I was disappointed when I first played the new EconTalk podcast, which featured host Russ Roberts interviewing Capital in the Twenty-First Century author Thomas Piketty; I simply couldn’t understand the guest due to his French accent (or my American ears). Thankfully, the program is transcripted, and it makes for a fascinating read. The Libertarian host and his politically opposed guest go at it in an intelligent way on all matters of wealth creation and distribution.

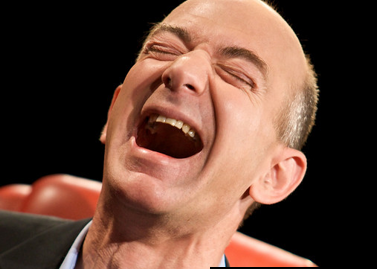

One argument that Roberts makes always galls me because I think it’s intellectually dishonest: He says that really innovative people (e.g., Steve Jobs and Bill Gates) deserve the huge money they make, implying that most of the wealth in the country is concentrated with such people. That’s not so. They’re outliers, extreme exceptions being raised to argue a rule.

There are also the Carly Fiorinas of the world, who run formerly great companies like Hewlett-Packard into the ground and make a soft landing with a ginormous golden parachute just before thousands of workers are laid off. If you want to say she’s equally an outlier, feel free, but the majority of CEOs in the U.S. aren’t great innovators. They’re stewards being compensated like innovators, collecting generous “royalties” on someone else’s ideas.

One excerpt from the show on this topic:

“Russ Roberts:

I’m just trying to get at the mechanics, because I think it matters a lot for why inequality has risen. So, for example, if somebody has gotten wealthy because they’ve been able to be bailed out using my tax dollars, then I would resent that. But if somebody is wealthy because they’ve created something marvelous, then Idon’t resent it. And my argument is that when we look at the Forbes 400, or the top 1%, many of the people in their, their incomes, their wealth has risen at a greater rate than the economy as a whole not because they are exploiting people, not because of corporate governance, but because of an increase in globalization that allows people to capture–make more people happy. Make more people–provide more value. My favorite example is sports. Lionel Messi makes about 3 times–the great soccer player, the great footballer, makes about 3 times what Pele made in his best earning years, 40 years ago. That’s not because Messi is a better soccer player. He’s not. Pele, I think, is probably a better soccer player. But Messi reaches more people, because of the Internet, because of technology and globalization. You can still argue that he doesn’t need $65 million a year and you should tax him at high tax rates. But I think as economists we should be careful about what the causal mechanism is. It matters a lot.

Thomas Piketty:

Oh, yes, yes, yes. But this is why my book is long, because I talk a lot about this mechanism. And I talk a lot about the entrepreneur, and the reason there is a lot of entrepreneurial wealth around, but my point is certainly not to deny this. My point is twofold. First, even if it was 100% entrepreneurial wealth, you don’t want to have the top growing 4 times faster than the average, even if it was complete mobility from one year to the other, you know, it cannot continue forever, otherwise the share of middle class in national wealth goes to 0% and you know, 0% is really very small. So that would be too much. And point number 2, is that when you actually look at the dynamics of top wealth holders, you know it’s really a mixture of, you know, you have entrepreneurs but you also have sons of entrepreneurs; you also have ex-entrepreneurs who don’t work any more but their wealth is rising as fast and sometimes faster than when they were actually working. You have–it’s a very complicated dynamics. And also be careful actually with Forbes’s ranking, which probably are even underestimating the rise of top wealth holders and you know, there are a lot of problems counting for inherited diversified portfolios. It’s a lot easier to spot people who have created their own company and who actually want to be in the ranking because usually they are quite proud of it, and maybe rightly so, than to spot the people, you know, who just inherited from the wealth. And so I think this data source is very biased in the direction of entrepreneurial wealth. But even if you take it as perfect data you will see that you have a lot of inherited wealth. You know, look: I give this example in the book, which is quite striking. The richest person in France and actually one of the richest in Europe, is Liliane Bettencourt. Actually, her father was a great entrepreneur. Eugene Schueller founded L’Oreal, number 1 cosmetics in the world, with lots of fancy products to have nice hair; this is very useful, this has improved the world welfare by a lot.

Russ Roberts:

Pleasant. It’s nice.

Thomas Piketty:

The only problem is that Eugene Schueller created L’Oreal in 1909. And he died in the 1950s, and you know, she has never worked. What’s interesting is that her fortune, between the [?], between 1990 and 2010, has increased exactly as much as the one of Bill Gates. She has gone from $5 to $30 billion, when Bill Gates has gone from like $10 to $60. It’sexactly in the same proportion. And you know, in a way, this is sad. Because of course we would all love Bill Gates’ wealth to increase faster than that of Liliane. Look, why would I–I’m not trying to–I’m just trying to look at the data. And when you look at the data, you would see that the dynamics of wealth that you mention are not only about entrepreneurs and merit, and it’s always a complicated mixture. You have oligarchs who are seated on a big pile of oil, which you know, I don’t know how much of it is their labor and talent but some of it is certainly direct appropriation. And once they are seated on this pile of wealth, the rate of return that they are getting by paying tons of people to make the right investment with their portfolio can be quite impressive. So I think we need to look at these dynamics in an open manner. And when Warren Buffet says, I should not be paying less tax than my secretary, I think he has a valid point. And I think the issue, the idea that we are going to solve this problem only by letting these people decide how much they want to give individually is a bit naive. I believe a lot in charitable giving, but I think we also need collective rules and laws in order to determine how each one of us is contributing to tax revenue and the common good.

Russ Roberts:

Well, the share contributed by the wealthy in the United States is relatively high. You could argue it should be higher. As you would point out, I don’t really have a model to know what that would be. But real question for me is the size of government. If there’s a reason for it to be larger, if money can be spent better by the government, that would be one thing. And again, the other question is what should be the ideal distribution of the tax burden.”