and twice the body was disinterred by persons living in Binghamton. One company would no sooner cover up the body, which all found headless, and leave it, then another company would come and go through with the same operations. It is now known that the head was never buried with the body, but was legally obtained before the burial by the surgeons who have possession of it.

The hair and beard were shaved off close, and an excellent impression in plaster was taken of the whole head. The brain is now undergoing a hardening process, and when that is completed an impression will be taken of it entire, and then it will be parted, the different parts weighed, and impressions made of the several sections.”